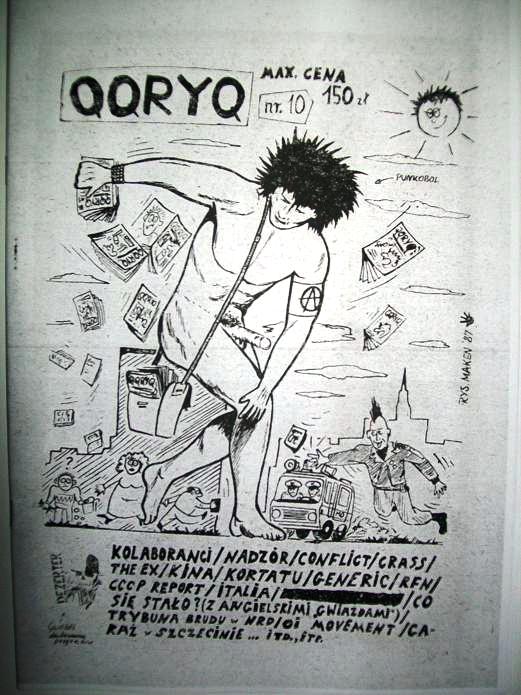

The majority of the editions of ‘QQRYQ’ was printed on Xerox from one hundred to two hundred copies. The matrices were made by hand, in a collage technique, from scraps of official newspapers and magazines, small text lines prepared on typewriter, hand written articles, photos, graphics, and comics. The first issue published on the offset appeared in 1990. It was also the first issue prepared with a usage of a computer. Against this background of Xerox and offset techniques of printing, the tenth edition of ‘QQRYQ’ seems to be very original. This edition was published by screen print, which was hardly ever practiced as a way of bringing out punk fanzines. The screen printing technique was extremely labour-intensive and took a lot of time to print even a relatively small number of copies. Another unusual fact about the tenth number of ‘QQRYQ’ was a usage of the official foolscap because of lack of different kinds of paper. The content of the issue did not vary so much from the rest of the editions, but worth mentioning were the graphics by Mirosław ‘Maken’ Dzięciołowski, reggae DJ, promoter, and alternative scene activist in the late 1980s in Poland. Dzięciołowski was one of a few regular contributors of ‘QQRYQ’.

During the first half of 1987, personal and ideological tensions within the MWU were rampant. These tensions came to a head early in the year, when the long-serving Chairman of the MWU, Pavel Boțu, committed suicide. This tragic event reflected not only the unprecedented degree of personal animosities and rivalries among the writers, but also a sharpening ideological divide along national-cultural lines. The Writers’ Conference organised on 18 May 1987 became the stage for heated and acrimonious debates. These debates reflected not only a generational rupture between the “generation of the 1960s” and the writers born in the interwar period, but also the radically changed ideological circumstances during Perestroika. Some members of the MWU did not hide their open dissatisfaction with the organisation’s leaders and used the context of Perestroika to voice radical demands. Aside from the journalist and publicist Valentin Mândâcanu’s incisive speech on the “language issue,” the speech made by Grigore Vieru attracted widespread attention due to its virulence and radicalism. At the time, Vieru was a well-known poet and author of children’s books, whose texts reached a wider audience compared to most of his colleagues. Vieru was frequently attacked for “nationalism” and “ideological deviations” by the MWU’s “old guard,” most notably Andrei Lupan. Vieru thus used the conference to mount a violent attack on Lupan personally and on the “old style of leadership” within the MWU more generally. However, Vieru’s speech is notable not because of the settling of personal scores, but due to the wider issues it raised. First, he responded to the accusations of emulating and “aping” the Romanian model by “looking beyond the Prut.” He rhetorically wondered: “Why wouldn’t I look in that direction, after all? Why do I have the right to look toward Turkey, but not beyond the Prut? What harm did Sadoveanu, Călinescu, Arghezi, Blaga, Stănescu do to me?” These cultural references only emphasised his pro-Romanian position in contemporary debates. Second, while attacking Lupan for his ostensible pro-Stalinism and his earlier ”ideological sins,” as well as for his ambiguous position toward the regime, Vieru used an openly oppositional language, going far beyond the prudent rhetoric of early Perestroika. He mentioned a number of “hot” issues that made his speech subversive in the eyes of the authorities. Vieru spoke about “the disastrous situation in which the speech of our children finds itself, the pollution of our folklore, the intentional and offensive neglect of our native language on national television,” but he also emphasised the ecological crisis, the consequences of the 1946–47 mass famine, as well as the “physical and spiritual inebriation of the common man.” All these topics were to be exploited by the fledgling national movement in the following years and served as mobilising slogans for the anti-regime opposition. Toward the end of his speech, Vieru launched a rhetorical tirade against his opponent, using this pretext in order to voice a number of social and political grievances:

“Do you know that, behind our literary distinctions and prizes, we are witnessing, in broad daylight, a real linguistic disaster? Do you know how distorted and ugly is today the speech of our children, youth and even older people? Do you know that the few Moldavian kindergartens in Chișinău are full to the brim and it is impossible to enrol your child there? Do you know that, out of seventeen hours of TV broadcast every day, barely two or three, and sometimes even fewer, are reserved for TV shows in our native language?!...Do you know that our villages, which preserved our national being, are being depleted of their people and their soul?”

This radical and impassioned speech was met by the audience “with applause,” marking a change of tone and atmosphere that foreshadowed the later role played by the writers in the national mobilisation against the Soviet regime. The Writers’ Conference of May 1987 represented a turning point in the radicalisation of political discourse, with Vieru and some of his nationally oriented colleagues positioning themselves at the forefront of the emerging oppositional movement.

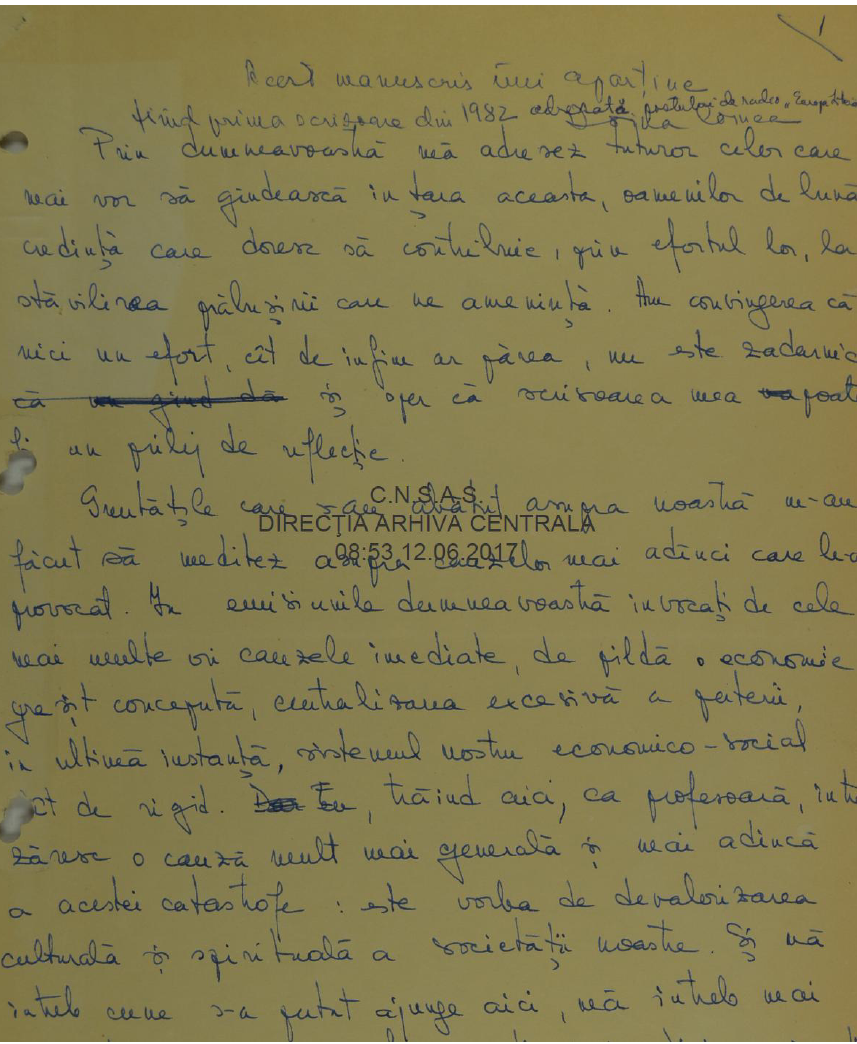

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

Cornea, Doina; Combes, Ariadna. Letter to those from home who did not give up thinking with their heads, in Romanian, 1982. Manuscript

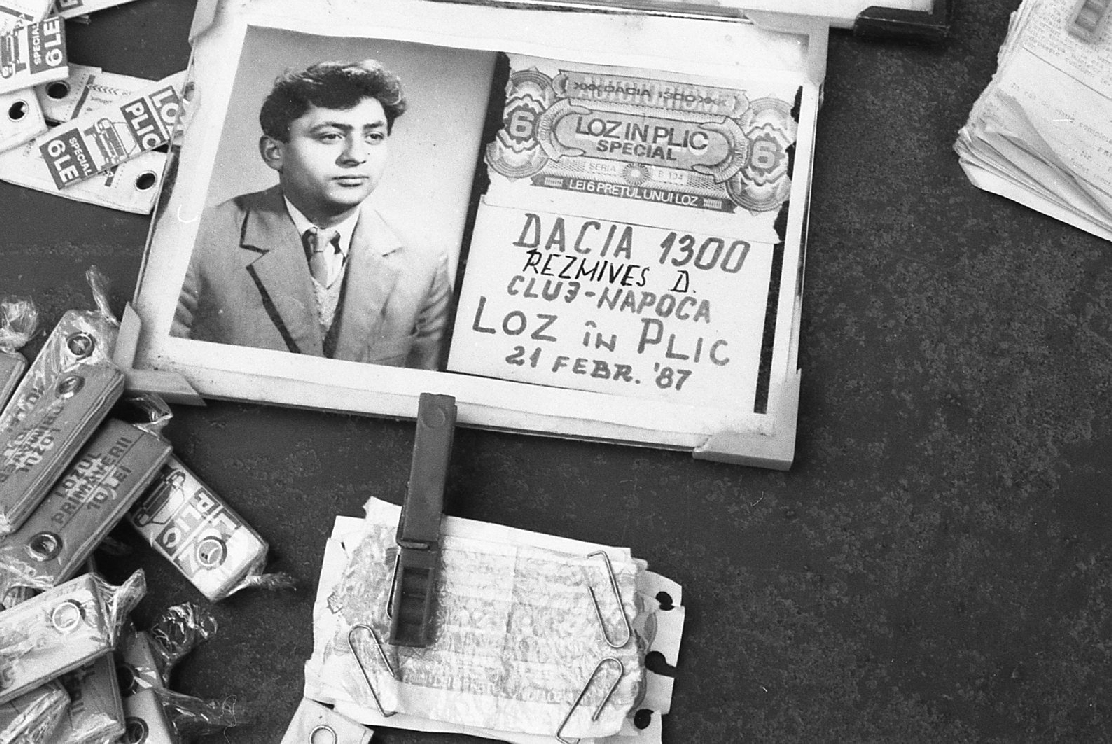

After listening in November 1987 to the news broadcast by Radio Free Europe (RFE) about the anti-communist revolt of the workers in the factories of the city of Braşov, Doina Cornea openly displayed her solidarity with the protesters. On 18 November 1987, she drafted 160 manifestos, which were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in several public spaces in Cluj (Cornea 2009, 194–195). Consequently, on 19 November 1987, she and her son were arrested by the Securitate after a detailed home search (Cornea 2006, 203). During home searches on 19 and 23 November 1987, the Securitate confiscated many documents from Cornea’s private dwelling, including all the drafts of her letters to RFE.

Among these documents, the Securitate confiscated the handwritten draft of the first letter she sent to RFE entitled: “Letter to those from home who have not given up thinking with their heads.” According to interviews granted by Doina Cornea, this letter was drafted by Cornea and her daughter Ariadna Combes in July 1982 (Cornea 2009, 169-170). The document was smuggled to the West and sent to RFE with the help of her daughter, who chose to remain in France in 1976 and visited her mother in July 1982 (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 11). In August 1982, the letter was broadcast by RFE during the radio programme “Talking with RFE listeners.” It was the first letter in a series of twenty open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE in the period from 1982 to 1989, through which she asserted herself as one of the most prominent Romanian dissidents (Cornea 2009, 195–196). The open letters sent by Doina Cornea to RFE intensified the surveillance and repressive actions of the Securitate, which had already been monitoring her closely since 1981. Due to the fact that the strict surveillance in communist Romania did not allow the development of a samizdat and tamizdat milieu, RFE played a key role in conveying the messages of Romanian dissidents to their fellow citizens (Petrescu 2013, 277).

The letter starts with a reference to radio programmes of RFE that had been previously broadcast. During these radio programmes, journalists specialising in East European issues had dealt with the crisis that affected communist Romania during 1980s and identified political and economic factors as the immediate causes. Instead of these causes, Doina Cornea emphasises in her letter causes relating to moral and cultural values. By idealising interwar Romania, she brings into discussion the destruction of the Romanian intellectual elite during the first two decades of communist rule and the decay of the educational system. In Cornea’s opinion, this “spiritual crisis” is illustrated by the everyday “compromises” and “lies” that citizens living under a communist dictatorship have to “accept and circulate” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f.1). Her argumentation in this respect is similar to that developed by Vaclav Havel’s essays and epitomised by his principle of “living in truth” (Havel 1990). Cornea argues that “the people is fed only with slogans,” which stifle all openness towards “truth, revival, and creativity” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 2–3). She criticises the conformism of Romanian intellectuals and state policies which limit theoretical education (especially the humanities) and promote technical education in order to fill the need for cadres in the rapidly growing heavy industry.

She concludes her text by asking for a reform in the educational system and encourages those working in this field at least to take advantage of the limited possibilities available to them to promote what she considers to be authentic cultural and moral values. According to Cornea, those working with students should not teach them “things in which they themselves do not believe” and they should “encourage the creativity of young people and not be afraid to say what they think” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 4–5). At the end of the letter, Doina Cornea inserted her name with the mention: “for the messengers of RFE listeners” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 5). She did not intend to reveal her real identity to the listeners of RFE, but just to prove the authenticity of the document to the editors of the radio programme. Due to a misunderstanding, her real identity was revealed during the radio show.

In November 1987, after the draft of this document was confiscated by the Securitate, the secret police used it as an argument of accusation during Cornea’s interrogation. This focused especially on the channels used by Cornea to send the letter to RFE. Although she did not mention it during the interrogation, the Securitate suspected that her daughter Ariadna Combes had helped her in this respect. For this reason, Cornea’s daughter thereafter did not receive a permit to enter the country to visit her family until the fall of the communist regime.

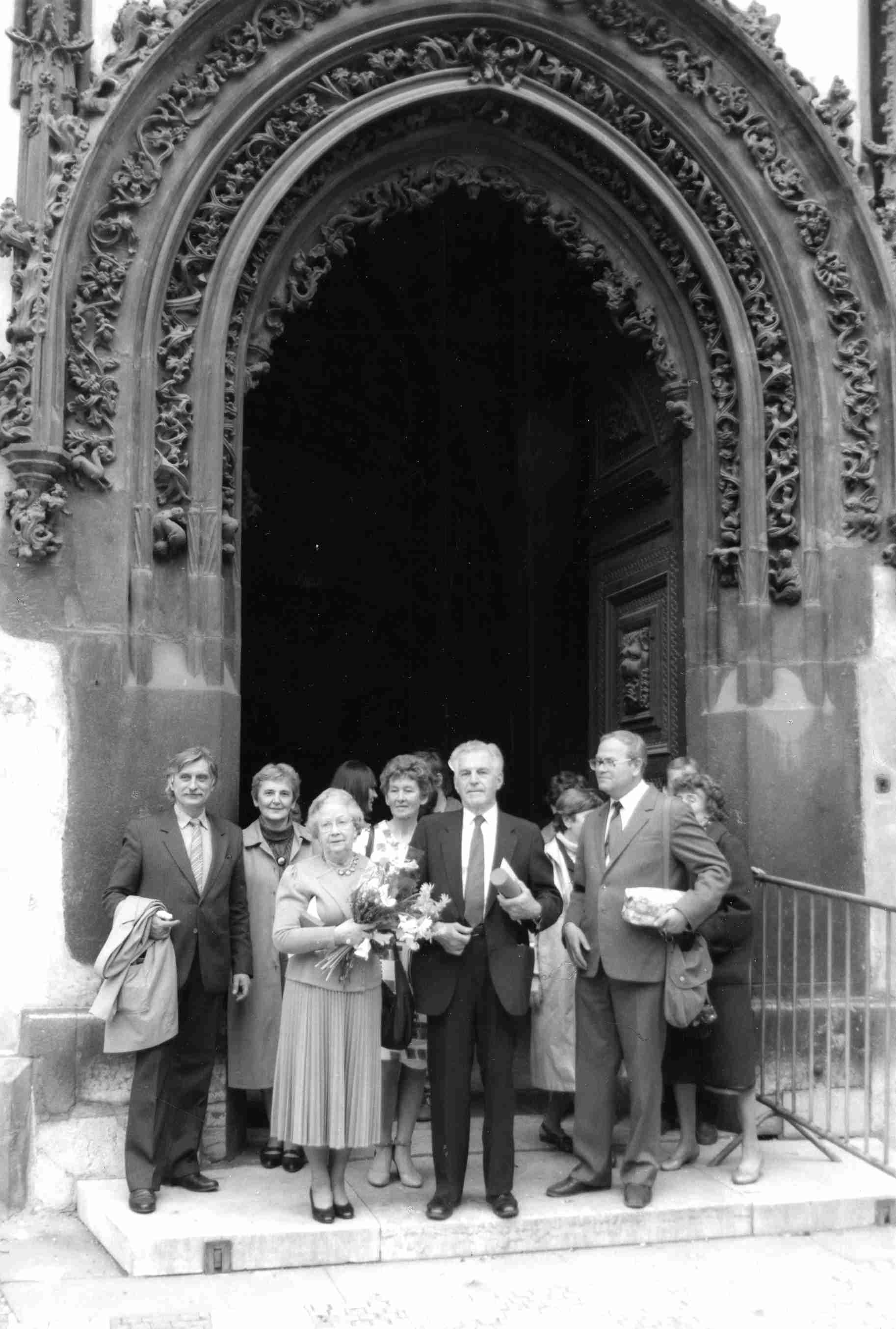

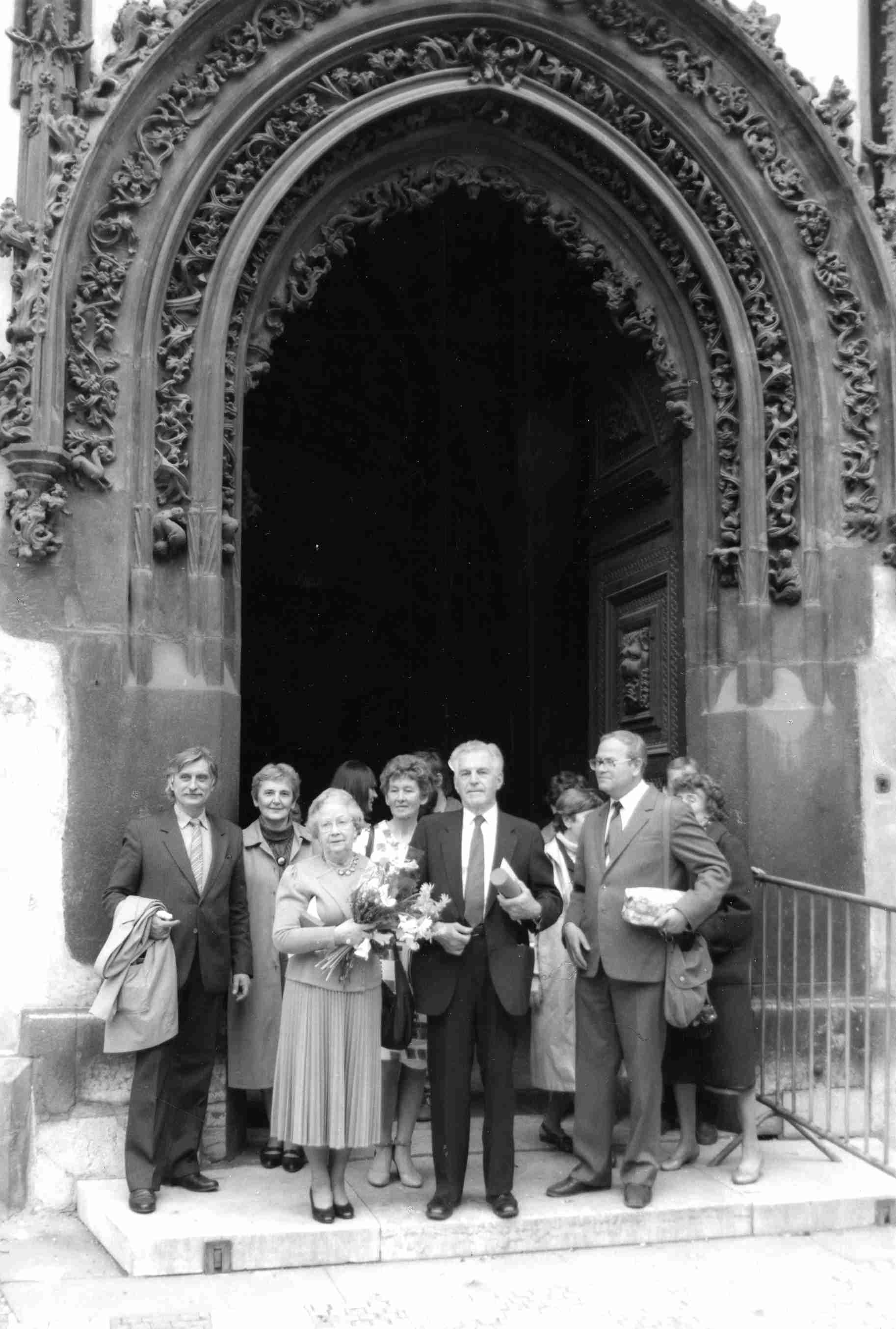

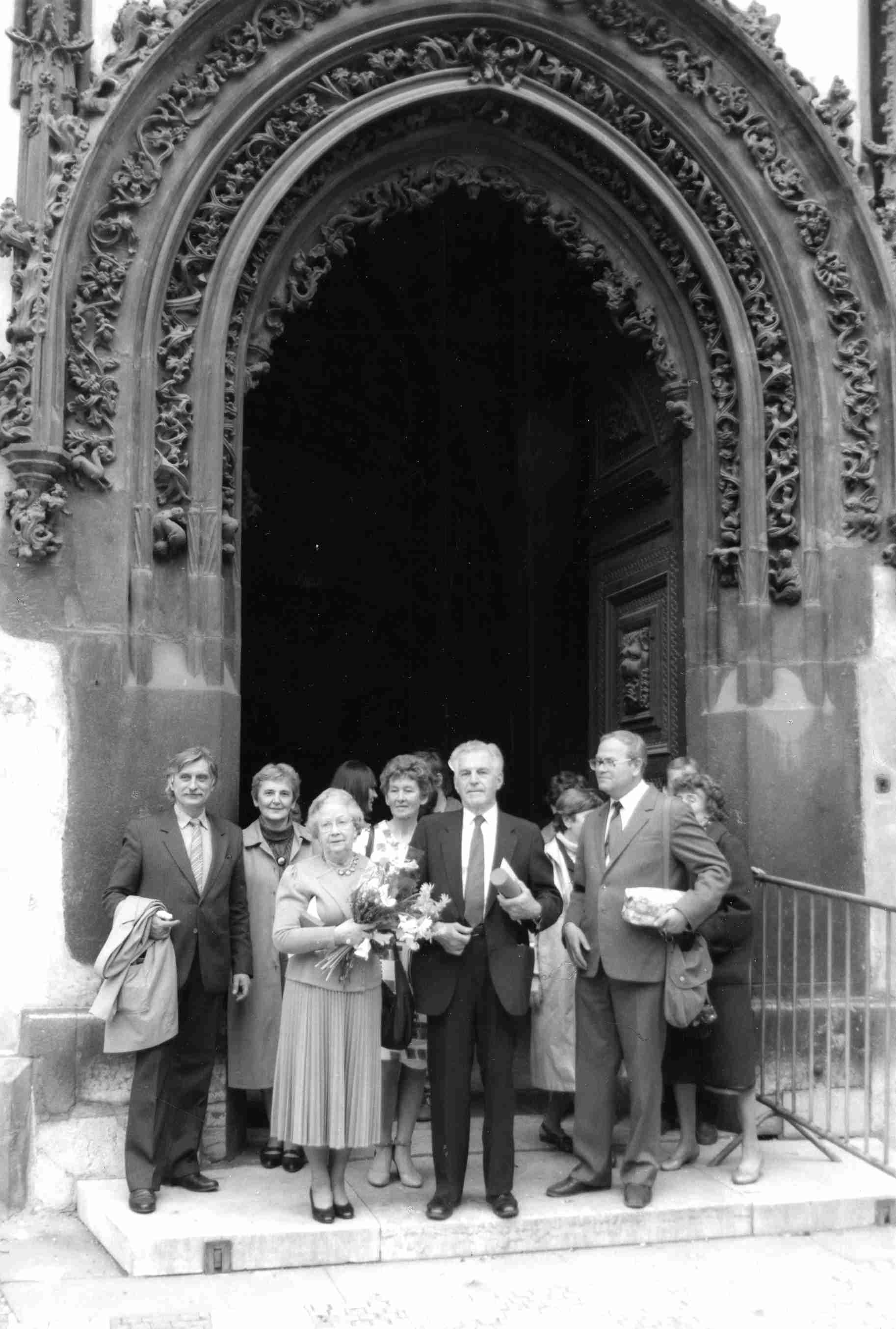

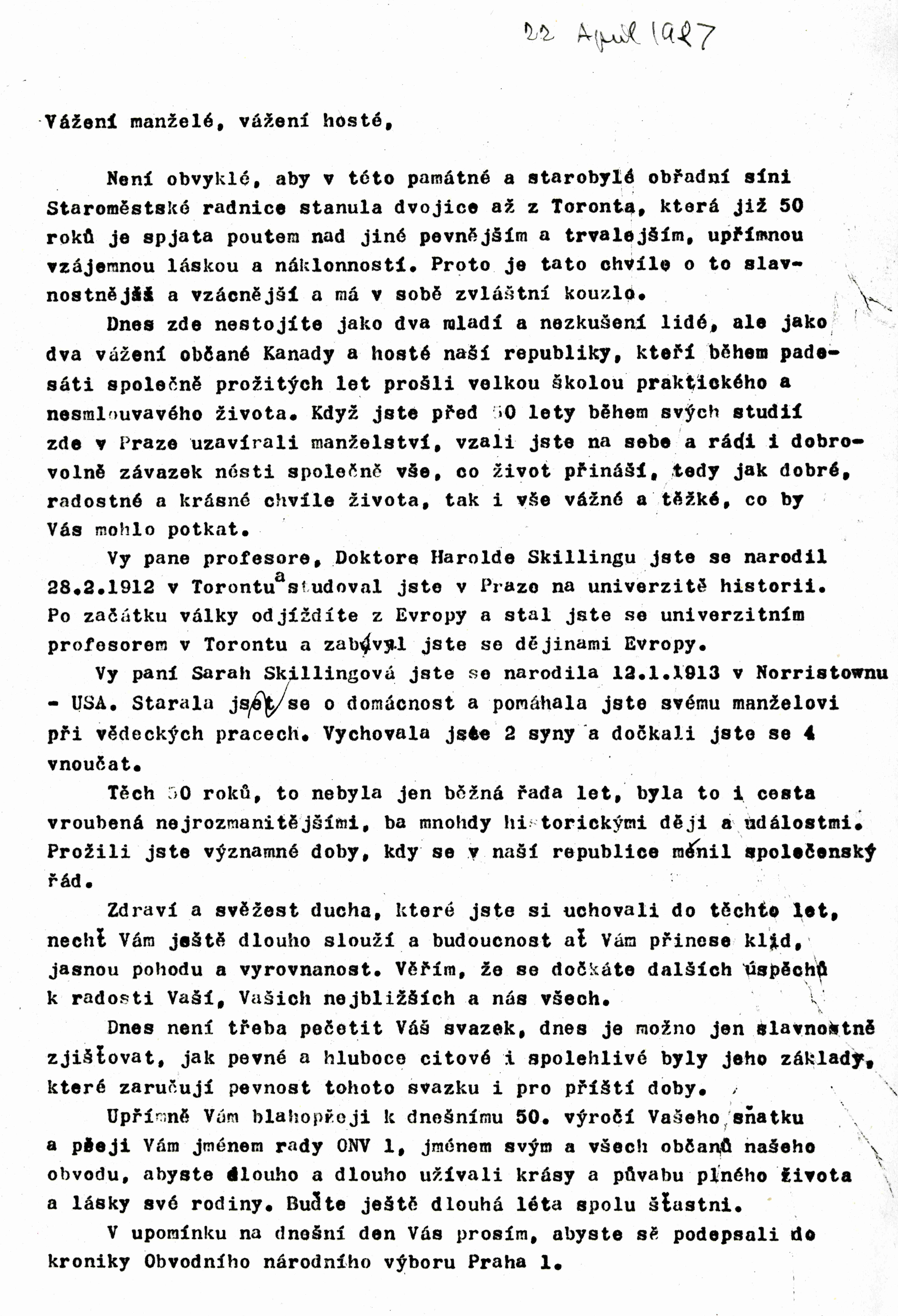

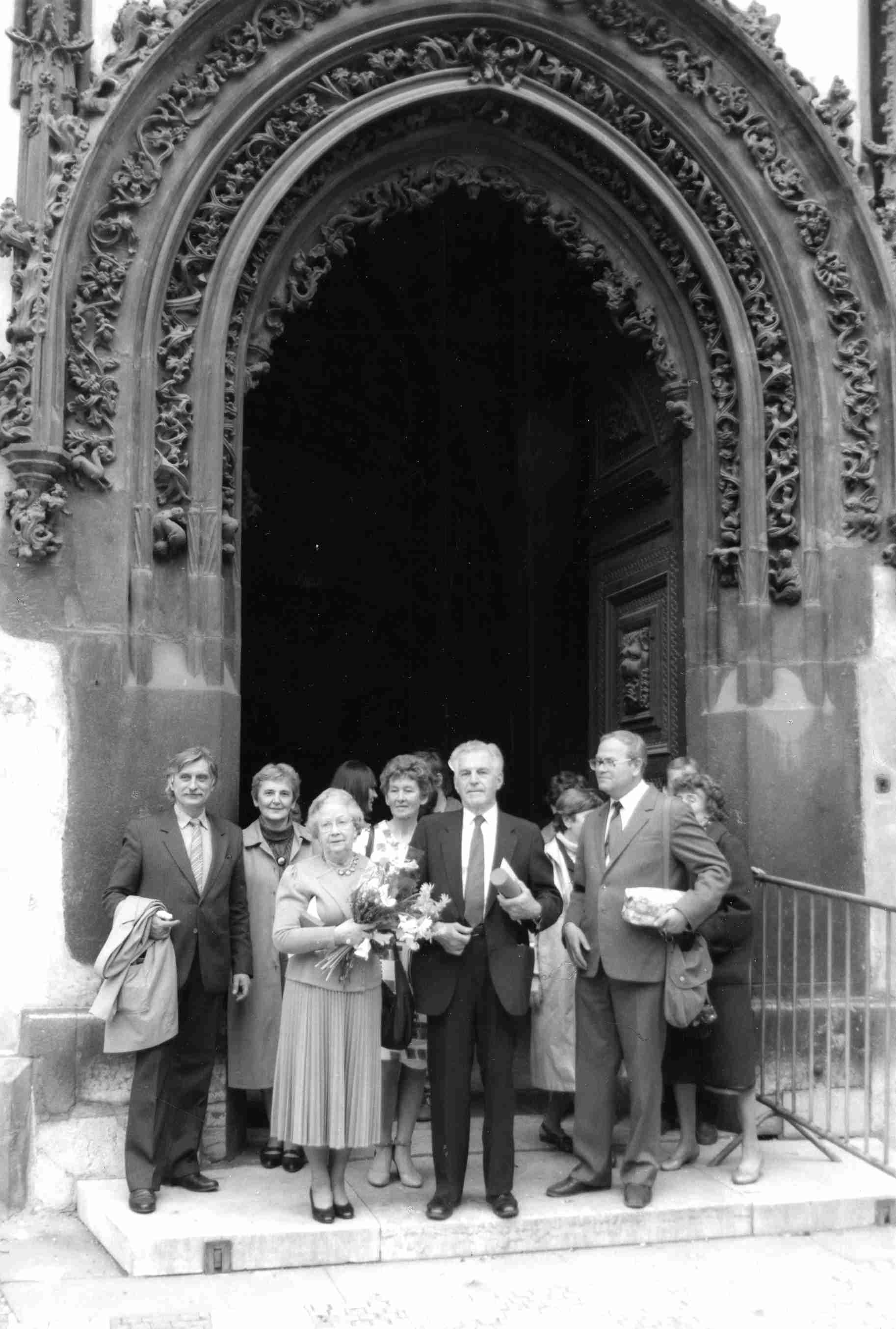

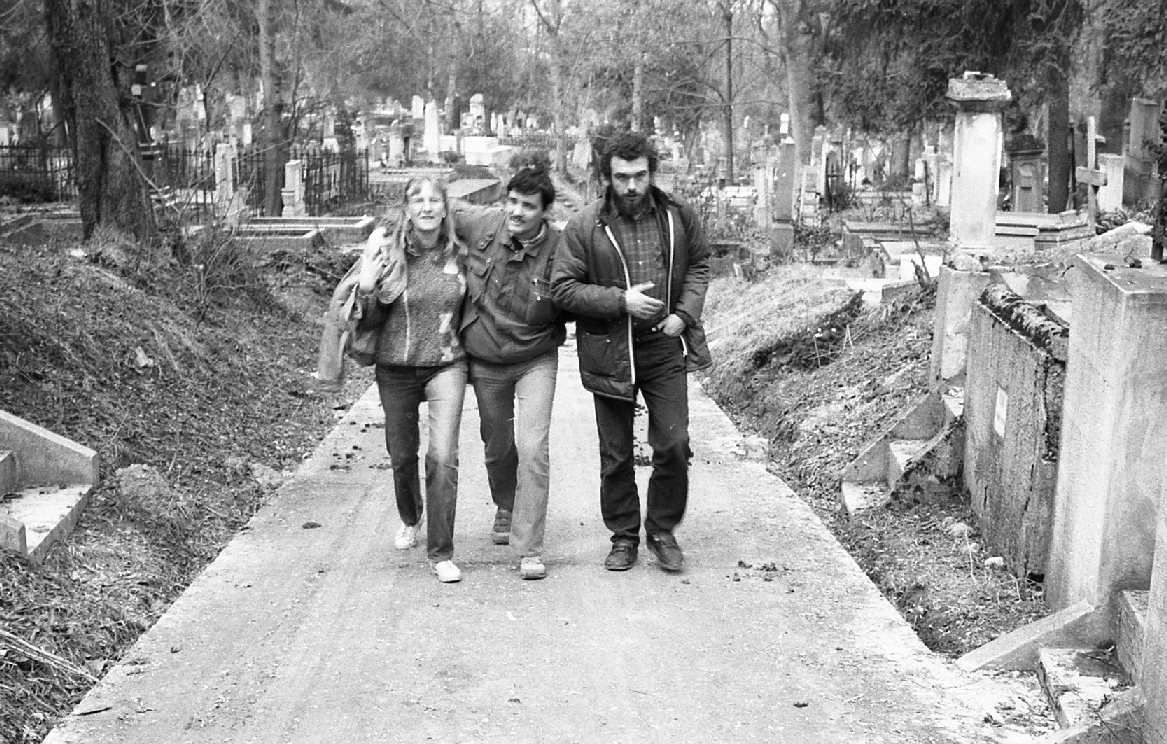

Skilling’s Golden Wedding anniversary, was at the Old Town Hall in April 1987. The journey Gordon Skilling made to Prague in April 1987, marked the celebration of Skilling's 75th birthday and the 50th anniversary of his marriage to Sally. The wedding ceremony was arranged by his dissident friends in the Old Town Hall, which was also the same ceremonial hall where they were married in 1937 (their wedding in October 1937 took place during G. Skilling’s first time in Czechoslovakia, where he studied the History of Central Europe as a student of London University). The anniversary celebration was a delicate irony in which the guests were fond of - a tribute to the "enemy of the state" because the Communists had released a number of dissidents which they had not known about. The next day in the Prague Evening, the news appeared, with a somewhat funny title, "Wedding Overseas". Jiřina Šiklová gained a great credit for this, because she paid the newspaper editors with the make-up from Tuzex at that time.

Gordon Skilling himself remembers this after years in an interview with Lidove Noviny in June 1993: "It was an interesting ceremony because perhaps all Czech dissidents - Havel, Pithart, Dienstbier and others - were present. It was strange that, in this honest ceremony, the chairman of the National Committee for Prague 1 spoke about what I did for Czech history. But he did not know that I also wrote a book about the Prague Spring, a book on Charter 77 and other things. He did not know it, and so he was very glad. Absurd situation. But the dissidents liked it. They were smiling internally. And then we had a gala dinner at the Municipal House. I like to recall the event."

The collection consists of three photographed copies of the periodical Auseklis (October-November 1987; January 1988; April 1988). It is not at present exhibited in the display of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia in its temporary location, but it will be shown in the permanent exhibition after the renovation of the museum's permanent building. The Auseklis review is a brilliant example of what the focus of public interest and discussion was in the early years of the development of the pro-independence movement.

The work of Adriena Šimotová that is in Jindřich Štreita’s collection is one of the many large-scale paper works that the artist has created since the 1970s. This is a body print imprinted in several layers of paper, highlighted with a blue pigment. Like the Polish sculptor Magdalen Abakanowicz, Simot formed her own body with touch. In many of her works she has attempted to wipe out the difference between the creator and his work. She wanted a physical gesture, such as a print of the body, the face or the limbs, to literally be incorporated into the work. Therefore, the traditional canvas was replaced with fine laminated paper or linen sheets. The paper, which symbolized vulnerable and sensitive skin, layered, crackled and jerked directly on her body or the bodies of her friends. Printed bodies and their torso became the symbol of a man wounded during the ‘normalization’ period of the 1970s and 1980s.

According to Jindřich Štreit, this work of Adriena Šimotová is the most valuable work in his collection; the estimated price is more than half a million euro.

Materials of the Original Videojournal collection constitute hundreds of hours of uncut videos that captured fragments of alternative culture, dissent movements and news reports about developments in Czechoslovakia in the late 1980s. Samizdat audiovisual magazine was founded in 1987 at the instigation of Václav Havel. The Original Videojournal aesthetic and style remotely resembled television news in state media. This established form of news allowed it to target a wide audience while at the same time criticising the restricted view of the official media.

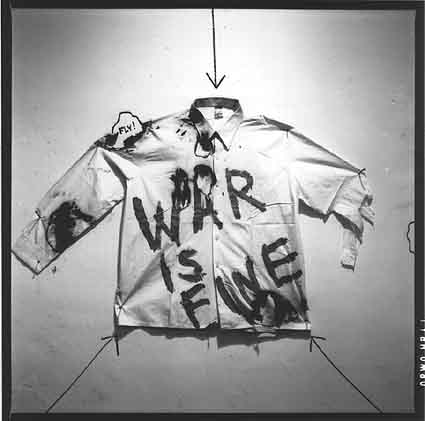

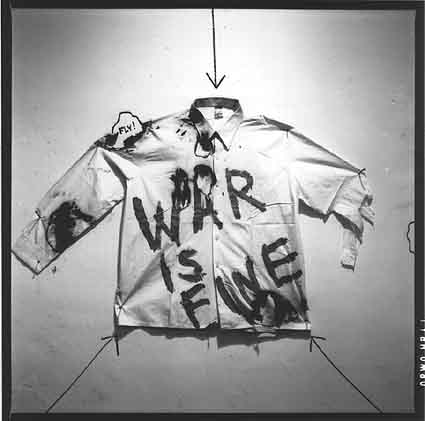

Milan Knížák is an artist associated with Fluxus and the organiser of the first Happenings in Czechoslovakia. Together with Jan Mach, Vít Mach, Sonia Švecová, Jan Trtílek, and Robert Wittmann, he founded the group Aktuální umění (Actual Art) in 1963, but the group removed the word “art” from its name in 1966 and was known as Aktual from then on. Aktual proclaimed a complete union of art and life, and it strove to awakening people’s awareness of life in art and art in life.

Liget Gallery invited Knížák to hold a solo show in 1987. The exhibition was thoroughly documented, because the gallerist knew that he would not have been able to hold a similar exhibition in Czechoslovakia. Novotny Miklós and Székelyhidi Sándor made photographs, as did Tibor Várnagy and István Halas, and György Durst made a video (the video unfortunately has been lost). Many local artists joined the action, and all participants were given a shirt for the occasion, and Knížák painted the shirts and the faces and hands of the participants.

The next day, Knížák showed his films in the Kassák Club. This was followed by a talk-show conversation between Knížák and art historian László Beke. At one point, someone ran into the room from the office with the news that Tamás Szentjóby, a well-known artist in exile, was on the phone. Knížák went to the office to take the call, and Szentjóby told him that “the greatest Czechoslovak artist has died today.” He was referring to Andy Warhol, whose death was in the news only one or two days later. Knížák had known Andy personally, so the rest of the evening became a personal commemoration.

A couple of weeks later, the gallerist brought the materials from the exhibition to Knížák in Prague, with the exception of the shirts, which Knížák had asked him not to bring. The gallerist donated the shirts to Artpool, and the documentation remained in the Liget archive.

The red star dress was originally displayed in the short movie by the architect Gábor Bachmann: Eastern European Alarm (“Kelet-európai riadó”). The movie is an abstract critique of the late Kádár regime, focusing on social and aesthetical tensions. A woman in the red star plays an important role. Her outlook and attitude serve as a counterpoint to other characters in the middle of the breakdown. Like many of Király’s works, the red star dress has also been destroyed. Still, the photograph of the dress has been archived.

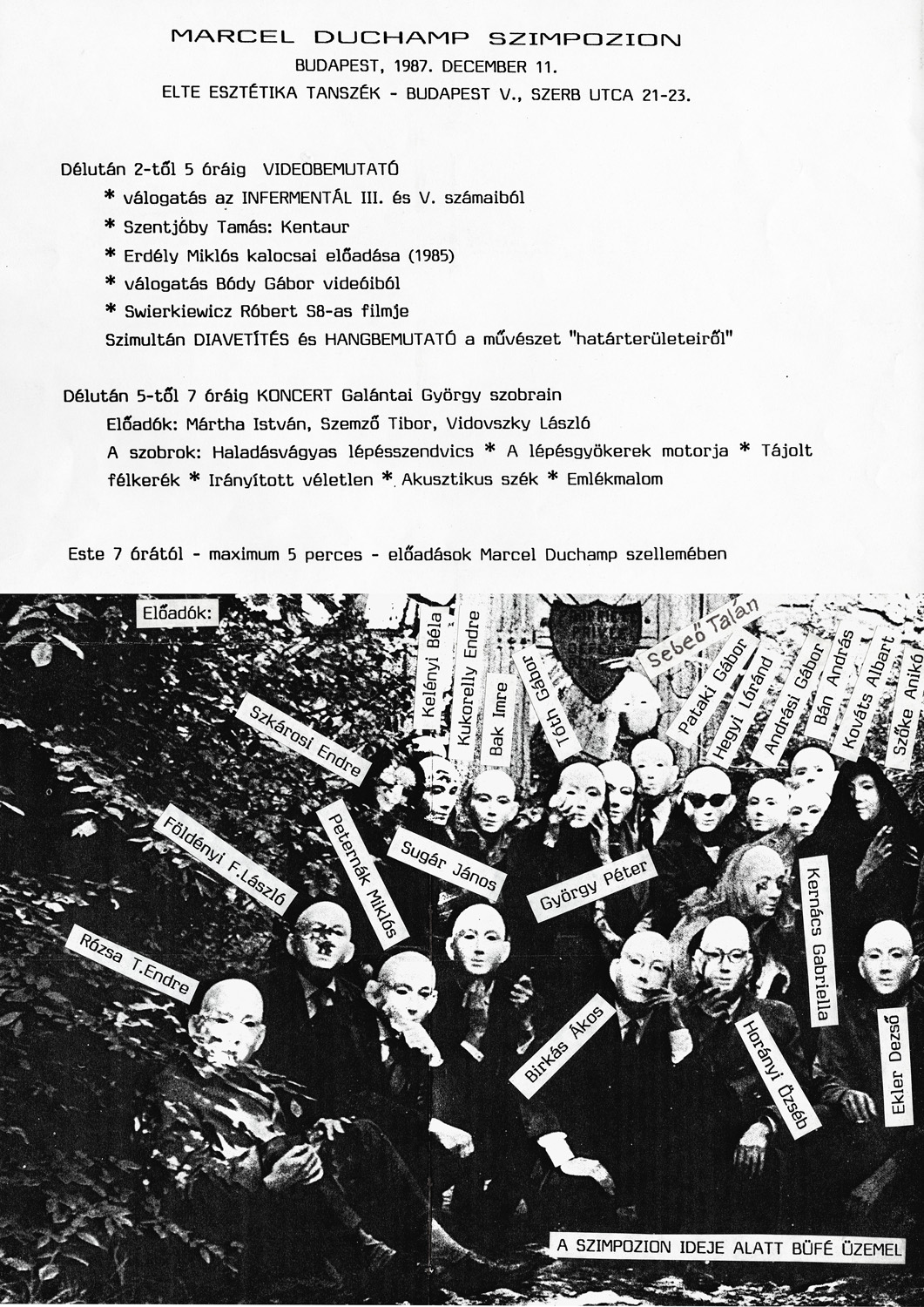

Artpool organized a symposium to commemorate the 100th birthday of Marcel Duchamp in cooperation with the Department of Aesthetics at Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest (organizers: György Galántai and Péter György). The symposium was preceded by a call for applications announced by Artpool for international artists to cooperate in the event by sending artworks, documents, projects related to the spirit of Duchamp. Among the participants, one finds artists like Vittore Baroni, Robin Crozier, Christo, Klaus Groh, Ruth Wolf Rehfeldt, etc. Artpool organized an exhibition based on the received materials entitled In the spirit of Marcel Duchamp. Concerts, sound presentations, video-screenings, slide projections and short presentations were parts of the program of the symposion. Tibor Szemző (piece for Directed Chance), András Wilhelm & Zoltán Rácz (concert on five sculptures) and István Márta (Multimedia sound improvisation on two sculptures and a video) gave concerts on György Galántai’s sound sculptures. Tamás Szentjóby’s Centaur, Miklós Erdély’s Lecture in Kalocsa and András Szirtes’ Diary were being screened. Ray Johnson’s letters, mail art and sound materials were projected from slides. The following lecturers held five minute-long talks, evoking Duchamp by measuring time with a chess clock: Gábor Andrási, Imre Bak, László Beke, Ákos Birkás, Dezső Ekler, László Földényi F., Péter György, Lóránd Hegyi, Özséb Horányi, Gabriella Kernács, Albart Kováts, Endre Kukorelly, Gábor Pataki, Miklós Peternák, Endre Rózsa T., Talán Sebeő, János Sugár, Endre Szkárosi, Annamária Szőke, Ádám Tábor, Gábor Tóth.

http://www.artpool.hu/Duchamp/MDspirit/index.htmlDifferent kinds of letters were sent to Juhan Aare. One of the most beautiful was written by artists in calligraphic writing. It shows that in some cases, letters were not just a quick response to a pressing problem, but rather works of art that were carefully composed and designed. It is a typical joint letter, signed mainly by artists from the advertising group of the Trade Administration in Tartu. The letter was signed by 34 people altogether, many of whom were related to artists. It is relatively short, like most letters in the collection, but like many of them, it also connects environmental problems with the national question. Although it is not directly mentioned in the letter, it was feared that foreign labour for the planned phosphorite mines would settle in Estonia, which would threaten the survival of the Estonian nation. In the letter, the phrase ‘Our children, grandchildren need [...] the persistence of the nation’ is used. The letter was sent to Estonian Television, but it was actually in the possession of Juhan Aare until he deposited his collection with the Estonian History Museum.

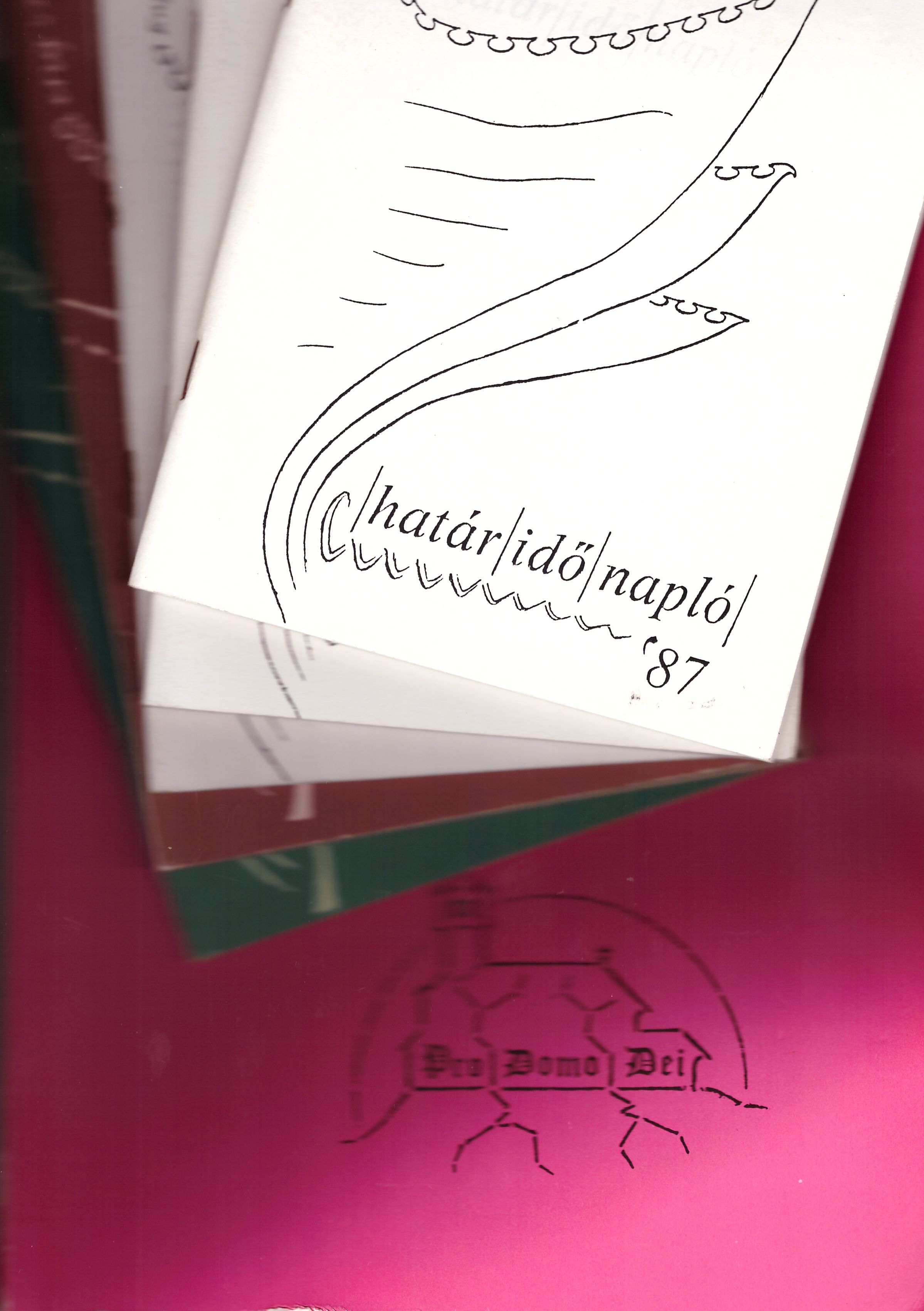

Limes was a circle of Hungarian dissident intellectuals which operated more or less actively from 1985 until the 1989 Romanian revolution. The aim of the circle was to provide a pluralist platform of cooperation for Hungarian intellectuals, which meant holding monthly/bimonthly organized meetings and publishing a journal dealing with the history and actual situation of the Hungarian minority from Romania, as well as other outstanding research work pertaining to other domains. The circle was also devoted to maintaining high standards of scientific work in Romania. As there was no chance of getting anything past the censors in Romania, the plan was to smuggle manuscripts to Hungary and to publish the journal there.

The initiator was Gusztáv Molnár, who mostly due to his job as a literary editor at the Bucharest-based Kriterion publishing house had a large personal network among Transylvanian Hungarian critical intellectuals. The core of the group was represented by the following individuals: Vilmos Ágoston, Béla Bíró, Gáspár Bíró, Ernő Fábián, Károly Vekov, Levente Salat, Csaba Lőrincz, Ferenc Visky, András Visky, Péter Visky, Levente Horváth, Sándor Balázs, Sándor Szilágyi N., and Éva Cs. Gyímesi. Through the process of editing the journal, many more intellectuals became acquainted with the activity of the Limes group.

Between September 1985 and November 1986, six meetings were held in four different localities in Romania in the homes of members of the group. The meetings encompassed a presentation (usually of a manuscript) followed by a debate, and all proceedings were recorded. The series of meetings was interrupted by a search and seizure performed by the Securitate in Molnár’s apartment in Bucharest. All documents related to Limes were taken and later studied by the authorities. By this time, the plan to make four Limes issues had already been completed, and the manuscripts for the first two issues had already been collected. The contents included transcripts of the Limes debates and studies and documents covering topics such as “national minorities,” “nationalism,” “totalitarianism,” “autonomy,” and “Transylvanianism” as a guiding ideology for the Hungarian minority in Romania. The topics also included the situation of the Csángó Catholic (Hungarian-speaking) population in Romania.

The Limes group ceased its activity after the intervention of the Romanian secret police, and in 1987, summons and warnings were issued to the members of the group. Though no more meetings were organized, after a while, Limes members resumed work on the texts. Molnár moved to Hungary in 1988, but the editorial work was continued in Romania by Éva Cs. Gyímesi Éva and Péter Cseke in Cluj. The first issues of Limes was published by Molnár in Budapest in late 1989. The content does not coincide with the initial first volume of the Limes, but the issues did contain excerpts from the debates which were held at the first two meetings.

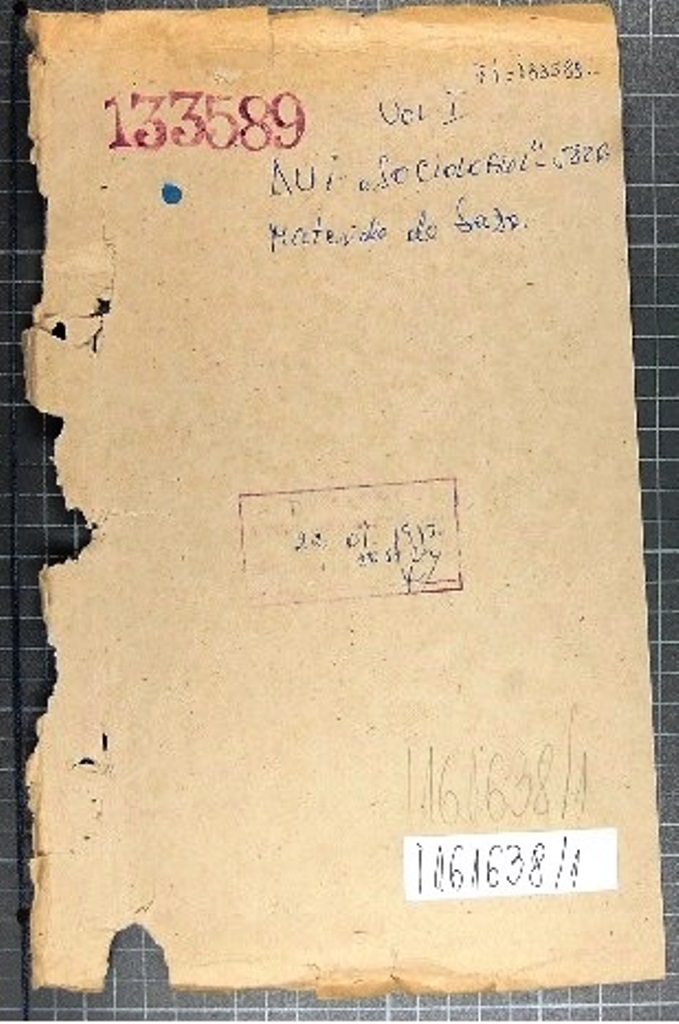

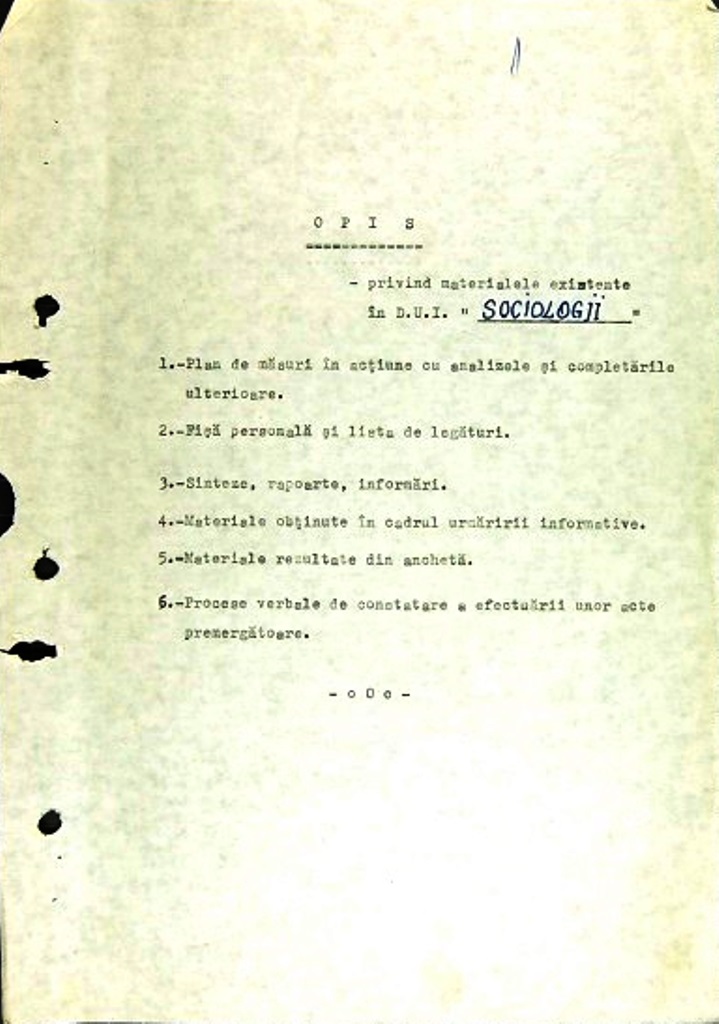

Invaluable insights into the details of the Limes story and other events in the lives of outstanding Hungarian intellectuals are provided by the Securitate files on professor of philosophy at the Babes Bolyai University Sándor Balázs (1928–), which are available for research in the Historical Collection of the Jakabffy Elemér Foundation. This is because the Limes activities in Cluj were recorded by the county agency of the Securitate as part of the information surveillance files on Sándor Balázs. His code name was “the Sociologist” (Sociologul), but the table of contents at the beginning of the dossier refers to “the Sociologists” (Sociologii), the code name used to denote the Limes group.

The dossier was opened at the beginning of 1987, and the version handed over by the CNSAS for research has three volumes which consist of some 800 folios. The files represent various types of documents: 1. strategic plans, analyses, and annexes to these plans; 2. characterizations and personal networks; 3. Syntheses, reports, and notes; 4. Information and materials obtained from surveillance; 5. Results of the monitoring activity; 6. Minutes. As noted already, the dossier contains copies of documents considered important originating from the surveillance files of other people involved in the Limes group: Éva Cs. Gyímesi (code name Elena), Péter Cseke, Gusztáv Molnár (Editorul), Lajos Kántor Lajos (Kardos), Ernő Gáll (Goga), Sándor Tóth (Toma), and Edgár Balogh (Bartha).

After sending two open letters to RFE in the period 1982–1983 and discussing with her students texts by Paul Goma and Mircea Eliade which were not officially published in Romania, Doina Cornea was put under close surveillance and threatened by the Securitate, in order to make her give up her oppositional activities. In June 1983, she lost her teaching position at the University of Cluj because she had refused to cede to these pressures. Despite these repressive measures against her, Cornea continued to send open letters of protests and to show solidarity with other dissidents in Romania (Cornea 2009, 176–177). Among these acts displaying solidarity with other oppositional activities, those supporting the 1987 workers revolt from Braşov attracted the most violent reactions on the part of the Securitate.

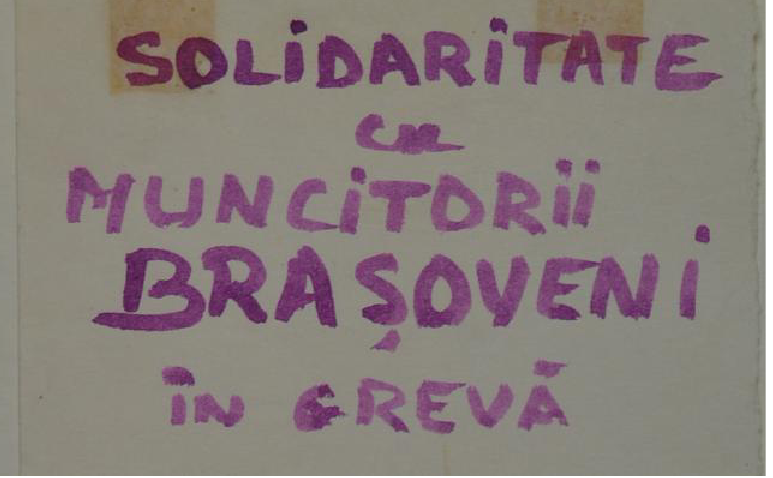

In November 1987, Cornea learned of the Braşov workers’ revolt from RFE radio programmes. Immediately afterwards she displayed a placard in front of her house in Cluj through which she expressed her solidarity with the workers. On 18 November 1987, she drafted 160 manifestos written in violet ink on sheets of paper similar to A5 format with the text: “Solidarity with the workers from Braşov” (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 109). These manifestos were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in various public spaces in Cluj, namely in the main squares and in factories (Cornea 2009, 194–195). On 19 November 1987, Cornea and her son were arrested by the Securitate and its employees conducted a detailed home search (Cornea 2006, 203). On this occasion the ink with which these documents were written and some copies of the manifestos were confiscated. The latter would be attached to the criminal file and invoked as proofs of the accusation during Doina Cornea’s interrogation by the Securitate in late November 1987 (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, f. 109).

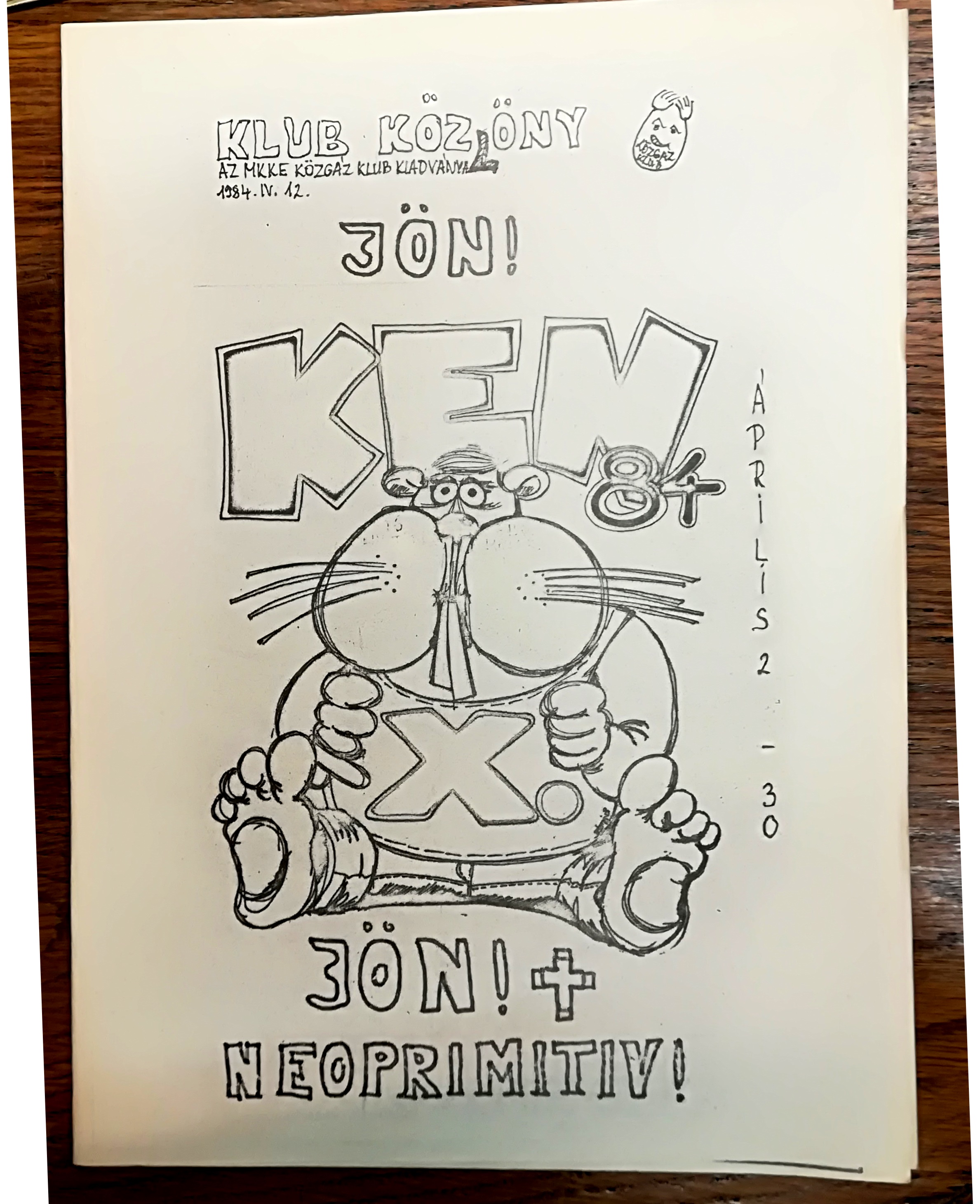

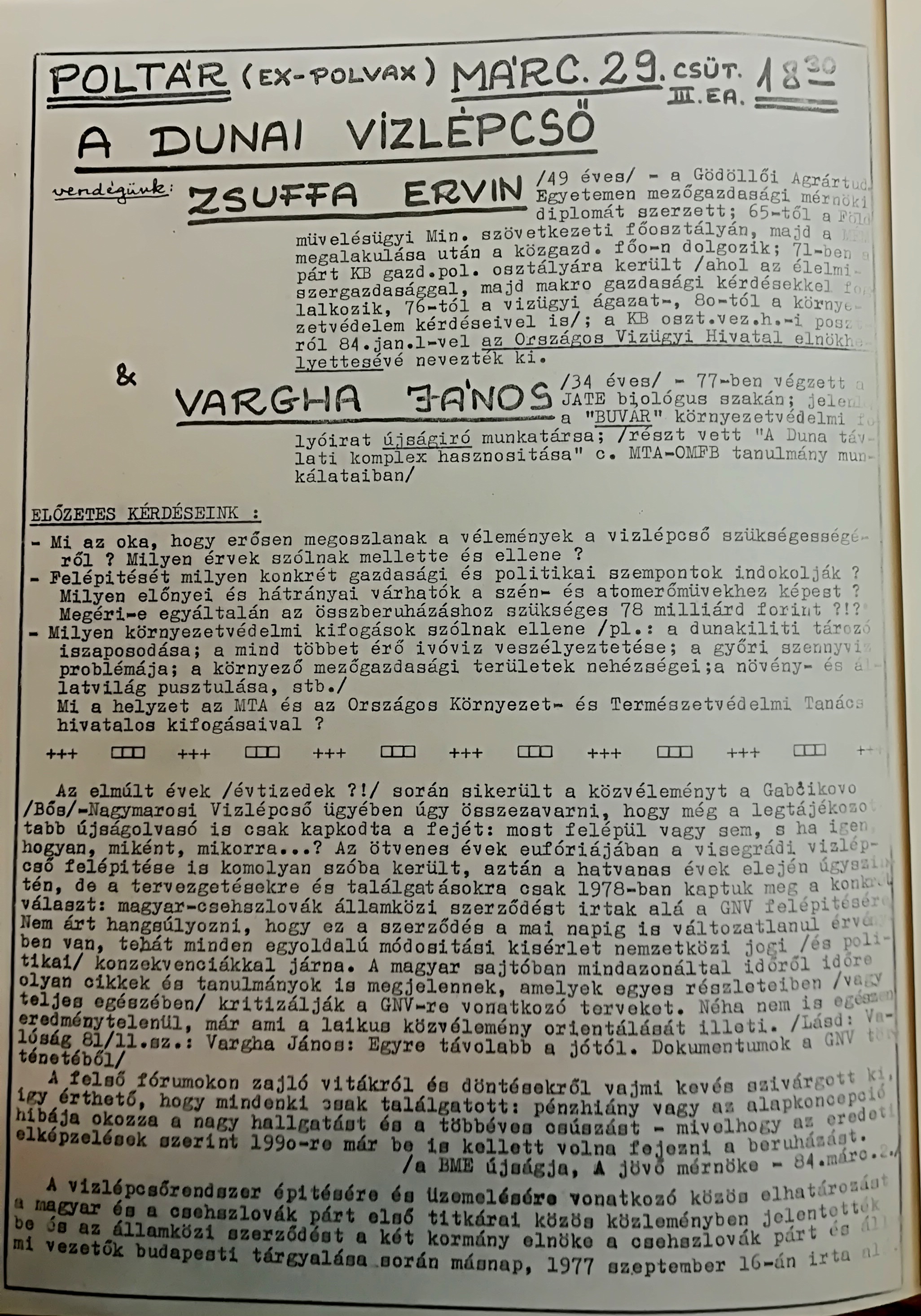

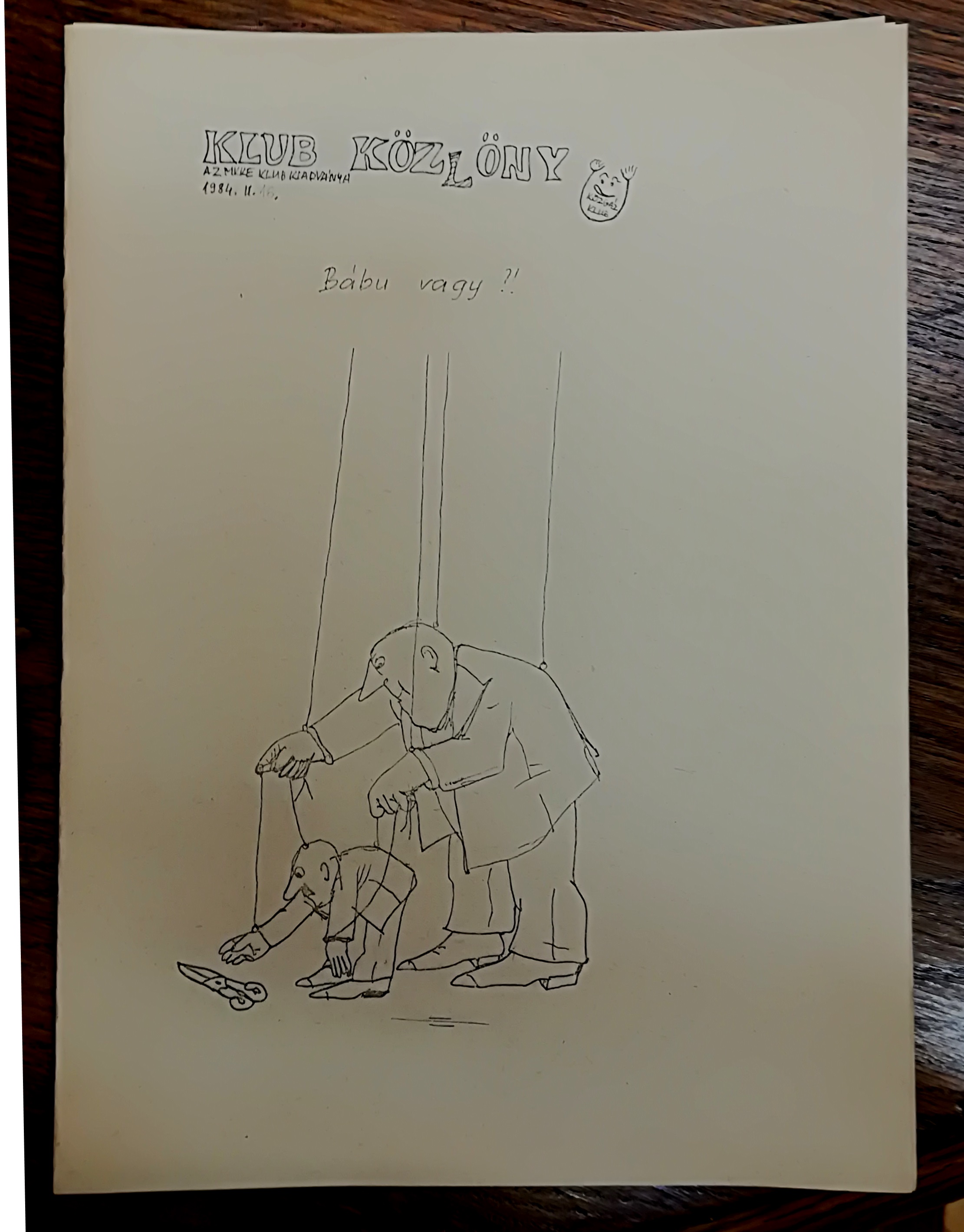

The Klub Közlöny (Club Gazette) was the self-published newspaper of the Közgáz-klub (Economics Club) at the Karl Marx University of Economic Sciences (MKKE) between 1976–1987. In the newspaper, articles were published about the club’s activities and also cultural and political topics. In contrast to the official organ of the Communist Youth League (KISZ) titled Közgazdász, there were more direct and honest writings about life at the university in the uncensored Klub Közlöny, and its tone was many times more critical of the party leadership of the university. The aim of its creators was to galvanize the students and to develop the culture of debate. The issues are preserved in the archive of the Corvinus University and in the National Széchényi Library.

![Halottaink [Our Dead], 1987. Book](/courage/file/n74231/halottaink-12144397-eredeti.jpg)