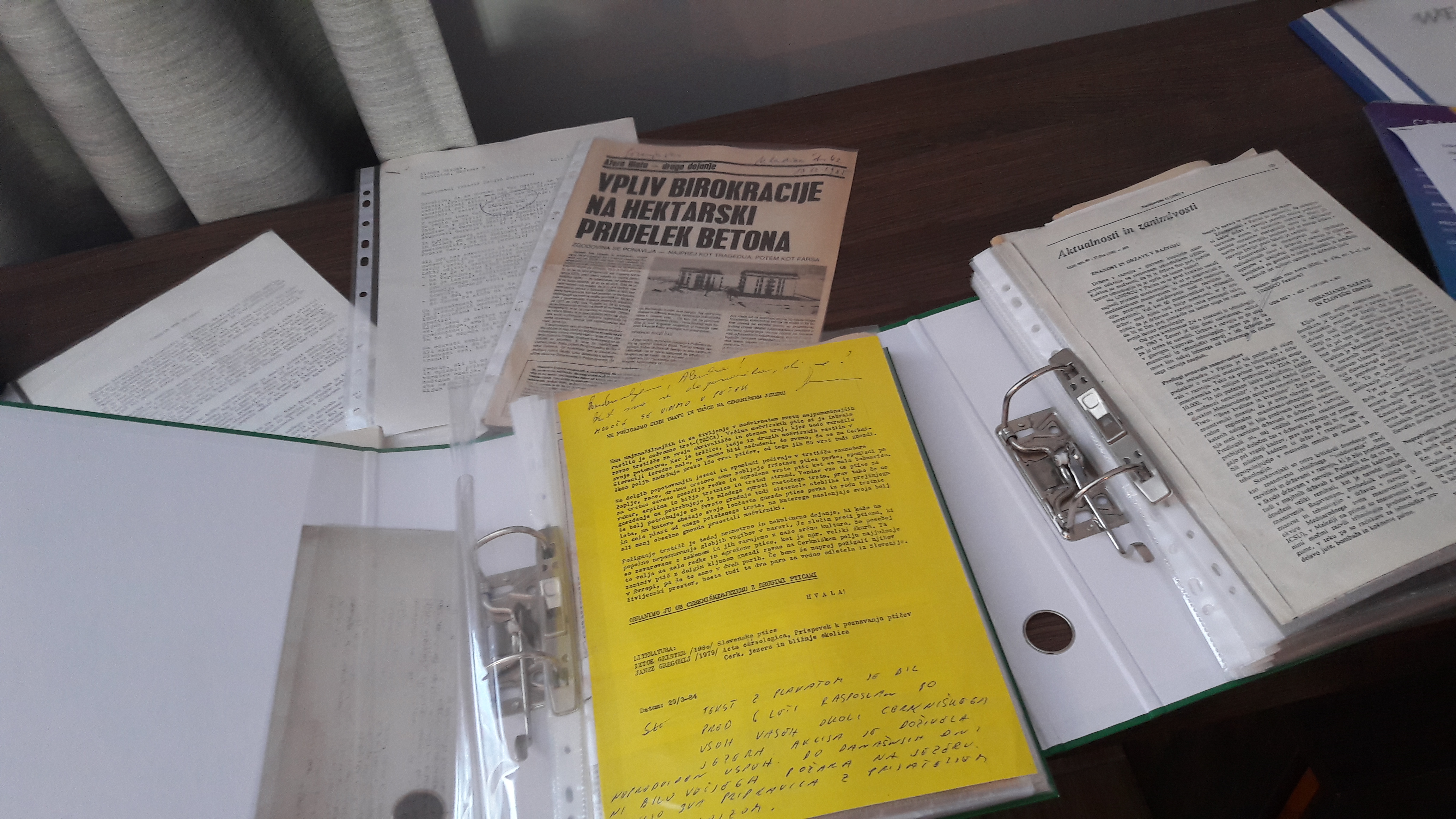

Scrisoarea oficială a Secretarului Comitetului Orășenesc de Partid Odesa către Secția Cultură a CC al PCM (în limba rusă), 29 iulie 1970

Scrisoarea oficială a Secretarului Comitetului Orășenesc de Partid Odesa către Secția Cultură a CC al PCM (în limba rusă), 29 iulie 1970

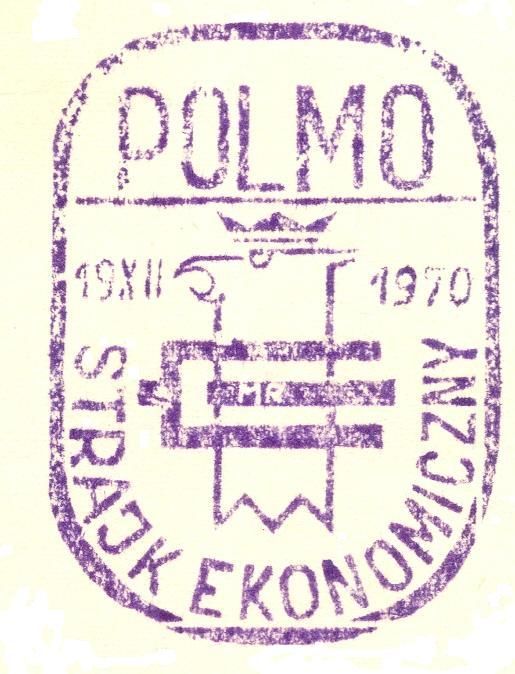

By the second half of 1970, Noroc had reached a wide and growing popularity. Its frequent tours throughout the entire Soviet Union were tolerated and encouraged by the local Moldavian leadership, including for financial reasons. However, the strategy of dissimulation applied by its members, which presupposed the existence of two parallel programmes and repertoires, led to dire consequences. Between 15 and 18 July 1970, Noroc gave a series of concerts in Odessa, a city where it had performed before and where it had received a particularly warm reception. The concerts took place in the city’s central park, at the Summer Theatre. Inspired by its recent success at the Slovak music festival Bratislavska Lira, the band unleashed a frenzied and violent reaction on the part of the Odessa audience, which included a number of “Soviet-style hippies” and other “marginal” elements representative for underground youth subculture. In its enthusiasm, the mob yelled, smashed seats and ultimately set the Summer Theatre on fire. These events, which were reminiscent of a Western rock festival, placed the party authorities on high alert. The Odessa party secretary, Ovcharenko, remarked that Noroc had “provoked the discontent of socially active citizens and of the vast majority of the audience” even during its previous performances. This time, however, things had apparently got much worse: “Its recent performances provoked a particularly unhealthy agitation among a certain part of our youth, mostly among fans of ultra-fashionable foreign jazz music.” Ovcharenko then harshly condemned “the ideological and artistic quality” of Noroc’s performance, which he found “vulgar and low-brow” [nizkoprobnaia]. He also questioned the group’s professionalism, since, in his view, the band displayed a “lack of any elementary musical culture.” Ovcharenko’s decision was rather harsh, demonstrating the genuine alarm of the Soviet authorities: “it is henceforth prohibited for the Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra to plan” Noroc’s concerts in Odessa. The band was thus effectively banned from the city. In conclusion, Ovcharenko expressed his wish to see another kind of Moldavian music, one that would exhibit “a vivid, professional form and a higher ideological and artistic level.” This attack by the Odessa party officials was coupled with a press campaign in the local newspapers in Odessa and Vinnitsa (another Ukrainian city where Noroc had performed that summer). Several letters from angry members of the audience blasted the band for its Western style and “un-Soviet” behaviour on stage. The letter from Odessa seems to have been the main argument behind the official decision to dissolve the band in September 1970. The members of Noroc were informed about their fate by the director of the Moldavian Philharmonic Orchestra, Alexandru Fedco, on 10 September 1970. However, the official decision was only issued on 16 September. The order of the minister of culture of the Moldavian SSR, Leonid Culiuc, approved by the head of the Cultural Section of the Central Committee of the CPM, Pleshko, mentioned the “frequent complaints of the public” as the ostensible reason for Noroc’s suppression. The band was purportedly dissolved for “gross violations of repertoire policy” and for transgressions of “the norms of artists’ behaviour on stage, which are in contradiction with the tasks of our youth’s communist education.” The authorities thus recognised the subversive character of Noroc’s music and, by implication, of the lifestyle it represented. Even despite the intentions of the musicians, the regime construed any deviation from the accepted cultural and social norms as a threat to be addressed and removed as soon as possible. There are obvious parallels between the musical field and similar tendencies in Moldavian literature and film, where any intimations of “Western” influence became a target for official crackdown in the early 1970s. Noroc’s emblematic musical hits were effectively banned until the Perestroika period, while its members had to find new formats for their careers. The phenomenon of “Moldavian rock” epitomised by these musicians remained, however, significant as an anticipation of things to come.

This letter was the second letter by the Czechoslovak historian and dissident Milan Hübl addressed to Gustav Husák, the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia; the first letter from February 1970 remained unanswered by Husák. Hübl could not comprehend how Husák, who had been a political prisoner in the 1950s and lived through the suffering of a communist prison himself, could restore the authoritarian regime after the repression of the Prague Spring in 1968 and persecute his opponents. In his letter, Hübl defends the former representatives of the reform movement who were stripped of their jobs for political reasons, and denounces the violation of human and civil rights in the country. “Where are the people,” he writes at the end of the letter, “who falsely charged you, interrogated you, judged you, imprisoned you and later tried to prevent your rehabilitation? You know better than anybody else which functions they hold now when you have to meet them, or the functions which you have to appoint them. You are in the snake-like grip of your former jailers.” This letter was one of the factors that resulted in Hübl’s imprisonment in 1972. Gustav Husák’s reply from 25 October 1970 is also part of the Milan Hübl collection in the National Archive.

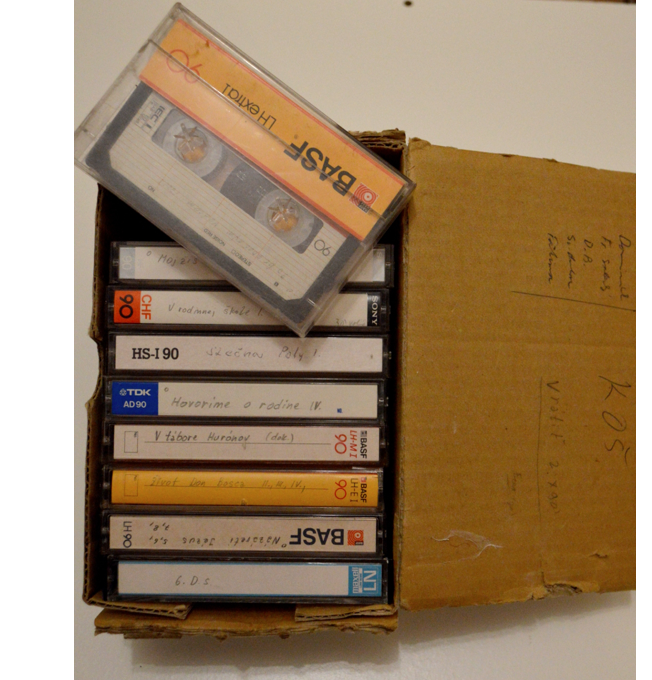

The István Darkó Legacy – Péter Egyed Private Collection, beside the documentary material of unconventional childhood activity and the sole appreciable Transylvanian Hungarian radio play of the Romanian communist regime, contains writings that – in form of fantastic stories, evading the censorship of the time – made possible the representation of an “Other“ world completely different from the Party ideology.

Group and community photographs feature heavily amongst the corpus of confiscated images in the secret police archives. Such images were often taken at pilgrimages, religious festivals and special gatherings and were a means for the community to materialise communal memory and present their values and beliefs in distinctive visual form. For the secret police they were an invaluable source of information and a convenient means of tracing networks and personal relationships in the religious underground. The photographs in the archives, therefore, represent an important resource for understanding how religious groups chose to represent themselves and how the totalitarian system used images of religious groups in order to identify, trace and incriminate their members. Photographs such as ones confiscated from pastor József Németh in 1972 form an important part of the Hidden Galleries Digital Archive, not only because of what this rich corpus of images can tell us about religious practices and spaces in the underground during communism but also because in many cases these photographs remain hidden from the communities that produced them. One of the principal aims of the Hidden Galleries Archive is to re-connect communities with lost aspects of their cultural and sacred patrimony. The photographs featured in this entry were later shown to the community from whom we came to know that the hidden house church was no longer used following the house raid in 1972 and due to ongoing surveillance the community was forced to dissolve. József Németh only succeeded in planting a new community ten years later in 1982. The new community began to gather again in the same house church. We also learned that the young girl featured in the picture of a baptism is the daughter of the pastor, who was 12 years old at that time, and that the baptism took place in the garden of the hidden church in a specially constructed font.

http://hiddengalleries.eu/digitalarchive/s/en/item/15

The magazine of the Czechoslovak Socialist Opposition, intended mainly for readers in Czechoslovakia, was published once every two months since 1971. This journal of political figures and publicists connected with the Prague Spring was created in 1970 in Roman exile thanks to the work of Jiří Pelikán, when two zero numbers with a head Forbidden Prague Literary Sheets was published. One year later, it began to come out periodically. Jiří Pelikán was originally the publisher of the magazine.

“Listy” was a left-wing opposition magazine, both domestic and exile, but they tried to remain open for authors of other political orientations. In particular, they included political studies, commentaries and analyses. Other inaccessible information from behind the scenes of communist politics, as well as small columns about the activities of communist parties in Eastern Europe (in the section “What Red Law Does Not Write”) were also published. From the beginning of its existence, “Listy” focused on political processes with opponents of the regime, and after 1977 they regularly reported on Charter 77, published committee documents to defend those unfairly prosecuted, and also regularly reprinted articles from domestic samizdat. The magazine had many authors who contributed to its publishing. Many articles were signed with ciphers or pseudonyms, and cannot be identified even today.

Scriptum.cz acquired this unique collection directly from the hands of Dušan Havlíček, who was one of the authors of the “Listy” magazine and together with his wife for many years compiled a set of registers for this important title. Dušan Havlíček only provided his collection to scriptum.cz and it cannot be found anywhere else, either digitally or in print.

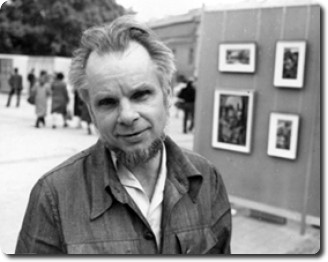

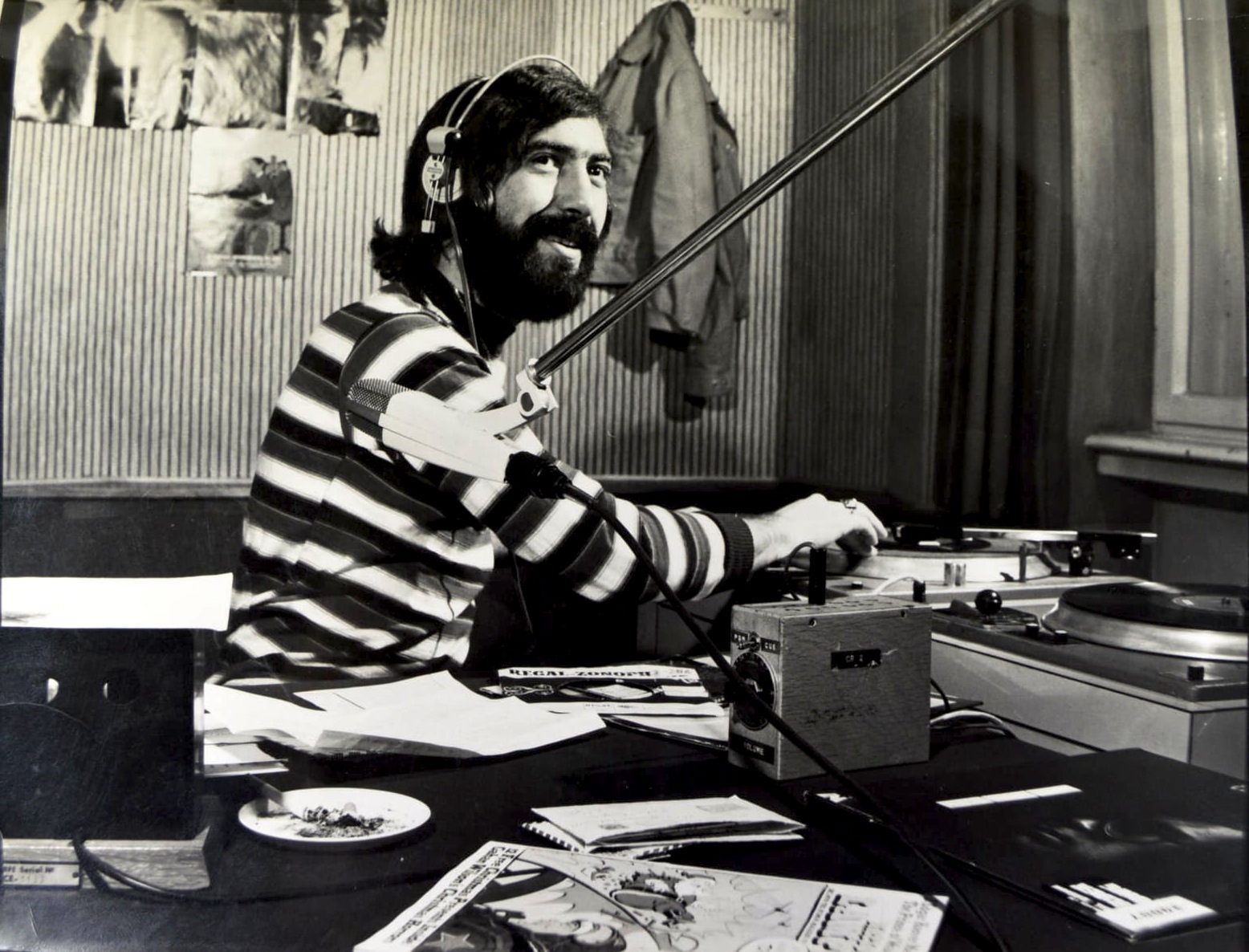

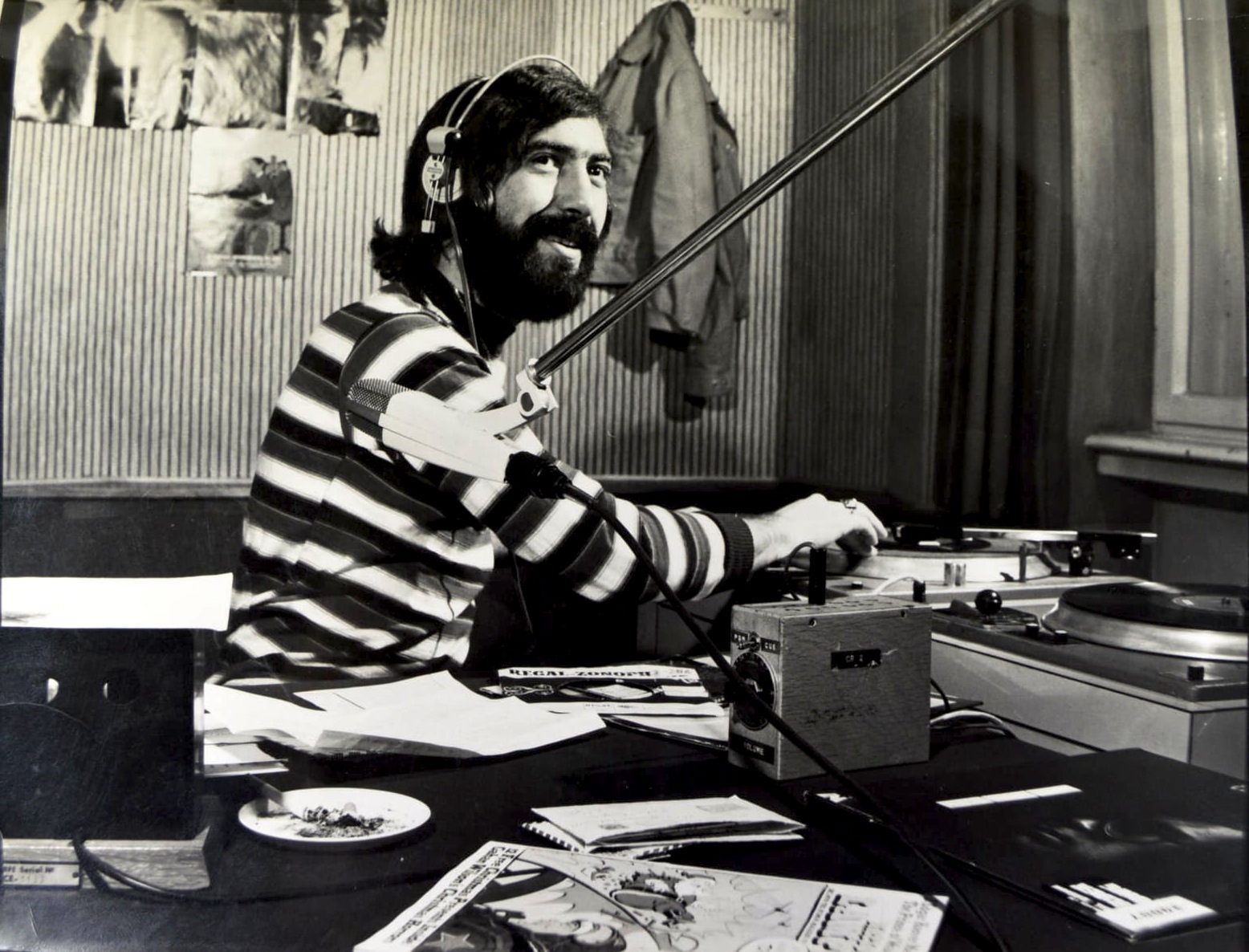

The photograph represents Cornel Chiriac during one of his broadcasts at the Romanian desk of Radio Free Europe (RFE). Taken in 1970, it was sent together with a letter to his mother in Pitești. Unfortunately, the Securitate confiscated the letter and the photograph and thus they never reached their destination. The picture is very telling for Cornel Chiriac’s passion for music and his rebellious nature. He is smiling to the camera as he is about to play one of the many vinyl records on his desk. His broadcasts at RFE enjoyed huge popularity among Romanian young people. This popularity was partly due to his passion for music, his vast knowledge about it, and the dedication with which he performed his job as radio producer at RFE. The photograph also showed the same rebellious Cornel Chiriac with long hair and beard, and a lit cigarette placed on an ashtray. The outfit, a long-sleeved striped shirt and a jacket on a hook on the wall, complete his rebellious outlook specific to the period. It is interesting to note that, although Cornel Chiriac was the idol of an entire generation, many people were not at all familiar with his face. It is from this photograph in the Securitate files that many discovered the image of their hero after 1989: “The great majority of us did not even know what our hero looked like, but he had become a lively presence, our close-faraway comrade, the protector of our sounding utopia. In a Romania, which was more and more isolated in its unhappiness, the music that Cornel Chiriac offered us represented one of the few open horizons, one of the few breaths of hope” (Jurnalul 2008). Today, the photograph confiscated by the secret police is his most widely circulated image, and it was selected by his fans to illustrate the Facebook page which keeps alive his memory (https://www.facebook.com/Metronom-In-amintirea-lui-Cornel-Chiriac).

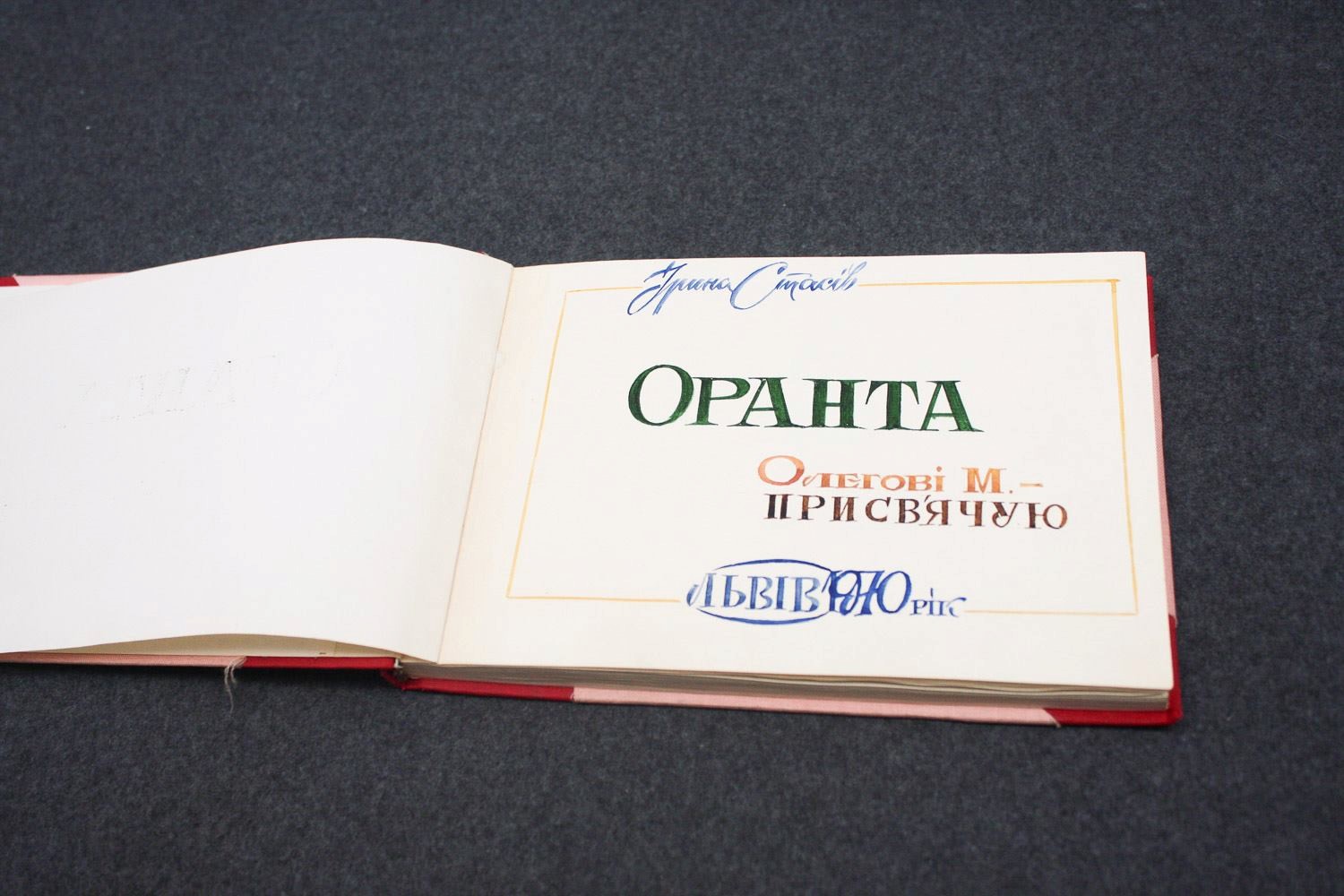

Iryna Kalynets’ volume Oranta is another featured item of the Prison on Lonskogo St. It was published in Lviv in 1970 and dedicated to her friend Oleg Mink, an artist from Makeevka, in the Donetsk region. Clearly made by hand, the illustrations were done by the artist Roman Petruk, who used watercolour, gouache and other techniques.

This book was confiscated in a search of Kalynets’ apartment following her arrest in 1972. The KGB file on her case indicates that two publishers refused to print this collected volume of poetry, partly due to the “questionable behaviour” of the author and partly because of the fact that Stasiv-Kalynets “did not once mention successes of socialism, the values of collectivism, or praise the wisdom of the Soviet leadership.” The volume along with several others penned by Stasiv-Kalynets underwent linguistic and stylistic analyses by Soviet forensic experts working for the courts, who concluded her body of work “painted socialist realities as undesirable, while also guiding the reader instead toward mysticism.” Quite a few poems were designated as clearly nationalistic, expressing disdain for Soviet rule, “profaning ‘foreigners,’ while also awaiting the moment when they would be struck by 'thunderous revenge.’” As Iryna Yezerska notes in her piece about the book Oranta, it drew on biblical themes of suffering and resurrection, calling for a beleaguered Ukraine to rise from slumber. The KGB concluded, these messages “were particularly toxic for young people, whose worldview had not sufficiently matured.”

The courts handed down a severe sentence of 6 years hard labour and another three in exile, despite the many letters written by family and friends on her behalf, who questioned the wisdom of meting out such punishment for poetry. Her husband Ihor was arrested several months later. The courts found particularly problematic the publication of a volume of his poetry abroad, which he had dedicated to Valentyn Moroz, a historian who had been arrested in 1970, as well as his contacts with ““unreasonable” people and foreigners.” He received the same sentence as his wife Iryna, which left their daughter Dzvinka without her parents for 9 years.

![RA (Rahvusarhiiv [National Archives of Estonia]), EAA.5304.1.3, p. 18-20.http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:18http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:19http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:20](/courage/file/n11161/eaa5304_001_0000003_00019_t.jpg)

![RA (Rahvusarhiiv [National Archives of Estonia]), EAA.5304.1.3, p. 18-20.http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:18http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:19http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:20](/courage/file/n4553/eaa5304_001_0000003_00020_t.jpg)

![RA (Rahvusarhiiv [National Archives of Estonia]), EAA.5304.1.3, p. 18-20.http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:18http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:19http://www.ra.ee/dgs/_purl.php?shc=EAA.5304.1.3:20](/courage/file/n29128/eaa5304_001_0000003_00018_t.jpg)

On 16 October 1970, a history student Mati Mandel gave a presentation about the beginning of the Estonian student movement in the 19th century. His presentation focused on the Estonian Students' Society, the first Estonian student organisation, which was prohibited after the Soviet annexation of Estonia. The subject was definitely not approved of by the authorities, but these subjects could be dealt with at Circle of History Students events. Also, it was not the only time that student life before the annexation was discussed. One comment from the audience is notable. It was said that the anniversary of the Estonian Students' Society was marked by émigré Estonians, which was an allusion to the fact that in Soviet Estonia it would not have been possible. This presentation draft shows notes that were probably written by someone in the audience, not by Mati Mandel himself, since it belongs to the minutes of a regular meeting. Today, it is possible that students who use the archive also read these meeting minutes.

Following the official decision to disband Noroc in September 1970, the members of this group found a temporary job at the Tambov Philharmonic Orchestra in Central Russia. This provoked a swift reaction on the part of the Moldavian Party establishment. Three months later, in December 1970, the leader of the Moldavian Komsomol (and future high Party dignitary and later president of the Republic of Moldova in 1997–2001), Petru Lucinschi, sent an official letter to his superiors in the Central Committee complaining about Noroc’s continued existence and frequent tours organised in various Soviet cities, despite its harmful ideological impact on “Soviet youth.” It is rather doubtful that this initiative came from Lucinschi himself. It was probably a move orchestrated by the Party leadership in order to legitimise its further actions and claim that it had support from below, i.e., from the representatives of the republic’s youth. In his letter, Lucinschi uses the customary Soviet jargon, claiming that Noroc “deviated more and more from the generally accepted norms of behaviour” expected from a Soviet musical group. The band is directly accused of ignoring the officially approved “programme, which suffered significant changes, especially in those cases when Noroc had tours beyond the republic’s borders.” Lucinschi does not fail to mention the “discontent” regarding Noroc’s “repertoire and behaviour” expressed in various letters sent to the Komsomol and local newspapers, invoking the public’s reaction as a legitimising strategy. The main grievance against Noroc and its musical style, in the Komsomol leader’s interpretation, concerns “the ethics of behaviour during the concerts and the quality of the repertoire.” In a revealing phrase deciphering these cryptic remarks, Lucinschi openly states that the band’s condemnation by the authorities derives from its “performances of musical pieces mainly authored by various English, French, Italian, and American Beatles” (sic!). This letter is also interesting due to Lucinschi’s parallel between Noroc and a similar Soviet musical group – the Leningrad-based band Poiushchie gitary (Singing Guitars), which also featured Western beat and rock music in its repertoire, coupled with modern arrangements of traditional Russian songs. Referring to a recent concert by the Poiushchie gitary held in Chișinău, Lucinschi hints at the danger represented by such musical trends, qualifying the Leningrad band’s music as “even more condemnable” that Noroc’s. This is due, on the one hand, to the “agitation among a certain part of our youth” (note the striking similarity to the language used by the letter from the Odessa party leadership). On the other hand, almost half of the songs performed during their concert “were borrowed from a different, foreign repertoire, completely alien to Soviet youth.” The real purpose of this letter becomes obvious from the seemingly innocuous conclusion, which states: “the republic’s youth is perplexed by the fact that this disbanded musical group was hired… by the Tambov Philharmonic orchestra and continues to tour the country… under its old name, Noroc.” The effect of this letter was immediate and radical: the members of Noroc were fired from the Tambov Orchestra and had to seek new employment in a small Ukrainian city. Lucinschi’s role in the whole affair was somewhat ambiguous: while playing the role of an ideological vigilante in December 1970, he was instrumental in assisting Noroc’s leader, Mihai Dolgan, to recreate the group under a new guise and name, Contemporanul (The Contemporary), in 1974. However, it is clear that Noroc’s deviation from the official ideological norms and its openness towards (and propagation of) Western musical trends were the real cause of the band’s demise. In an ironic twist, Lucinschi himself admitted, in a later interview, that the Noroc phenomenon became so popular due to its resonance with the wider youth subculture: “However hard the system tried, it could not control and curtail fashion, music, dances… i.e., the most elementary and necessary attributes of the young generation. Despite all the efforts made by the authorities, these things could not be stopped, because one simply could not stop the air we breathed. Two parallel worlds already existed in our society.” (Poiată 2013: 184).

The museum has several samizdat collections by Vasyl Stus, a poet, dissident, human rights activist and figurehead of the sixtiers movement. Two collected volumes of his poetry were given as gifts to Iryna Stasiv-Kalynets and her husband Ihor Kalynets, and later donated by Stasiv-Kalynets to the museum-memorial on Lonskogo St.

The first book Winter Trees (Zymovi Dereva) was published in 1969, and given to the couple on January 9, 1972. The volume included an inscription and in-text modifications written by Stus, which, in addition to providing insights into his creative process, also marked an important turning point in the story of these Ukrainian dissidents. Within a matter of days, Stus, Stasiv-Kalynets and many others were arrested in a sweep that took place on January 12-14, 1972. The catalyst was a “vertep,” or portable puppet theatre of the nativity scene accompanied by Ukrainian Christmas carols, organized by Lviv dissidents to draw attention to the plight of compatriots who had been arrested unjustly, like Valentyn Moroz in 1970, and to raise funds to support the families they left behind. Participants walked from house to house, dressed in colorful costumes and traditional Ukrainian clothing, carrying large festive stars and other adornments.

The carolers raised 250 karbovantsi (rubles) but 19 of the 45 participants were arrested and tried for anti-Soviet activities. Among them were Stasiv-Kalynets, sentenced to 6 years of hard labor and 3 years of exile, Stefania Shabatura, sentenced to 5 years of hard labor and 3 years of exile, and Vasyl Stus, sentenced to 5 years hard labor and two years of exile in Magadan. Stus was arrested again for anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda shortly after his release in 1979 and sentenced to another 10 years of hard labor. He died in Perm in 1985 after declaring a hunger strike to protest harsh conditions and his maltreatment at the hands of camp guards. Mykhailo Horyn’ was sentenced to 14 years of hard labor and exile, while Marian Hatala, an engineer charged with disseminating samizdat and other unsanctioned literature, took his own life.

The second volume, pictured above, The Merry Cemetery (Veselyi Tsvyntar), is also significant. As with the other book, we see Stus’ signature handwritten modifications. In the bottom left corner, there is also a stamp from the institute conducting forensic analysis for the courts. This stamp indicates that this volume was used as evidence of “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” Along with a collected volume by Mykola Kholodnyj titled Cry from the Grave (Kryk z Mohyly), this volume by Stus was confiscated in many apartment searches in 1972 and were used in multiple court cases against Ukrainian dissidents arrested that year, in particular, the artist Stefaniya Shabatura and samizdat publisher Ivan Hel’. These confiscated materials were returned to their original owners, Stasiv-Kalynets and Shabatura, after independence. Though their case files remain in the SBU archives, the material evidence taken from their apartments was returned.

The Architecture students’ Club A was a unique club in Communist Romania, a club in which it was possible to organise non-conformist concerts, shows, and debates that would immediately have been forbidden in communist Romania if the public had been allowed unrestricted access. Events organised at Club A were only open, however, to members of the club and their invited guests, only one per member, and membership was restricted to Architecture students. Consequently the Club A membership booklet had a value in itself. At the same time, the exclusivism of the club had a direct influence on the quality of the events organised there, as they became an alternative scale of recognition of the value and professionalism of the protagonists. The Mirel Leventer private collection contains a number of small objects indicating his membership of the Club A community in Bucharest, which respected with great care the criteria for inclusion in this exclusivist club. Among these insignia is his membership booklet, made like all such documents in the time of communism from pressed fabric; the date of issue is 1970. The cover of the booklet is light blue, and inside are presented all the privileges enjoyed by a member of Club A, together with the duties: free access to the club; the right to invite someone else once a week; participation in establishing the programme and at intervals in keeping order. These few rules made Club A a little exclusivist island, in which only a few could enjoy freedom. At the same time, these rules enabled the continuous functioning of the club until the fall of communism. It would immediately have been shut down if by accepting those who were not Architecture students its membership had grown rapidly and turned this exclusivist cultural experiment into a mass phenomenon. Finally, the collection also includes a Club A emblem made in ceramic and a number of badges: three from before 1989 and another three from after 1989. “What did it mean to be part of this world of Club A? It was something extraordinary in terms of social status. We were, if I may say so, in the student aristocracy. We were envied, very much envied. There were several attempts to close Club A; we were lucky, but we also had support, there, somewhere, higher up. Mac Popescu, he especially, managed to protect this institution where freedom was often exercised,” says Mirel Leventer.

The starting point of the work is the fluxus idea merging art and life: everybody is an artist.

A radicalized version of this idea appears on the tableau consisting of thirty-six panels: some of the photos present workers as representatives of different art forms (a working postman is identified as a mail artist, a turner is called a sculptor, a road-builder is called a land artist, a compositor is called a writer, a person sitting on the tram in dungarees an actor etc.).

The panels of this photo series are combined with press photos (identical in size) referring to new, often dramatic artistic roles (prisoner artist, fear artist, radical artist, hunger artist, despair artist etc.). The tableau is accompanied by a diagram, indicating that by 2150 everybody will be a police employee, and in 2240 everybody will be an artist.

(One may ask how a photo concept got into a collection focusing on painting? The reason is that it became a model: Ákos Birkás painted a picture in 1974 entitled Tamás Szentjóby: Aspects on the question: “Who is an artist?)A letter from Milan Uhde to the Host Publishing House in October 1970 shows him rejecting the report of his dismissal from work, the editorial office Host do domu. Uhde protested against the whole process, and rejected the term "agreement" in connection with the dismissal, then refused to sign a document on the termination of employment. Uhde also wrote about the non-existent opportunities to find other reasonable employment. The short letter documents practices of persecution towards important cultural figures criticising the post–August development in Czechoslovakia, as well as a concrete example of defiance towards them.

This manuscript entitled Istina o Jugoslaviji. Proživio sam dvadeset godina u komunističkoj Jugoslaviji. I. redakcija (The truth about Yugoslavia. I survived twenty years in communist Yugoslavia) was written in Padua in 1970, but printed in 1977 as a book in Croatian under the title Iza bodljikave žice: sudbina Hrvatske u srbokomunističkoj Jugoslaviji (Behind Barbed Wire: the Fate of Croatia in Serb-Communist Yugoslavia). In it, Čolak described his life before going into exile. He explained his life trajectory from the communist prison until the attempt to establish the first free review in Yugoslavia.