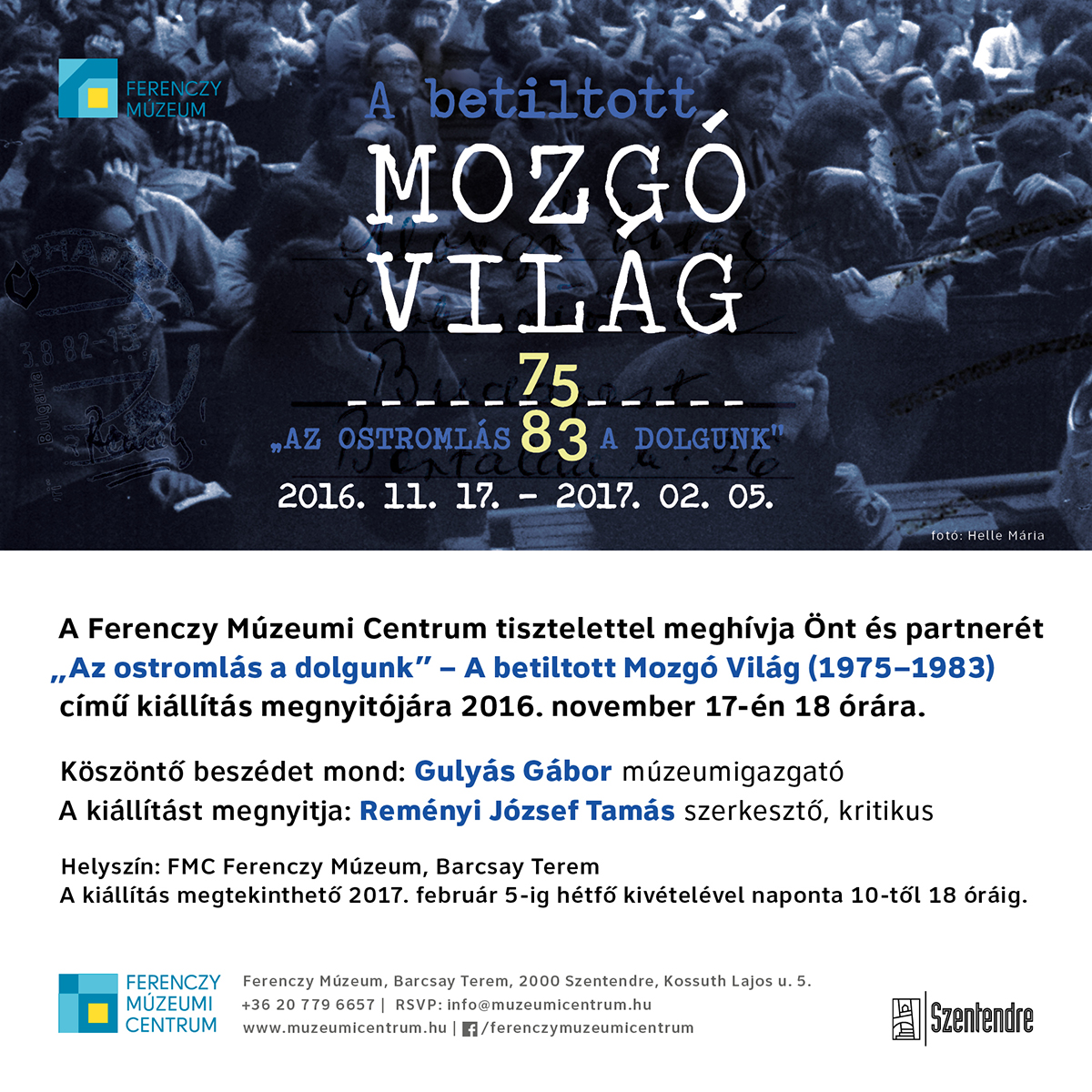

“The Prohibited Journal ‘World in Move,’ 1975–1983,” a temporary collection of the Ferenczy Museum in Szentendre, survived in two ways following the end of the exhibition. A selection of some digitalized sources can be visited on the Museum’s website (https://mozgovilagfmc.tumblr.com/), meanwhile the remaining part of the collection is stored in the archives of the Museum’s Literary Department. As for the website, it presents the main events of the journal and its authors and editors together with a series of documents, photos, and illustrations of contemporaneous art pieces. As for the archives, among the materials one can find the published and prohibited issues of the old “Moving World,” their one-time press coverage in gossizdat, samizdat, and tamizdat, the relevant reports by the one-time Communist secret police, and the archival photos of the main events in- and outside the editorial office (meetings, prize giving for the best authors of the year, readers’ club events) together with the printed material of the exhibition (invitation card, poster, catalogue, etc.).

By the 1960s a rather rigid and artificial network of state-financed literary periodicals emerged in Hungary, with the one and only literary weekly Élet és Irodalom (Life and Literature), two central organs (Kortárs – Contemporary; Új Írás – New Writing), and some two dozen monthlies, bi-monthlies, and quarterlies in the countryside. This setting clearly demonstrated that there was no space inside the monolithic system of communist cultural policy either for independent art and literary forums or engaged generational group formations. As for group formations, it was the young poets’ and writers’ main claim to their own literary paper since 1956 and for more than two decades, but all in vain. Although in 1969 the Central Committee of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP) promised to launch such a periodical, this was repeatedly postponed. Instead the Central Committee of the Communist Youth League (KISZ) in 1971 launched a rather modest series of anthologies for young poets and writers with the name “World in Move” (Mozgó Világ), with no more than half-a-dozen editions during the following five years. This loose series was transformed in 1975 into a bi-monthly, and from 1980 onward a monthly paper.

During the nine-year course of the old “World in Move” (1975–1983), there were 73 issues published as a common achievement of some two dozen editors and close to seven-hundred authors. By the late 1970s, the editorial office of the fresh, open-minded magazine – with high-standard intellectuality – became a real theoretical workshop as well as a popular meeting place for young Hungarian artists, writers, and intellectuals. The vivid and colorful character of the journal was comprised of not only its new and original belletristic publications together with some finely written critical reviews, but also a number of other columns, like those on film, theater, music, sociology, social theory, history, and journalism. The paper’s innovative spirit and interest in timely topics is well reflected in a number of exciting debates, e.g., on the role of experiment in arts and literature, on traditions, family, health care, and higher education reforms, and on national identity and the European heritage. The young authors and editors of the paper intended to break out of the “generational ghetto” by maintaining close contacts with some outstanding older writers with a high personal autonomy, critical sense, and other than Communist engagement – such as poet János Pilinszky, novelists Géza Ottlik and Miklós Mészöly, or the poet and essayist Sándor Csoóri. In parallel, the editors and authors of the journal made efforts to enlarge their contacts with intellectuals of the Hungarian minorities abroad, some Western emigre circles, as well as members of the democratic opposition in Hungary. From 1979, the editors and authors frequently held club meetings with their readers all over in the country in order to promote open dialogue with the public. These meetings became very popular among young intellectuals and students and took on the sign of solidarity and resistance as the journal became more and more involved in some scandalous conflicts as a target of party-state censorship. By early 1981 a deep crisis evolved. The Communist Youth League refused to print further issues of the paper, and a final prohibition seemed to be a serious risk. By then this was not at all the only ominous conflict: other recalcitrant cultural forums – such as the Hungarian Writers’ Association, the Attila József Circle of young writers, the periodical Tiszatáj, Béla Balázs Film Studio or the alternative theater formations – all had to face desperate fights for survival or to preserve their autonomy against the repeated attacks of party-state bureaucrats. However, none of these conflicts could make it more evident, than that of “Moving World,” that there was censorship in Hungary, even if the Communist leaders and apparatchiks tried to deny it in their public speeches. The journal managed to survive for three more years until late 1983, but in the end could not escape being shut down.

The old “World in Move” remained a symbol of cultural resistance and an alternative way of thinking. Looking back more than three decades later, the literary historian Éva Standeisky argues that “The editors and their supporters set an example of how independent-minded and creative intellectuals could and should practice their democratic rights publicly.”

Although a number of articles, interviews, and memoirs have been published about the banned journal ever since 1983, another 33 years had to pass before its rich documentary collection (prohibited issues, manuscripts, photos, art pieces, etc.) became publicly available in the retrospective exhibition of the Ferenczy Museum in Szentendre in late 2016 and early 2017. Some valuable parts of the resource collection have remained in the holdings of the Museum even after the exhibition ended, and a selection of digitalized documents is also shared with the public on the Museum’s website. There is also a significant set of new sources: curator Zsófia Szilágyi together with her assistants managed to complete an extensive oral history research project by making twenty video interviews with the authors and editors of the old “Moving World” as well as their supporters, the one-time activists of the student solidarity movement.