The Family of Clear Streams is still in existence and is the only known ecologically minded and art-focused commune in Serbia. In the words of Božidar Mandić, “The Family of Clear Streams is a small utopia. The opportunity for humankind is in small, rather than big utopias. Everyone should build their island of happiness and a better life, while avoiding totalitarianism as an inevitability of this world (capitalism, communism, techno-fascism).” (Milenković, 2015, p. 5) The commune is a meeting place and has been visited by thousands of people since its inception, who come for short or long stays. Most people visit the commune during the multiple-day, outdoor Šumes Festival of Alternative Theatre, an important event which first took place at the commune in 2002. Plays are spontaneously performed without prior announcement, making the event similar to a carnival.

The commune, “a small oasis”, never caught the attention of governing powers, nor was it targeted by pro-regime critique; hence and its ideas and principles have remained unaltered throughout the decades of its existence. The sole change which has occurred in the commune’s organization is that Božidar is currently its only member. “Life in the commune is in harmony with nature and natural light, it shifts the experience of time” says Milenković. There is an insistence on an infinite present, because “time is not at all passing, it only has its own density and/or rarity – all else is man’s subsequent projections and categorisations.” (Milenković, 2015, p. 63) There is no internet access in the commune, but television and radio are used at times.

Artistic performances are staged in the commune and also at festivals (e.g., Bitef in Belgrade and Infant in Novi Sad). The physical structures and rituals of the Family of Clear Streams are based on “The Search for the era of 5Es” (ecology, ethics, esthetics, erotica and emotions). Special relevance is given to maintaining a harmonious relationship between humans and the planet.

The commune today has only one permanent member, Božidar Mandić, while many others live there on occasion. The commune has many followers who hold particular ideals about dissolving the boundaries between living and art. Only three things are prohibited in the commune: meat, drugs and violence. Božidar grows organic food, lives a modest life and is occasionally paid honorariums via the related theatre group. He nurturers a child’s curiosity, which he makes use of in his theatrical work. In his own words “the theatre of the Family of Clear Streams is a theatre of energy”. “The fundamental medium and theatrical object in Mandić's plays is the human body, which onstage displays its instincts, frustrations, sufferings, anxieties, eroticism, aggression, excitement, happiness or misfortune, hope, sexuality…” (Milenković, 2015, p. 71, 75) Božidar directs his plays, which are mostly nonverbal, and they are performed differently on every occasion since they are not based on strictly binding rules but, essentially, on free self-expression. His art is based on errors and he rejects ideas about perfection or ‘perfect artwork’, because, in the end, these ideas lead to indifference.

The BACK – Božidar Mandić and The Family of Clear Streams (1969 – 2015) exhibition is a unique portrayal of the long-standing, diligent and continuous work of the artist Božidar Mandić. After his involvement in Youth Tribune and the resulting pressure rendering his free artistic expression in Novi Sad impossible, Božidar established the Family of Clear Streams commune where he has continued to pursue his artistic and social ideas. The exhibition gave place to numerous works of art created in the commune, which are inseparable from its principles, as well as photo documentation of life in the commune.

Discussing the period when Božidar began his artistic practice, Nebojša Milenković, author and curator of the exhibition, told COURAGE: “Art was not limited to developing [artistic] concepts and carrying out performances, it was the very atmosphere of rebellion and noncompliance that developed between guys from the Youth Tribune, as well as their exploration of [social] alternatives. 1968 was a great [moment of] nonconformance of the youth with the state of the society they lived in, but it was not the same in France, New York or in former socialist countries.”

The artists who pursued these ideas and lived and made art in Novi Sad, found a welcoming venue in the Youth Tribune, but only for short span of time: “After the experience of short-lived ghettoes of free thought, a media and political campaign (from 1969 to 1973) was set in motion, lasting for years, the end result of which was the disciplining of those of the Youth Tribune, the sacking of its program directors, as well as the editors of youth periodicals sympathetic to New Art, the arrests of Miroslav Mandić, Slavko Bogdanović, and Ottó Tolnai and the social marginalization and existential problems that many of them have been unable to overcome up to the present day.” (Milenković, 2012, p. 19)

Explaining the methods used in that process, Milenković claims that artists associated with Youth Tribune were persecuted by other artists and so-called ‘well-meaning citizens’, and harassed by intellectuals with close ties to the regime and by media which fueled the prosecution. Subsequently the (communist) party took action.

“It can be said that creating artwork (or documenting it) was of less significance – because fidelity to the new spirit of art was expressed by permanent socializing, playing football, ‘corner-cruising’ (ćoškarenje, a term invented by Slobodan Tišma), drinking Coca Cola or kvass in front of corner shops in Liman, going to concerts or out into nature, bathing together on Oficirac beach...” (Milenković, 2015, p. 11)

The members of this art scene and the curator and author of the exhibition share the notion that “the most thorough material for interpretation and historic evaluation of the 1970s art scene in Novi Sad is kept in the archives of the local police, which directly or with the help of informants kept precise evidence of their artistic activities.” (Milenković, 2015, p. 12) The newspaper Dnevnik in Novi Sad another source, since they published detailed reports of these artistic actions described as “harmful to society”.

Following their disengagement from Youth Tribune, the artists transformed their praxis: Miroslav Mandić refrained from publicly displaying his art; Slobodan Tišma practiced ‘invisible art’; Božidar Mandić retreated to the forest; others chose to pursue completely different careers. In Nebojša Milenković’s interpretation, “that was the moment when Novi Sad culture chose not to be a dynamic but a static culture and has remained so ever since. It is a culture which does not promote alternatives, which accepts the existing, which does not pose questions.”

This turn of events led Božidar Mandić, one of the most prolific members of Youth Tribune, to the idea which was to leave a lasting mark on his subsequent art and way of life: “This idea is sublimed in the statement: The avantgarde has to move in reverse!” (Milenković, 2015, p. 35)

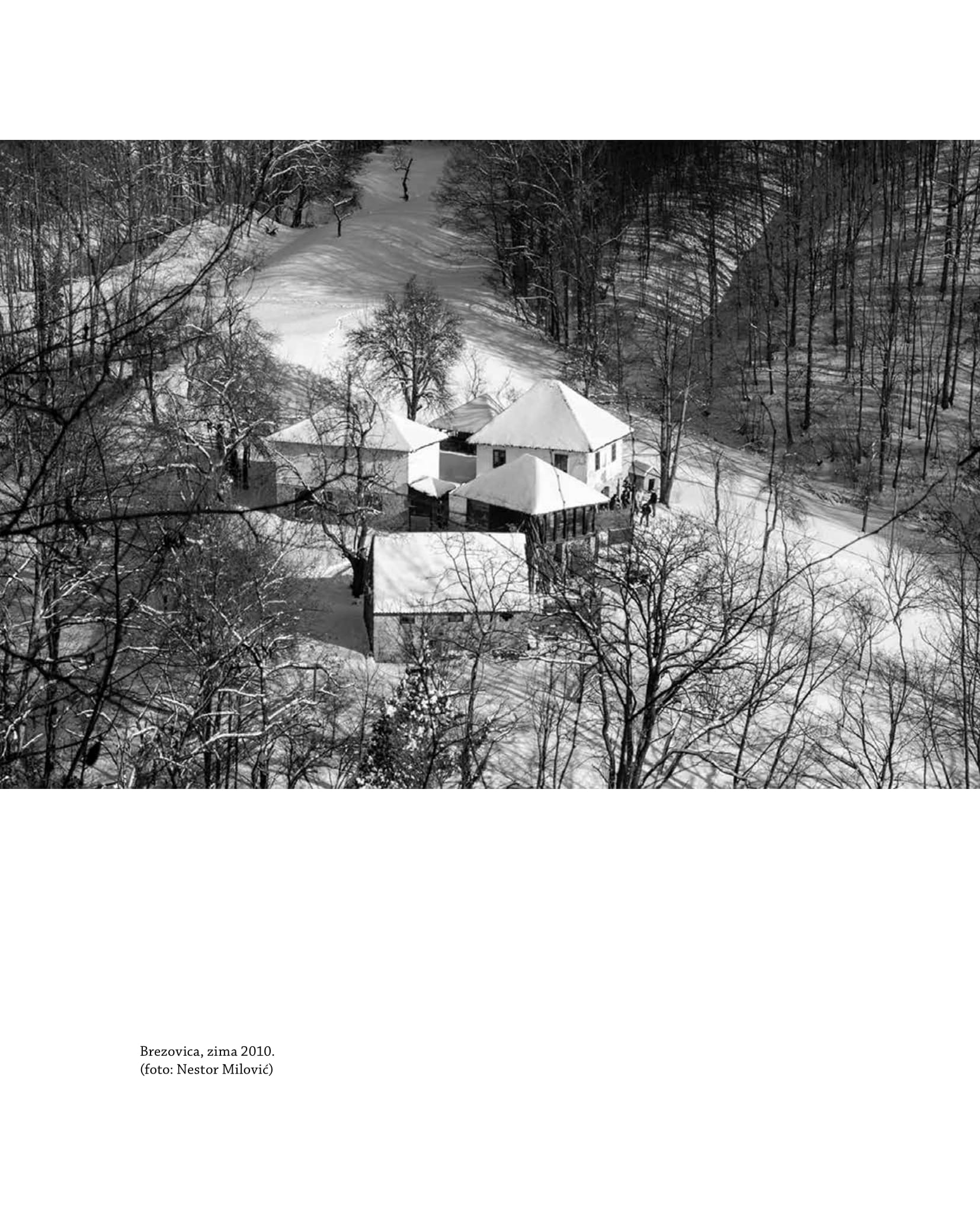

In 1977 Mandić moved to the village Brezovica at the foot of Rudnik mountain together with his spouse Braila and newborn daughter Ista and started setting up the Family of Clear Streams commune. There, the Mandić family had two more children, Sun and Aja, and child raising and education are given great importance within the commune. The author and curator of the exhibition explains that “art is also the way in which Božidar brings up his children and teaches them to be good people, to respect each other and nature, and that is a contribution to society”. They nurture the idea that people have to return to elementary culture, like closeness to soil, farming and consuming self-produced food. The principles of the commune are the “Philosophy of Soil”, “Open Home”, “Poor Economy” and “Art”.