The Gheorghe Leahu Collection portrays the activity of an architect who, out of the desire to escape the ideological constraints imposed on his profession during the communist period, painted numerous watercolours representing urban landscapes in Romania, old streets and buildings, especially in Bucharest, many of which were destroyed by the “urban systematisation” policy of Ceauşescu’s regime.

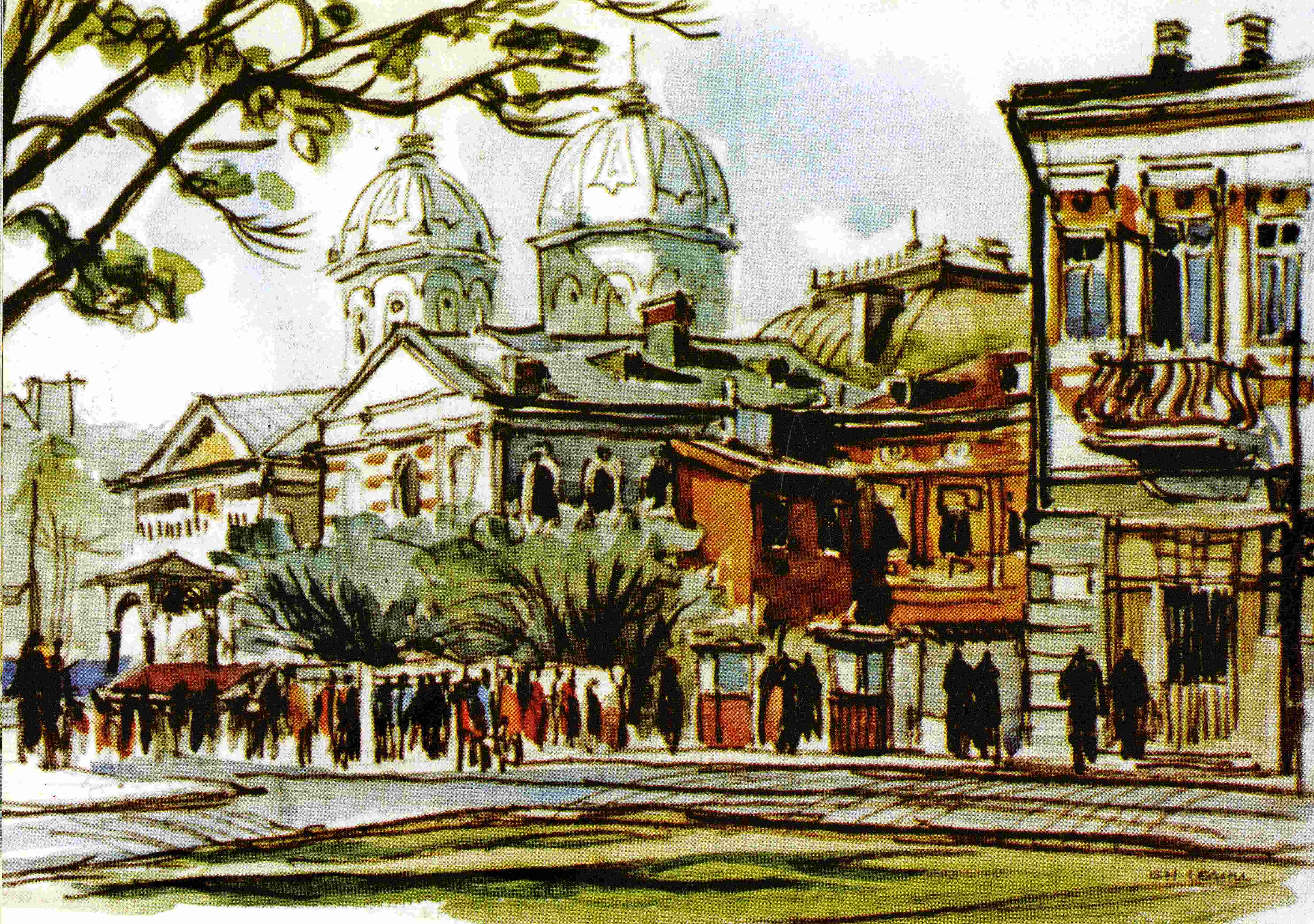

The Gheorghe Leahu Collection is made up of two parts, given the historical context in which the pieces were created or collected. The first part of the collection contains watercolours, drawings, photographs, letters, and books from the communist period. Leahu painted his first watercolours while he was in high school (1948–1951). He continued to paint during his university years and after he started working in 1957 at Bucharest Project Institute (Institutul Proiect Bucureşti), the state company in charge of carrying out urban planning and architectural projects in the capital of Romania. The watercolours gradually became an escape from the daily stress of practising architecture in an institutional system in which the professional activity of architects was marked by brutal interference on the part of the authorities. In the 1980s, when these interventions by the holders of political power became increasingly arbitrary, watercolours represented for Leahu a space of creation, where he was free to choose his topics and the manner in which to approach them. The watercolours which depict streets and monuments in the centre of Bucharest, destroyed by the so-called “urban systematisation” policy of Ceauşescu’s regime, are also important sources of information on the architectural heritage which the communist authorities considered obsolete enough to let it be erased. According to Leahu’s account, he painted the watercolours, which he thought of as “architectural watercolours,” because he wanted to capture for posterity the beautiful and picturesque old city centre which was vanishing away. An album containing a selection of these watercolours was sent in 1986 to a publishing house specialising mainly in books related to leisure-time activities, Editura Sport Turism, which initially approved its publication under the title: Bucureşti – arhitectură şi culoare (Bucharest – Architecture and Colour). However, after it was published in 1988, the album was withdrawn before reaching the bookshops and destroyed. The reason was that the volume included watercolours of many old churches considered historic monuments, and remembering them contradicted the policy of the regime concerning the urban restructuring of the capital. This restructuring actually entailed the demolition of numerous historic monuments of Bucharest, even of entire areas of the old centre, in order to make room for a new socialist centre to reflect the greatness of what the state propaganda presented as a “Golden Age” (Panaitescu 2012). In the particular cases of the old churches, the process of “urban systematisation,” as applied in Romania’s capital city, implied either their demolition, as in the cases of Sfânta Vineri (Saint Friday) Church or Văcărești Monastery, or their translation to a different and less visible position, usually behind newly constructed blocks of flats. The latter required a very complicated and actually ingenious engineering process, as was accomplished in the case of the Mihai Vodă Church, an architectural emblem of historical Bucharest. The entire process was legitimised by the discourse constructed around the concept of “urban systematisation,” which presented demolitions as a necessary step in modernising the city.

The manuscripts and letters from the communist period reflect the ideological constraints aggravated by the adoption of the so-called “July 1971 Theses” and the development of Ceauşescu’s personality cult, as well as by the severe shortage of basic products which affected Romania in the 1980s. The “July 1971 Theses” represent a programmatic document through which Ceauşescu intensified the Party’s control over cultural activities and brought back cultural practices characteristic of the Stalinist period. Among the manuscripts, an item of considerable documentary value is the diary written in secret in the period from 1985 to 1989, and published in 2013 by the Civic Academy Foundation under the title Arhitect în “Epoca de Aur” (Architect in the “Golden Age”), which includes harsh criticism of Ceauşescu’s regime and policies.

The second part of the collection, created after 1989, includes watercolours, drawings, manuscripts of certain papers or communications, brochures and concepts of exhibitions, photographs, and books. These materials reflect Leahu’s activity in post-communism and the way his watercolour collection was put to use. After 1989, Leahu organised many exhibitions in which he displayed his watercolours, both in Romania and abroad (New York – 1992, Vienna – 1994, Chicago – 1995, Paris – 2001, Venice – 2002). The watercolours which represent the old centre of Bucharest were reproduced in a series of albums such as: Lipscani – centrul istoric al Bucureştilor (Lipscani – the Historic Centre of Bucharest, 1993), Bucureştiul dispărut (Lost Bucharest, 1995) and Distrugerea Mănăstirii Văcăreşti (The Destruction of the Văcăreşti Monastery, 1997). At the exhibitions, the architect Leahu donated or sold around 150 watercolours, out of the over 800 watercolours he painted. The other watercolours remained in the painter’s possession.

The Gheorghe Leahu Collection, especially the watercolours and the diary, represents an alternative visual memory to that promoted by the official discourse of the 1980s, which depicted the “Golden Age” as a period of grandiose constructions but kept silent about the destruction of many heritage edifices in Bucharest. This alternative visual culture was manifest in the 1980s through the attempts of those who appreciated the architectural heritage of Bucharest to rescue in various ways the memory of the destroyed streets and buildings, with the help of paintings, drawings, and photographs. This alternative visual culture, which surfaced after 1989, became an essential component of the public discourse about Bucharest and its transformations in various period, in the form of nostalgia for the lost parts of the city.