Among the files created by the Securitate that reflect oppositional activities against the communist regime in Romania, a significant number concern the activity of various religious denominations. This proportion reflects the fact that it was within religious denominations that the most coherent and consistent oppositional milieus existed, which were perpetuated throughout the entire communist period and suffered harsh repression.

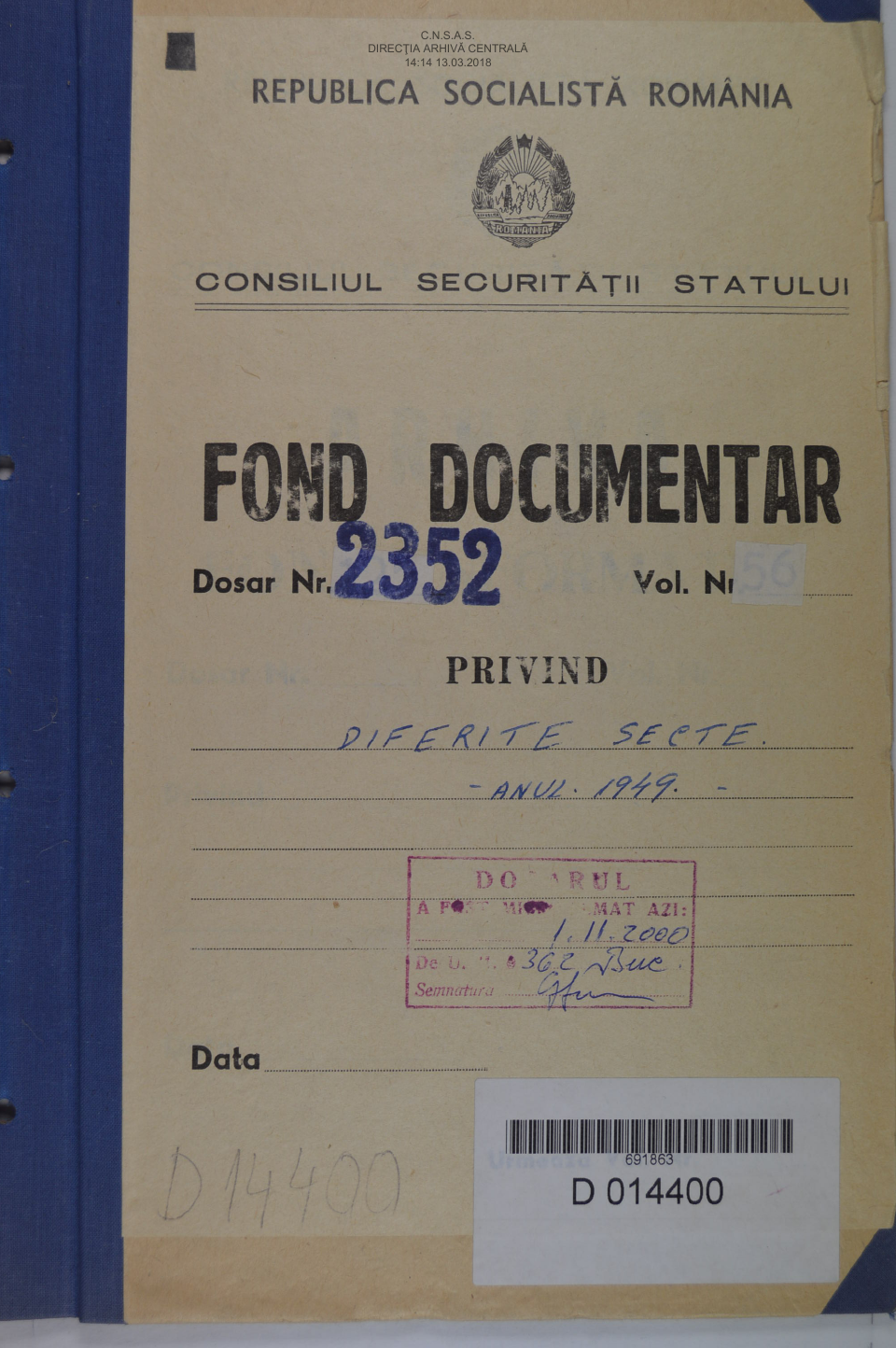

Due to the fact that a large variety of religious activities were subjected to both attentive surveillance and harsh repression, the files created by the Securitate on this issue are very diverse. The most complex files regarding acts of opposition to the communist regime coming from religious denominations are to be found within the files of the Documentary Fonds (Fond Documentar), which either concern only one religious denomination or deal with acts of religious dissent from different religious denominations. The creation of these files reflects the way the Securitate carried out its policies and conceived its areas of activity when dealing with religious denominations. These files comprise: orders and detailed instructions of the central headquarters or the regional headquarters (replaced in the late 1960s by county inspectorates) of the Securitate, circular letters of various headquarters of the secret police, reports of its local branches addressed to central or regional directorates concerning a specific area of activity, statistics and other quantitative analyses concerning those persons under surveillance or under arrest by the Securitate in relation to to a specific area of activity, called in the Securitate’s officialese an “issue” (problemă), original documents or copies of documents confiscated or intercepted by the Securitate, duplicates or copies of informative notes, personal sheets synthesising information about key persons connected with an issue, photographs, duplicates of documents from other kinds of files such as “informative surveillance files” (dosare de urmărire informativă) or “criminal files” (dosare penale) etc. The files of the Documentary Fonds are an invaluable source for understanding how the secret police perceived a religious denomination and what policies were carried out in order to gather information, penetrate with informers or repress a religious group. The way these files of the Documentary Fond are structured mirrors also how the Securitate was organised in different periods. After the reorganisation of the Securitate in the period 1968–1969, following the new national administrative division, the Securitate created archivist departments in all its county inspectorates. Consequently, all these inspectorates produced their own documentary fonds regarding all key areas of activity at the local level. Besides these files created by the county inspectorates, a significant number of files of the Documentary Fonds were created by the central headquarters or archived by it. This second category of files of the Documentary Fonds is now to be found in the CNSAS archives (the institution with custody of the files since 2000) under the title: “Bucharest Documentary Fonds” (Fond Documentar Bucureşti).

A second main category of the Securitate files regarding religious dissent in communist Romania is made up of the so-called “informative surveillance files” (dosare de urmărire informativă). These files are the result of the operative activity of the Securitate carried out in order to keep a person or a group of persons under surveillance. According to the kind of “subversive” activity carried out by the person under surveillance, the person in question was integrated into a so-called “issue” (problemă), in fact an area of activity. Each area of activity also received a numeric code, which was inserted in the informative surveillance file (Petcu 2005, 125–126). The code was used in order to more easily categorise that file in terms of the main areas of activity of the Securitate. Informative surveillance files were considered the reflection of the most complex form of surveillance. Consequently, these files gathered a large diversity of documents such as: motivated requests for the opening of the informative surveillance file, drafted by the local branch of the Securitate; detailed plans of the surveillance activity; reports on the surveillance activity; instructions from the Securitate’s headquarters; notes from informers; diagrams showing the social network of the person under surveillance; photographs; intercepted documents (such as letters and manuscripts); transcriptions of recorded private conversations. In contrast to the first category of files, which are focused on a category of persons gathered under a so-called “issue,” files of this kind are mostly focused on individuals and their social networks.

The third category of files of this collection, the so-called “criminal files” concerns those persons arrested and investigated by the Securitate due to their religious beliefs. It is impossible to establish the number of “informative surveillance files” or “criminal files” created on the persons kept under surveillance or investigated by the secret police specifically for their religious convictions. One reason for this situation is the intertwined character of many files, which included not only religious dissent but also political dissent or other forms of opposition. Although the first two categories of files include also documents with religious content confiscated or intercepted by the secret police, the greatest quantity of such documents is to be found in the criminal files of those arrested for their religious activity. In order to document and prove their accusations, the Securitate attached the confiscated religious materials to these files, which were made use of by the state prosecutors during the trials. As in other cases of artefacts concerning opposition to the communist regime archived by the Securitate, by collecting religious material for its own purposes, the Securitate archives became paradoxically a custodian institution of cultural opposition. The files of this collection comprise many kinds of religious artefacts or duplicates of manuscripts which were destroyed by their owners under communism due to the risk of being captured.

The secret police put under surveillance and repressed persons and groups from various religious denominations, both from officially recognised ones and from those labeled by the state authorities as “sects” or “anarchic groups.” It should be mentioned that the official religious denominations were treated differently from one case to another and the state policies towards an official denomination also changed from one period to another.

The manner in which the communist state authorities approached a religious denomination was influenced by several factors: 1. whether it was an officially recognised denomination or not; 2. the extent to which the leadership of the denomination was open to negotiating for official status by making comprises with the state authorities; 3. its foreign contacts, especially if a denomination was subordinated to a centre located in the West; 4. the practice of proselytic activity outside the community; 5. the organisation of religious meetings in private dwellings or in other spaces unauthorised by the state authorities; and 6. the underground printing and circulation of religious publications.

Taking into account these aspects, the communist regime divided religious groups into three main categories: the “official denominations”, the so-called “sects”, and the so-called “anarchist groups.” Besides what the state authorities called “historical churches” (Muntean 2005, 92), which at the moment when communist regime seized power had already been recognised as official denominations, the new regime granted official status in 1948 to another four religious denominations that previously had been mostly labelled as “sects” by official discourse: the Baptist Christian Church, the Seventh Day Adventist Church, the Christian Evangelical Church of Romania (Cultul Creştin după Evanghelie din România, which is a Plymouth Brethren protestant denomination) and the Pentecostal Church. Other religious minorities that failed to receive official recognition continued to be labelled as “sects” or “anarchist groups” (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu and Vasile 2007, 466). All the religious minorities labelled as “sects” or “anarchist groups” were outlawed (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu, and Vasile 2007, 466–467). Those groups from the first category (“sects”), including among others the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Nazarenes and the Seventh Day Adventist Reform Movement, became the target of harsh repression immediately after the regime consolidated its power in 1948. For example, according to internal records of the Jehovah’s Witnesses organisation, only between 1951 and 1953, 800 Jehovah’s Witnesses were arrested out of the 15,000 members this religious minority had in Romania in 1949 (Ioniţă 2008, 216֪–217). The so-called “anarchist groups” comprised factions or radical groups that emerged from within some of the official denominations such as the the “Lord’s Army” (Oastea Domnului) within the Romanian Orthodox Church, the dissident group inside the Pentecostal Church, or the “Bethanists” (Betaniştii) within the Reformed Church (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu and Vasile 2007, 466–467). The Lord’s Army was an “evangelical awakening” within the Romanian Orthodox Church initiated in 1923 by the Transylvanian Orthodox priest Iosif Trifa, who was defrocked in 1936 due to his disputes with Metropolitan of Transylvania Nicolae Bălan (Ramet 1992, 193). The movement was heavily repressed by the state authorities and its leaders imprisoned under communism.

Although those religious minorities placed outside official recognition suffered heavily from the repressive measures of the communist authorities, persons and large groups among the official denominations were also victims of state repression for their religious activities. For example, in the case of the Romanian Orthodox Church many monasteries, such as those of Vladimirești and Sihastru (both in the Southern part of Moldavia) were accused by the state authorities of being centres of “religious mysticism” and their religious communities repressed in the 1950s (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu and Vasile 2007, 461). The Orthodox priest and professor at the Theological Institute in Bucharest Gheorghe Calciu Dumitreasa was the main Orthodox religious dissident during the 1970s and 1980s. For opposing the demolition of the Enei Church in Bucharest in 1977 and for his criticism of anti-religious state policies in his sermons, he was imprisoned and was defrocked by the Romanian Orthodox Church (Calciu-Dumitreasa 2001).

The Roman Catholic Church was a “tolerated church with a beheaded hierarchy,” given that “the prelates Márton Áron, Anton Durcovici, Alexandru Cisar, Hieronymus Menges, Augustin Pacha, János Scheffler, Joseph Schubert, Ioan Duma and Adalbert Boros were either arrested or placed under house arrest” (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu and Vasile 2007, 464). A special case was the Romanian Greek Catholic (Uniate) Church, the only official religious denomination suppressed by the communist regime in December 1948, of which not only the hierarchy but also more than 400 priests were imprisoned (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu and Vasile 2007, 463). The collection of documents confiscated by the Securitate from members of this Church or issued by the secret police in order to repress it or keep it under surveillance is presented on this website (See: Romanian Greek Catholic Church Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS).

Many protestant or what the communist regime called “neo-protestant” believers stood out as fighters for religious freedom in Romania. Among the most renowned cases are Richard Wurmbrand, Ferenc Visky, Simion Cure, Vasile Moisescu, Gheorghe Mladin, Traian Ban, Simion Moţ, Teodor Băbuţ, Nicolae Todor and Alexandru Honciuc (Tismăneanu, Dobrincu, and Vasile 2007, 463). In the context of the signing by Ceaușescu’s Romania of the Helsinki Final Act in 1975, a group of ministers from the Baptist Church, the Christian Evangelical Church of Romania and the Pentecostal Church drafted and signed an open letter of protest against the infringements of human rights by the Ceaușescu regime regarding the members of the their religious denominations entitled: “The neo-protestant denominations and human rights in Romania”. The letter was sent to Radio Free Europe and broadcasted in April 1977 (Dobrincu 2012, 351–402).

A significant number of the files of this ad-hoc collection, especially those pertaining to the Documentary Fonds, were created by those branches of the Securitate in charge of dealing with religious denominations. In July 1948, when the Securitate was officially created (the institution was entitled: General Directorate of the People’s Security – or DGSP after its Romanian acronym), its 1st Directorate (after July 1956 renamed the 3rd Directorate) included a special department entitled “Nationalists, Churches and Sects” (Serviciul Naţionalişti, Culte şi Secte).

This department was in charge of carrying out operations targeting national (ethnic) minorities, official churches and various religious minorities (many of them labelled as “sects”). This department included various working units (birouri), each of them specialised in an area of activity called an “issue.” For example, in July 1948, the first working unit was in charge of keeping under surveillance and repressing those hostile groups within the Romanian Orthodox Church, the second unit dealt with the Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic Churches, and the third was in charge of the official protestant churches and of those religious minorities labelled in the official discourse as “neo-protestant denominations” (Oprea 2003). The same structure was also to be found at the level of the regional directorates. The activity of these local working units was coordinated by the corresponding working units at the central headquarters of the Securitate.

Most of the files pertaining to the Documentary Fond, but also a significant number of “informative surveillance files” and “criminal files” regarding the activities of religious dissent of various religious denominations have been accessed by researchers or victims of the secret police. The research activity conducted by historians, theologians, sociologist, anthropologists and journalists has resulted in the production of a large body of monographs, articles or edited volumes of documents concerning religious dissent and its persecution under communism. From this perspective, it may be said that some of the most researched files in the Securitate archives are those relating to the activity of religious denominations.