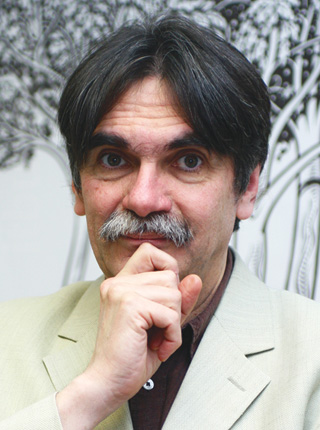

András Török was born as a single child of a middle-class family in Buda. His family tried to avoid confrontations with the regime. He studied English, Greek, and History at the Eötvös Loránd University of Budapest (ELTE), where he completed his degree in the mid-1970s. He worked as a translator and designed booklets for the National Theatre and the József Katona Theatre at the turn of the decade. In the 1980s, he published books on Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde, and in 1989 he was one of the founding editors of the journal 2000, which was a major cultural journal in Hungary after the regime change.

Török considers himself a secondary figure in the democratic opposition of the 1980s. He became acquainted with the opposition through his female contacts. Miklós Haraszti was Török’s first wife’s brother-in-law. Török started to attend events with his first wife and Haraszti, but he also spent a lot of time in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, which was a kind of “headquarters” for some of the leading figures of dissidence. He became directly involved in oppositional activities when philosopher János Kis approached him in the library and asked him to sign the famous letter to the first secretary of the Party, János Kádár, in 1979. The letter called upon Kádár to act against the persecution of the Czechoslovak Charter 77 signees and prevent political trials in the Eastern Bloc. Török decided to sign the letter, as he enjoyed being part of the alternative scene. As he pointed out in his interview with COURAGE, this act was a turning point in his life. It was a liberating experience for him that gave him a sense of relief.

As Török recalled, he was in a privileged position, as he could earn money teaching English, which was a well-paid form of employment under late Socialism. He gave English courses for firms which let him spend a large part of his day in the library reading and writing non-fiction. He was, therefore, relatively independent and felt less pressure from the state than others who had ordinary jobs. He did not want to go abroad: he never applied for a passport, so he did not test the system in this respect. One of the reasons why he enjoyed being close to the core of the democratic opposition, though, was that it gave him the chance to make the acquaintance of foreign intellectuals and artists, which was a kind of substitute for trips abroad.

In the mid-1980s, János Kenedi made him part of the editorship of the samizdat journal Máshonnan Beszélő (Speaking from Another Stance). He coordinated the work of translators and proofread the texts. He regarded this as very normal activity. It somehow seemed obvious to him that people like him would be engaged in such things. He never felt the urge, though, to document this activity. He did not put anything aside for preservation, nor were people encouraged by leaders of the opposition to do anything of the kind at the time. He was told that, in case of a police raid, he should say that he had found the materials that happened to be confiscated from him in a telephone booth on the street. According to Török, he himself never suffered any negative consequences for being part of the democratic opposition.

Török has made very clear his love of the city of Budapest on many occasions, and he is the author of the bestseller Budapest: A Critical Guide. He has always been irritated that old images of Budapest are difficult to access in museums and it costs a lot to have reprints made. He was charmed by Fortepan from the outset, as it contains many photos that were taken in Budapest. Summa Artium supported the launch of Fortepan financially, and Török occasionally brought photos to the collection, but legal cooperation only began in 2014. Fortepan signed an agreement with Summa Artium according to which the latter would handle its financial issues, secure the photos and equipment, and legally represent Fortepan. Miklós Tamási, the founder of Fortepan, is now employed by Summa Artium.

András Török was in a position to exert a decisive influence on memory politics as undersecretary of culture in 1994–1995 and president of the National Cultural Fund from 1996 to 1998. As he recalled, his term in office made clear to him that it would be difficult to harmonize his ideals and the actual practice of politics, and this was a major disappointment for him. He always imagined that the Dutch model of cultural politics, of which he is particularly fond, could be imported to Hungary, but the legacy of socialism, among other factors, prevented this. In his view, a large part of the Hungarian intelligentsia was not and is not prepared to live in an uncertain world, and members of the Hungarian intelligentsia are often all too willing to subordinate themselves to political interests in order to avoid competition and create a safe zone. From 1998 to 2003, he was the director of the Mai Manó House – The Hungarian House of Photographers. In 2004, he became the director of Summa Artium Foundation.