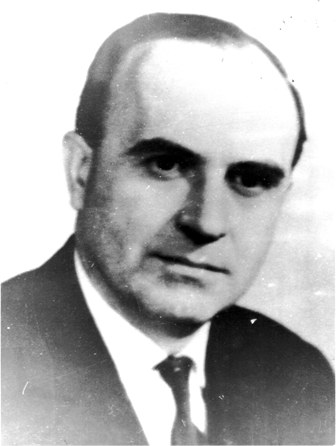

Cornel Irimie (born 17 January 1919, Sibiu – died 22 March 1983, Sibiu) was a Romanian sociologist, ethnologist, and museologist who in 1963 established the Museum of Folk Technics (Muzeul Tehnicii Populare) in Sibiu, which was later renamed the ASTRA National Museum Complex (Complexul Naţional Muzeal ASTRA or, in short, Muzeul ASTRA). He is also known for his extensive ethnographic research, which he conducted from the 1950s to the 1970s mainly in Transylvanian villages. Irimie was born in a family with peasant roots in southern Transylvania. After graduating from high-school in Sighişoara in 1937, he chose to study rural sociology and ethnography at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy of the University of Bucharest. He was a disciple of the Romanian sociologist Dimitrie Gusti, considered the creator of the school of sociology at the University of Bucharest in the interwar period. In the period 1938–1940, he took part together with Gusti in field research that gave him the opportunity to assimilate the methods of monographic research. As defined by Gusti, the methodology of monographic research includes the multi-disciplinary approach of a “special unit” through field research conducted by mixed teams consisting of sociologists, geographers, historians, linguists, economists, folklore collectors, and physicians. Given Gusti’s appreciation of Irimie, the latter was included as a student in his team at the Institute for Social Research of Romania (Institutul de cercetări sociale al României), where he worked as a researcher from 1938 to 1940. On Gusti’s recommendation, he received a doctoral scholarship at the University of Jena (Germany) where he studied between 1941 and 1943. This scholarship prevented him from participating, alongside most of Gusti's disciples, in field research in Soviet Transnistria while it was occupied by Romanian troops during the Second World War. He finished his doctoral studies in 1948 after defending his dissertation entitled “Inter-village Social Relations in the Olt Land” (Relaţiile sociale intersăteşti din Ţara Oltului) coordinated by Professor Gusti at the University of Bucharest.

However, during the communist period, Irimie concealed his close association with Gusti, who had been purged from the university, as well as his former sympathies for the extreme right party of the Legion of the Archangel Michael. This camouflage was possible because, given his young age in 1938–44, Irimie had not held any key position in the government apparatus of the right-wing dictatorships that had succeeded each other in this period in Romania. In comparison, other Romanian sociologists who had been active in the interwar period had a different fate regardless of their political orientation. For instance, the left-oriented Anton Golopenţia and the enthusiastic supporter of the Romanian extreme right Traian Herseni, who had both been active in the sociological campaign in Soviet Transnistria, were both purged and arrested; the former died while imprisoned, while the latter spent years in prison before being released. In contrast, Irimie was hired in 1945 by the Ministry of Arts as an abstractor for matters pertaining to the rural world, and later, in 1952–1953, acted as head of the folk art section at the Decorativa factory in Bucharest. In 1953, he moved back to his native town of Sibiu, where he was hired as an assistant researcher at the Brukenthal Museum, one of Romania’s most prestigious art museums. Irimie’s departure from Bucharest also helped him to break with a problematic past, including his association with Gusti’s sociological school and his former sympathies for the Legion of the Archangel Michael. At the Brukenthal Museum, he steadily climbed the hierarchical ladder. He became a researcher in 1955, head of section a year later, assistant scientific director in 1967, and finally director of the Museum in 1969. His research activity was held in high regard by research institutions in communist Romania. From 1956, Irimie acted in parallel with his position at the Brukenthal Museum as a researcher at the Romanian Academy’s Centre for Social Studies in Sibiu and as a collaborator of the Academy’s Institute for Art History. In 1969, after the establishment of the Sibiu division of Babeş–Bolyai University in Cluj, he became a Senior Lecturer at its Faculty of History and Philology, where he lectured in ethnography and museum studies from 1969 to 1973. The leading positions Irimie held at cultural institutions in Sibiu and the authority he enjoyed within the regime’s academic structures allowed him to conduct research that was apparently incompatible with the official cultural policies. More precisely, throughout the 1960s, Irimie carried out field ethnographic work on religious practices among rural communities in Transylvania, acquired icons on glass for the Brukenthal Museum, and wrote studies on the art of painting icons on glass. Some of these studies were able to be published at the end of the 1960s in the context of the relative cultural liberalisation that occurred during the first years of the Ceauşescu regime.

Irimie’s major achievement, however, was the establishment of the Museum of Folk Technics in Sibiu in 1963 as a division of the Brukenthal Museum. The support he received from the local and central authorities for opening an ethnographic museum in Sibiu, for which they granted a large piece of land on the outskirts of the city, indicates that Irimie was definitely not in conflict with the regime, but rather capable of taking advantage of the ideological changes in order to consolidate his professional career. His national and international academic prestige in a field like ethnography and folklore, which had become instrumental for the nationalist propaganda of the Romanian communist regime, must have contributed to the privileged relations he maintained with the local and central authorities. Nonetheless, according to his son Radu Nicolae Irimie, he was kept throughout his life under the attentive surveillance of the Securitate, which is not surprising given the problematic past that he tried hard to conceal. At the same time, Irimie was allowed to hold leading positions in internationally visible Romanian cultural institutions, which indicates that he was ultimately a person who acted in the space between tolerated and supported.

The Museum of Folk Technics was in fact a museum of Romanian rural civilisation conceived according to the ideas of Gusti and his sociological school. The establishment of this open-air museum meant that many artefacts of Romanian rural civilisation, such as traditional houses, mills, tools, and peasant home interiors, which would have otherwise been destroyed by the communist regime’s rapid modernisation of agriculture and villages, could be rescued and exhibited there. Irimie tirelessly supported the acquisition of many religious artefacts such as icons, triptychs, and crosses. Even though they were not exhibited during the communist regime, Irimie acquired them, thus running the risk of being sacked from the institution. In addition, under his coordination, the employees of the Museum of Folk Technics were also able to conduct field research on religious customs and beliefs in villages. The research findings can be found in the archival collections of the ASTRA Museum.