“The only live tradition of Hungarian alternative political thinking today is that of István Bibó,” said historian Miklós Szabó, a prominent theorist of democratic opposition at the beginning of his review of the Bibó memorial book, published in the first issue of Beszélő (Speaker), a prominent Hungarian samizdat periodical launched in December 1981. As Szabó argues a few lines below, “in the 1970s, there was a real Bibó revival in Hungary; his earlier studies were copied and distributed in samizdat and then discussed by many young intellectuals, and they found new devoted readers even among people who otherwise rarely read similar sources of alternative thinking. (…) Now, the Bibó Memorial Book represents a conscious and intended culmination of this unique revival.”

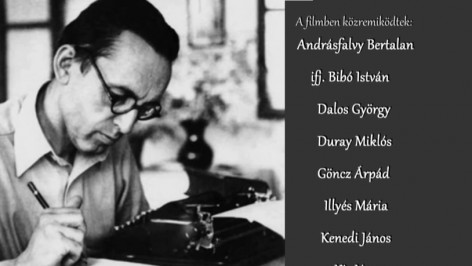

In early 1979, at the initiative of János Kenedi, a voluntary editorial team of intellectuals was formed to prepare a tribute anthology on the occasion of István Bibó’s 70th birthday. However, as Bibó died in May 1979, the book became something of a post mortem homage, as it was published a year later in a samizdat edition. (Bibó’s funeral developed into a silent protest demonstration against the communist regime, as thousands of people gathered in a Budapest cemetery, with hundreds of secret policemen among them.)

This imposing anthology, which consisted of contributions by 76 authors in three thick volumes of more than 1,200 typewritten pages, was no doubt the first important venture with a significant influence in the history of the Hungarian samizdat movement. Furthermore, as an example of united political strivings on the part of all democratic opposition forces in Hungary, it also seemed to set a promising precedent, and it was perceived by the onetime communist party leaders as a real challenge. This is why they tried to prevent any further escalation of a resistance movement organized partly by the former ’56 tradition and partly according to the Polish patterns of self-organized Solidarity.

The ten-member editorial team included both ’56-ers and ’68-ers, “populists” and “urban” intellectuals, but the list of the 76 authors who contributed was even more diverse: old and young, prominent and hardly-known dissidents, writers, artists, scholars, etc. all readily contributed writings. The contributors included Gyula Illyés, György Petri, István Csurka, György Konrád, Sándor Bali, Sándor Weöres, Lajos Vargyas, and Piroska Szántó, just to name a few. Many of their memoirs, essays, and studies revolved around the relevant traditions of Hungarian national democratic movements and the chances of reviving these traditions. For all their differences, the authors equally shared sincere respect for István Bibó’s personality and his ideas. They also shared the belief that the only solution for the miseries of the Eastern Bloc countries, including Hungary, was real democratic changes in the principle of self-determination. In other words, both the sinister “heritages” of Stalinism and extreme right-wing nationalism should be rejected once and for all.

This kind of common consensus was a real revelation at the time, and in fact the main result of the collective venture of the book published in commemoration of Bibó was that it helped further a rediscovery of the real tradition of the independent, democratic spirit of Hungarian resistance movements, which had been suppressed and forgotten for a long time, together with the 1956 revolution. However, this was not the only positive effect of the book. It also helped break several taboos, making sensitive and long-suppressed issues, like the real heritage of 1956, the historical trauma of the Trianon Peace Treaty of 1920, and the Hungarian Holocaust in 1944 subjects in the public discourse again, along with the latent survival of anti-Semitism in the country and the forced assimilation of ethnic Hungarian minorities in the neighboring states.