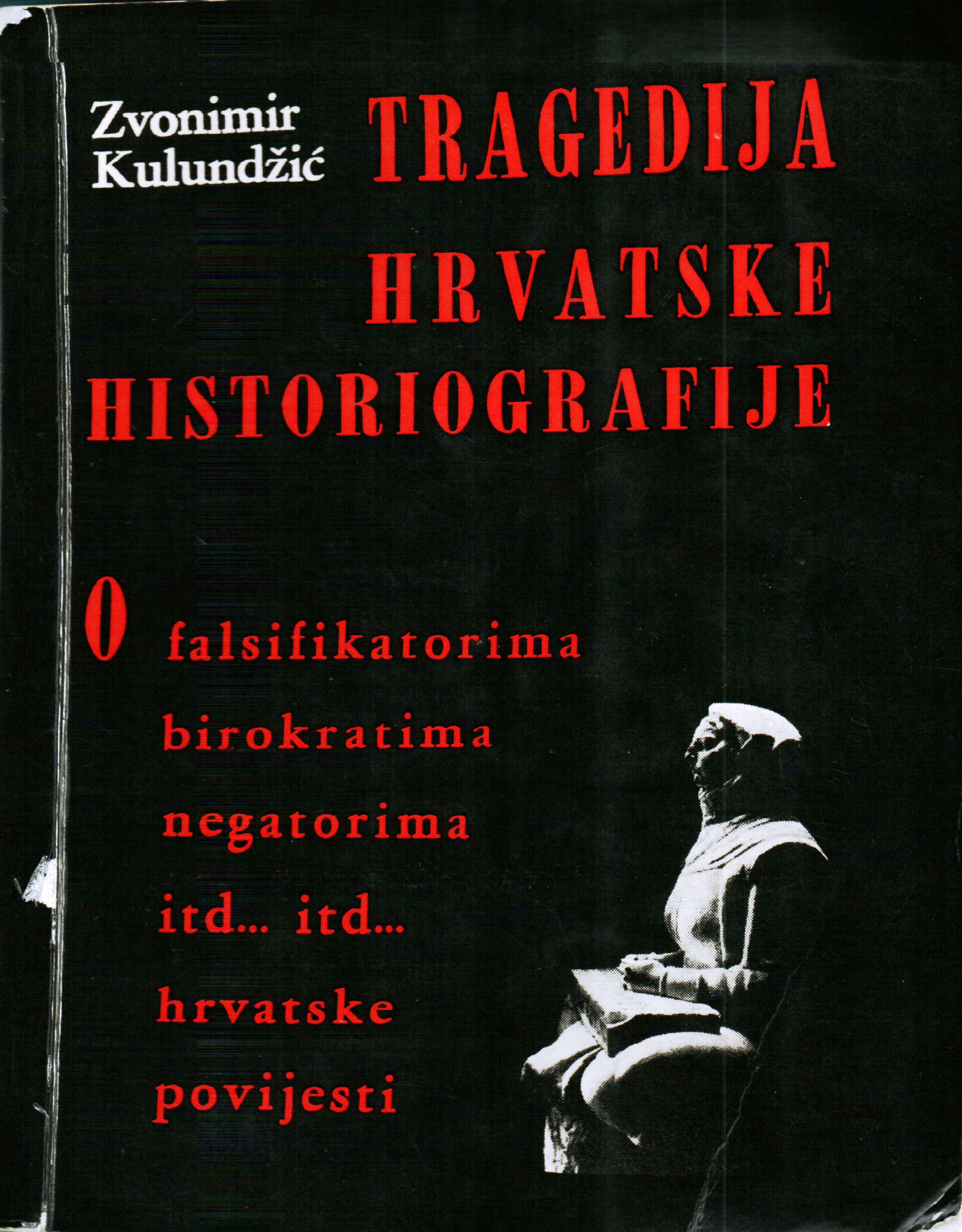

The book Tragedija hrvatske histoirografije (The Tragedy of Croatian Historiography) (Zagreb: self-published, 1970) provoked one of the most controversial debates in Croatian historiography. Kulundžić criticised institutional historiography which, in his opinion, functioned at the behest of the authorities. He thought that Croatian historians were methodologically conservative and that they avoided elaborating certain important themes from Croatian national history (such as the first printing press on Croatian soil, the date of establishment of the University of Zagreb, the Croatian identity of Dubrovnik), or even falsified it. He said that the tragedy of Croatian historiography is that "it was administered by those who served the former regimes subconsciously," having in mind historians who worked and published textbooks during the time of the Ustasha regime in the Independent State of Croatia, but also under socialism (p. 7). He argued that these intellectuals "due to their feelings of guilt, transposed their sins over the nation and thus developed what we call a sense of the entire nation’s guilt." He criticised academic historians in the most prestigious institutions (Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Science, Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb) as professionally self-satisfied, methodologically conservative, faulting them for failing to respect the criteria for the advancement of professors and scholarly, etc.

As a beginning for healing in cultural life, he called for "the introduction of the principle of responsibility for everyone's public work" and a critical approach toward “the forgers of national history” (p. 385). At the end of the book, he emphasised that "our official historiography believes that it is her duty to negate and minimize everything we have done and achieved over our long and bloody, but unusually glorious and honourable history. (...) This is one of the essential aspects of the tragedy of Croatian historiography - about which I want to initiate debate"(p. 407).

In defending the dignity of their profession and the status of university professors, the representatives of academic historians did not emphasise the quality of their works but criticised Kulundžić because he did not have a degree in history, and they labelled his writing as trivial. Academic historians saw in his publicist writing a dangerous rival in the struggle for social recognition and affirmation. Kulundžić was the most prominent representative of the non-academic historians, because his works quickly reached a broad audience. The first edition of the book immediately sold out (within a week), so he published another expanded edition in the same year. He quickly gained readers because he communicated directly with them - they were mostly subscribers to his self-published editions, and he encouraged them to communicate with him by inviting them to send their remarks, assessments and suggestions.

Renata Jambrešić Kirin (2003, p. 18) asserts that Kulundžić was characterised by ideological inconsistency, scandalous tendentiousness, destructive social criticism and the ability to provoke the lethargic cultural and scholarly public. She believes that Kulundžić's critique of academic institutions was motivated by the disavowal of his hypothesis on Kosinj as the site of the first Croatian printer, and was partly under the influence of the wider intellectual revolt in Croatia in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Although indelicate, this book opened certain taboo topics such as the question of the relationship between academics and the political authorities by articulating the assumption of loyalty and conformism by members of the academic community. The book is one of the best examples of dissent against the dominant historiographic practices.