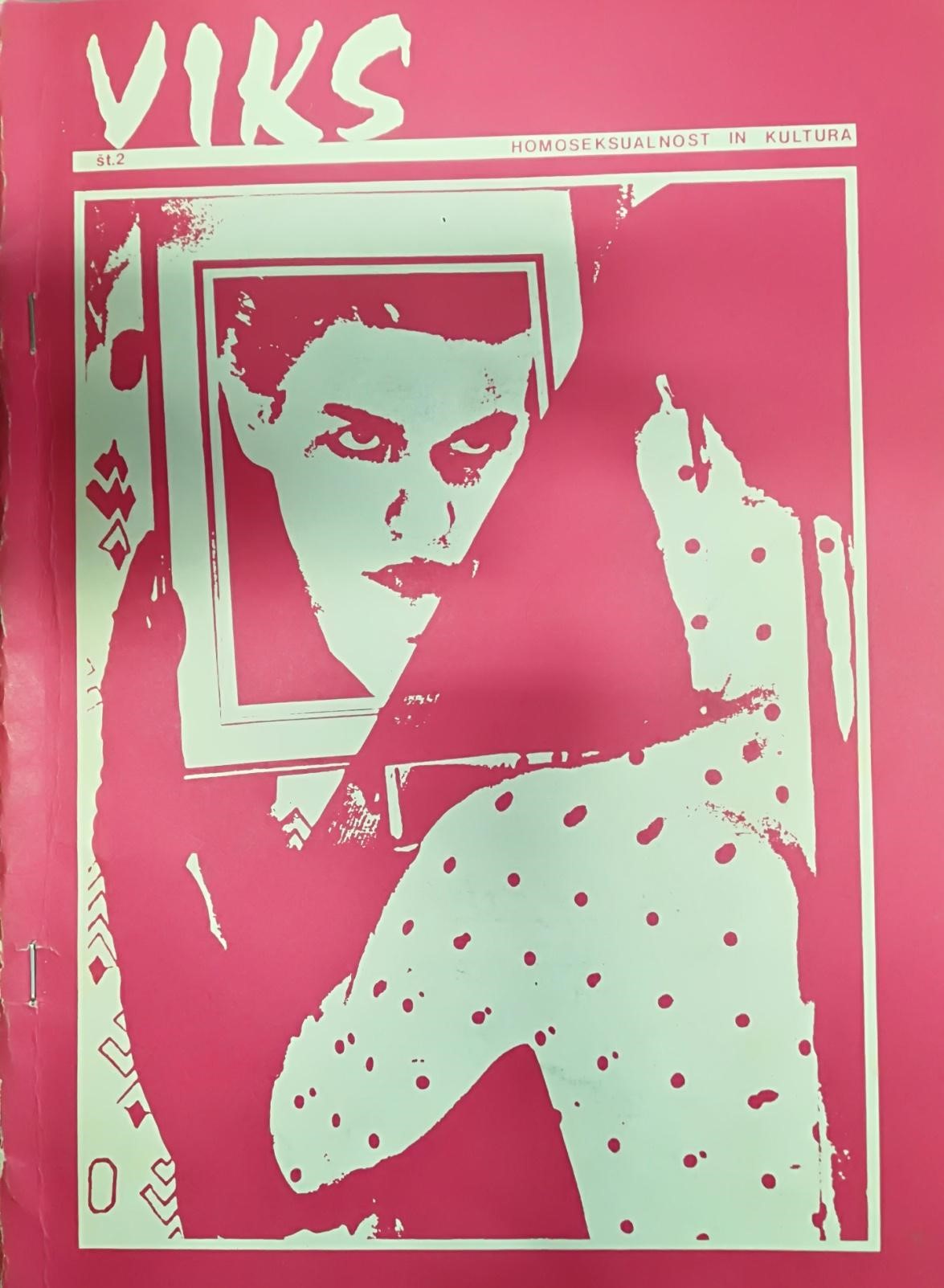

The second issue of the magazine Viks, entitled “Homosexuality and Culture,” came out on April 24, 1984, the opening day of the Magnus Film Festival, the first cultural manifestation dedicated to homosexuality in any socialist country. The magazine was edited by a group of gays and lesbians who gathered around the youth cultural center ŠKUC and organized the festival. This special edition of the magazine was printed in 600 copies and handed to audiences at the festival. It contains 42 pages, and approximately 20 illustrations with contemporary, easily recognizable European gay subcultural motifs. Over the three following decades, this issue of Viks gained a cult status in Slovenian and the post-Yugoslav LGBT community, and was exhibited at events dedicated to the history of homosexuality and the LGBT movement.

Alongside the festival’s program and a schedule of affiliated cultural and club events, in an effort to appeal to the younger generation of Ljubljana’s gays, lesbians and artists, Viks also carried several lengthy programmatic articles and interviews with emancipatory, educational and mobilizing overtones. Thus it aligned itself politically and theoretically with contemporary liberationist, leftist and counter-cultural movements in Slovenia and Western Europe. These texts promote an ideal of freely and openly lived (homo)sexuality. Non-normative sexual practices were viewed as strongly dissident in nature, but not so much against socialism as against patriarchal and traditional forms of sexual and family life.

The article “Pink Love under the Red Stars – Homosexuality under Real Socialism” (“Roza ljubezen pod rdečimi zvezdami – homoseksualizem pod realnim socializmom,” pp. 18-21) delivers a historical overview of the legal and social status of same-sex sexual and emotional relationships in socialist countries. The anonymous author is equally critical of the 20th century discrimination of homosexuality both in western liberal democracies and socialist countries. However, the Stalinist period in the USSR was seen as especially brutal and arduous insofar as it attributed negative political meanings to homosexuality, declaring homosexuals “traitors,” foreign “spies,” decadent bourgeoisie, and enemies of socialism. Soviet homosexuals, the article suggests, were not able to recover from this traumatic period, and were still unable to engage with emancipatory social movements and practices. At the same time, the example of the German Democratic Republic (GDR, known also as East Germany) is held as an example of both positive changes in communist stance on homosexuality, and a way in which, since the late 1970s, a dialogue could take place between the government and gay and lesbian groups.