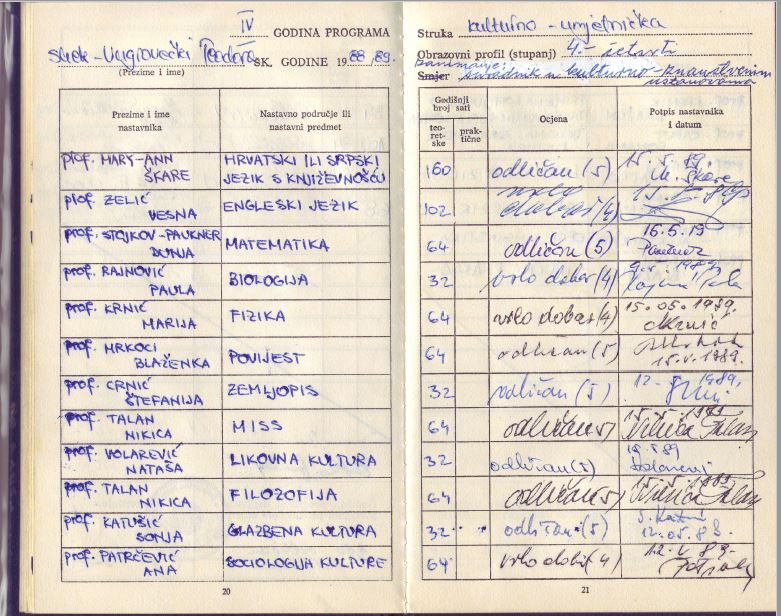

The owner of the collection, Vlatka Horvat (née Penzar, 1971-), preserved photographs and the class samizdat from the period when she attended the Educational Centre for Languages in Zagreb (1985-89), albeit not with some special intention but rather simply as memorabilia from her secondary school days. Vlatka was on the editorial board of the samizdat and participated in its design. Her older brother, Neven, also a former student in the school and the author of original artworks based on the Asterix cartoon, was also involved. The idea of describing this collection occurred to Teodora Shek Brnardić, HIP’s national task manager and Vlatka’s classmate, who attended the same elementary and secondary school with classics programme.

Former classics students who attended this secondary school in Zagreb during the late socialist era were aware that they had avoided the so-called "Šuvar reform" of the school system (also known as the “Šuvarica”), which began in the Socialist Republic of Croatia in 1975/76. The reform was named after Stipe Šuvar (Ph.D.), who was then one of the leading communists in both Croatia and Yugoslavia as a whole. Since the fall of 1974, he had been in the republic’s Education and Culture Secretary (equivalent to the present-day minister). After the crises of 1968 and 1971, the ensuing purges and the adoption of the 1974 Constitution, the League of Communists decided that a comprehensive education reform should be one of the responses to the previous situation in order to create a uniform secondary school system. It was supposed to abolish the existing dualism of general secondary schools that prepared students for university study and vocational schools that mainly prepared them for the labour market (Munjiza 2009, 86).

In the communist world-view, such a dualistic system created class inequality, and it had to be eradicated by the introduction of so-called “directed education.” From Šuvar's Marxist perspective, one of the functions of such education was to erase the difference between “those who think” and “those who work.” The members of the working class had to be given an opportunity to engage in intellectual professions and activities, and “intellectuals” had to become acquainted with the basics of labour in the course of production (Baćević 2006,117). In the framework of the 1977 reforms, all existing secondary schools and gymnasia were abolished and replaced by so-called centres for directed education. Their curricula and educational plan in the first two years bore the same name “common general basics.” There students had to acquire indistinguishable, sufficient knowledge to continue their education at the university level, whereas differentiation according to professions (approximately 300) would appear in the third and fourth class (Munjiza 2009, 89).

By promoting the concept of “school and factory,” Šuvar nominally sought to eradicate unemployment because, in his view, the economic needs of labour organisations (the term for companies in Yugoslav socialism) had to dictate the creation of certain professions, and from there, if necessary, the workers would continue their education at the university level. The slogan of Šuvar’s reforms followed this dictate: “get a job as soon as possible and let the labour organisations select those who will be further educated” (Šuvar 1977, 229).

The Belgrade sociologist Jana Baćević thoughtfully observed that the economic reasons for implementing reforms may have been only incidental. The desire to wipe out class inequality actually meant criticism of the apparently privileged class, whose members were bureaucrats, scientists and intellectuals, that is, more or less all university-educated people. Baćević argued that directed education was meant to “break apart the reproduction of a group of critically-oriented intellectuals, mostly of civic origin, who possessed the language, means and ways to formulate a comprehensive critique of contemporary socialist society, which on two occasions – in 1968 and 1971 - was perceived as a direct threat to the system as a whole.” Direct education was in a way meant to prevent possible future social upheavals, as intellectuals in the late 1960s proved to be the main critics of socialist society (Baćević 2006, 117 i 120). The reformers particularly targeted the gymnasia and their humanist education, which, according to Šuvar, was elitist because it generated people who worked “outside of material production” and who lived “exceptionally” and “in an elite manner.” (Šuvar 1977, 6): “I would like to mention the example of gymnasia. Now our attempts at a deeper transformation of the gymnasia have been met with almost spontaneous resistance by the wider and insufficiently informed public. One third of gymnasium students in Croatia are not going to university and cannot find a job and nobody cares about it. Rather, everybody is yelling at us for daring to touch upon the gymnasium as allegedly the only school that is worthwhile” (Šuvar 1977, 227).

Public classical gymnasia, of which there were only two, namely, one in Zagreb and one in Split, first came under fire and were declared "relics of the past and the most old-fashioned schools" (Pasini 1975, 60). Both of them were abolished and attached to other centres of directed education (the one in Zagreb was attached to the Educational Centre for Languages and the one in Split to the Education Centre for Construction). Understandably, resistance to abolishing the gymnasia was great because it had somehow made the school curriculum less intellectual, and its implementation was slipshod. Philologist Dragutin Rosandić testified to this fact: “The reform model during Šuvar’s term was bad because it reduced the humanist education at the expense of the vocational education, which made the school less intellectual and subordinated it to the needs of production. His idea was to abolish the differences between the intellectual and the manual, the school and the factory, and in this endeavour he encountered great resistance. Although a sociologist, Šuvar advocated a concept that set the humanistic role of education in the background and reduced everything to the school and factory, which was the current slogan. That is why the decision to equate gymnasia and vocational schools was met with great resistance in the humanist circles” (Lilek 2018).

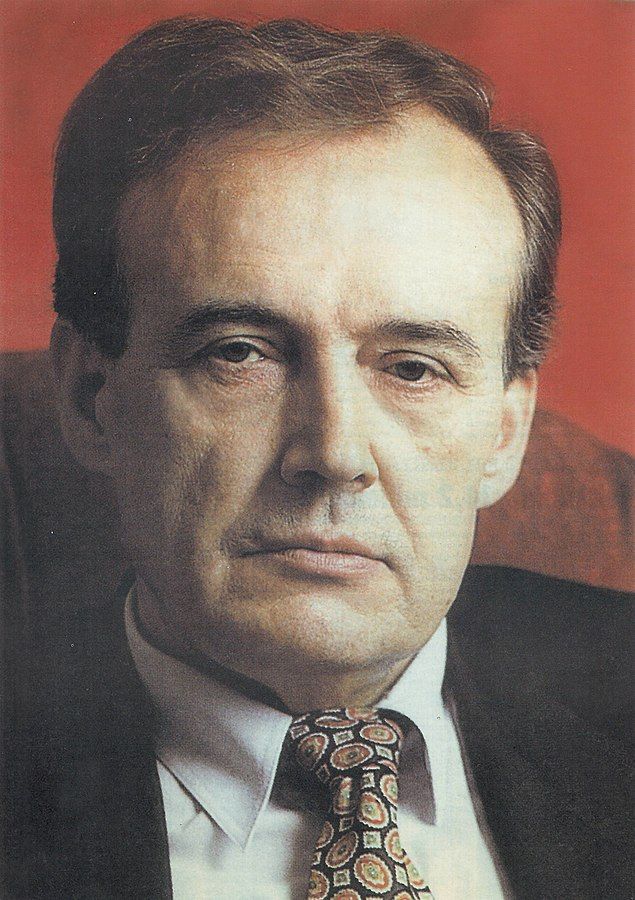

Nevertheless, the classics program, that is, the teaching of the Latin and Greek languages along with philosophy, managed to survive at the Zagreb Educational Centre for Languages, mostly thanks to the resistance of the former headmaster, Prof. Marijan Bručić: “When the campaign against the classical gymnasium as an elitist bourgeois entity was launched, Prof. [Marijan] Bručić, with the wholehearted support of Prof. [Vladimir] Vratović, began to fight like a lion against the well-known Stipe Šuvar (...) and managed to retain our Latin and Greek language programmes. We were, however, being placed in all kinds of pedagogical and language centres, but thanks mostly to Prof. Bručić, we would stay in their framework at least as a ‘classical shift’ headed by Bručić himself” (Lopina 2007, 435).

Generally speaking, Šuvar’s reform showed serious shortcomings already in the mid-1980s. The reason was not only the already-mentioned poor implementation, but also the economic crisis that set in after Josip Broz Tito’s death in 1980. The economic sector simply failed to adapt to the concept of directed education (Baćević 2006, 120).