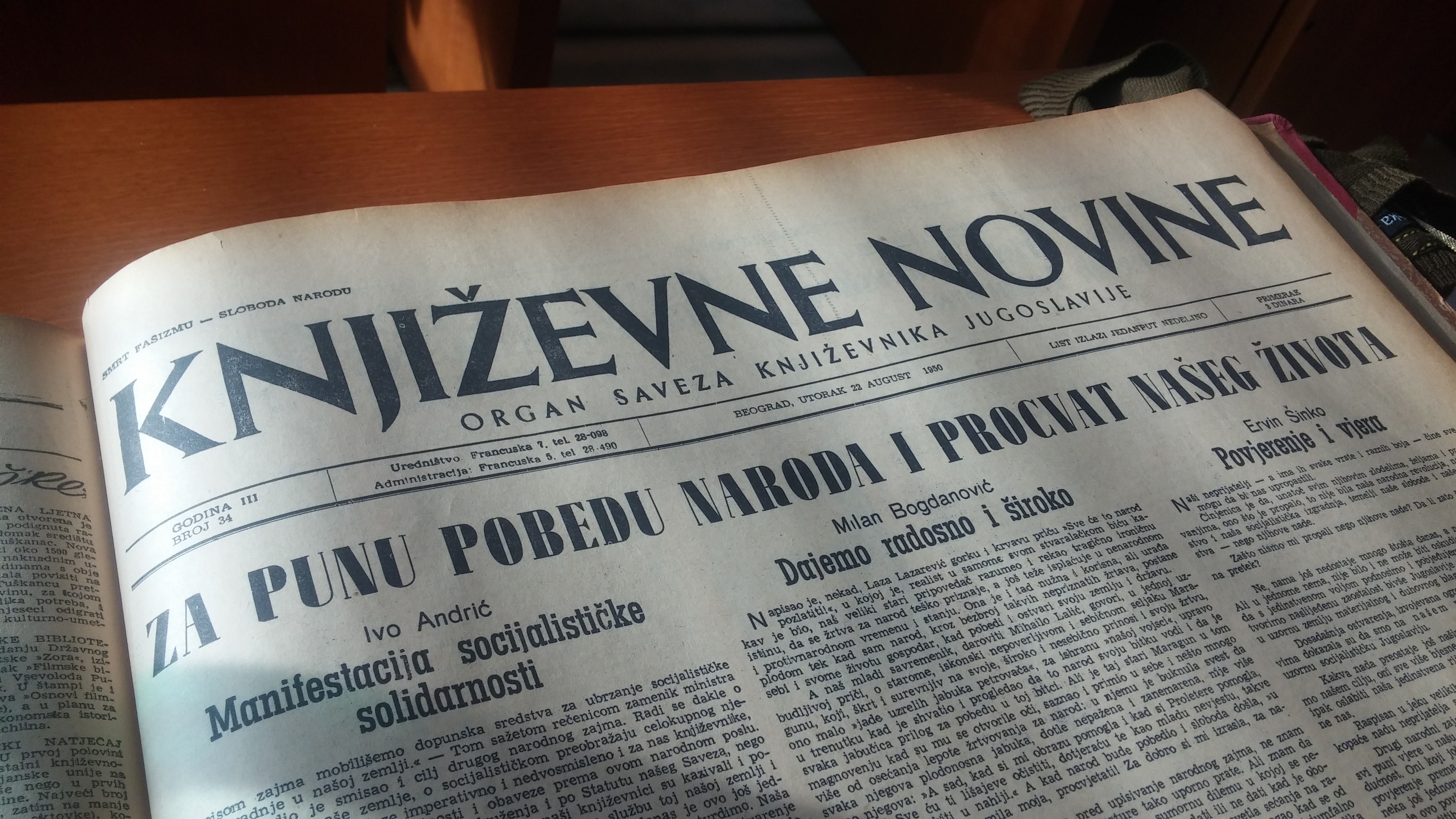

‘Književne novine’ [Literary News] began to appear soon after the end of the Second World War, more precisely, in 1948. In the course of the 1950s, it established itself as one of the most influential literary journals in Yugoslavia. In this period, the paper was headed by Tanasije Mladenović, the longest-serving editor at ‘Književne novine’ (see more under person researched). In the beginning, the paper was the official journal of the Yugoslav Writers’ Union, subsequently to grow into the official journal of the Association of Writers of Serbia. Nevertheless, the paper retained its Yugoslav character and continued to publish literary articles from other republics. The journal was often the object of criticism and was banned numerous times. In addition, the entire editorial staff was replaced several times, which limited freedom of expression at least temporarily.

According to the description of the journal published on the website of the Association of Writers of Serbia, ‘The paper was not unaffected by ideology but it inevitably played a role in the achievement of artistic freedom and the democratization of society. Its role is, nonetheless, a literary one; it is a testimony to literary and to cultural life, their trends, processes and transformations’.

The journal was confronted with its first ban as early as 1949, after it published the satirical text ‘Krilov i Ezop’ [Krylov and Aesop] by Moša Pijade, only to be blasted again the following year for printing ‘Jeretičke priče’ [Heretical Tales] by Branko Ćopić (more on this under featured item). This is one of the most often mentioned examples of censorship in the former Yugoslavia. ‘Književne novine’ was temporarily silenced in 1952 and was not to reappear until January 1954. Thus ended the first wave of conflict with the authorities.

However, the dispute that occurred in the second half of the 1960s was much more signficant. The pressure on ‘Književne novine’ was precisely, ‘one of the most illustrative examples of the influence of the authorities on culture and [artistic] creation from the era of early communist practice until liberalization, especially because ‘Književne novine’ was a kind of litmus test of the general climate in cultural and social life, as well as in the League of Communists’ (R. Vučetić, 2016, p. 170).

The attack on ‘Književne novine’ came after it carried a debate on the 1967 ‘Proposal for Consideration’. The Proposal was the response of 40 Serbian intellectuals, members of the Association of Writers of Serbia, to the Croatian ‘Declaration Concerning the Name and Position of the Croatian Literary Language’ signed by 140 Croatian intellectuals (J. Dragović-Soso, 2004, p. 60). The Croatian Declaration on language triggered a controversy over the attributes of national identity within Yugoslavia and expressed dissatisfaction with, as was stated, the imposition of Serbian as the state language. The Association of Writers of Serbia reacted by accepting the proposal to separate the two languages, even calling on the Federal Parliament to amend the Constitution to remove the language names ‘Serbo-Croatian’ and ‘Croato-Serbian’. The party’s reaction to this polemic was to expell a number of the signatories from the party, while others were dismissed from their jobs. ‘Književne novine’ was among the targets at that time, along with its chief editor, the poet Tanasije Mladenović (J. Dragović-Soso, 2004, p. 65). The publication of the debate and public expression of standpoints led to sharp accusations on the part of the party. ‘Most often, almost uninterruptedly, “Književne novine” was accused of writing about national relations within Yugoslavia and about the socio-political system’ (R. Vučetić, 2016, p. 172). Several months of tension and allegations of nationalism ended with Mladenović being expelled from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and replaced as chief editor of ‘Književne novine’.

Even in the wake of this pressure, the paper continued its independent editorial policy, thus allowing students to give public expression to their views in June 1968 during the student protests. In the following year, a court order prohibited ‘Književne novine’ for printing the text ‘Five Variations on the Theme of the Hot Prague Spring ’68’ (issue of 30 August 1969) by Zoran Gluščević, the editor at that time who received a prison sentence for this text. The sentence was subsequently rescinded. ‘Književne novine’, however, was temporarily banned at this time and was not to reappear until April 1970 (R. Vučetić, 2016, p. 187). Further bans were imposed in the following years – at least two court orders withdrawing the paper are recorded for 1971 and 1974.

The paper was again shut down temporarily in 1983 after the majority of collaborators, prompted by a party directive, submitted their resignation (S. Cvetković, K. Nikolić, Đ. Tripković, 2010, p. 262–273).

Two more issues were banned by court order in the late 1980s. The first was imposed in 1986 for the publishing of the poem ‘Naša pesma’ (Our Poem) by Predrag Čudić (nr. 703/1986), and the second in 1988 (nr. 757–58/1988) for printing the text ‘Zločinci i žrtve’ (Perpetrators and Victims) by Dragoslav Mihailović, which dealt with the political prison Goli Otok.

‘Književne novine’ is still in print today.