This ad-hoc collection includes the archival documents relating to the 1977 movement for human rights in Romania, which are currently preserved in several different collections of CNSAS, such as the Penal Fonds, the Informative Fonds and the Manuscript Collection. The rationale behind defining this ad-hoc collection is to offer a research guide for those interested in better understanding this ephemeral but large collective protest, the intellectual profiles of its main defenders and the reactions of the Securitate against it. Thus, it does not include all the files in the CNSAS Archives of the over 200 individuals who endorsed this movement, but only the files of those individuals who defied the communist regime in more ways than this one. More precisely, this ad-hoc collection includes the files of the writer Paul Goma, the main proponent of this movement, and of three other persons who distinguished themselves not only by signing the collective letter of protest, but also by formulating their own criticism of the human rights violations of the Ceaușescu regime: the psychiatrist Ion Vianu, the writer Ion Negoițescu and the worker Vasile Paraschiv, victim of psychiatric abuses. The importance of this ad-hoc collection resides in the fact that it illustrates how the secret police collected information about individuals in general, and about writers in particular. On the one hand, the Goma Movement Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS shows that the Securitate managed to attract many individuals from the community of Romanian writers to become its “sources” of information. On the other hand, the collection shows how the secret police managed to construct data bases containing complex information about very diverse individuals suspected of potentially “hostile actions” against the communist regime.

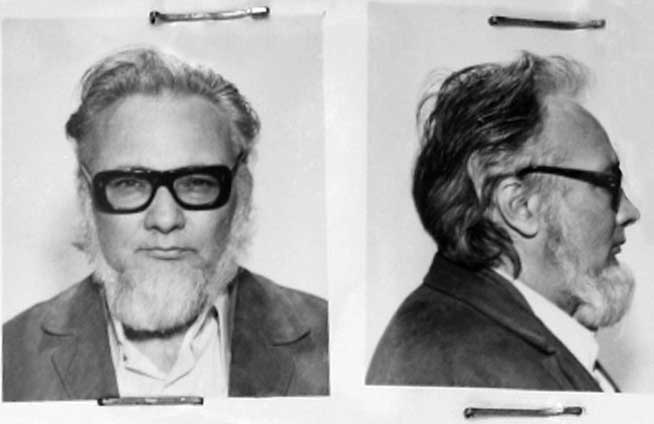

The informative surveillance of Paul Goma is important and unique because he had one of the longest careers as an opponent of the Romanian communist regime. There were three occasions when Goma opted for defiance instead of compliance: (1) when he joined the student unrest of 1956; (2) when he decided to publish a novel abroad without approval from the Party; and (3) when he tried to establish a human rights movement in 1977. The CNSAS Archives reflects all these moments in Goma’s dissident career. The first acts of defiance occurred in November 1956, a few days after the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution. At the time, Goma was a student at the University of Bucharest and during a seminar he read a “hostile” excerpt from one of his novels. In fact, the paragraph referred to the negative effects of collectivisation. Like many other Romanian students who supported the Hungarian Revolution, Goma was arrested on 22 November 1956, and few months later, in March 1957, he was sentenced to two years in prison for “public agitation.” He was released from prison in 1958, but the coercion continued by imposing on him forced domicile in a village in the Bărăgan Plain, which ended only in 1963. The Penal File made by the Securitate officers on Goma dates to those years. It contains only a few documents, the most important of which is sentence no. 487 of the Bucharest Military Tribunal, dated 20 March 1957 (ACNSAS, Penal Fonds, File FP 47310, f. 14).

After his release, Paul Goma continued his fight against the communist regime. From the period following his release from forced domicile in 1963, there is interesting but mostly overlooked evidence. As in the case of many former political prisoners, Goma was approached in 1967 by the secret police with a proposal of collaboration (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/ 3, f. 31). Unlike others, it results that from a note of 17 November 1969 that he had refused to be “attracted into collaboration” (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/ 3, f. 72-73). This refusal is worth mentioning in order to highlight the fact that the option of refusing such offers from Securitate meant neither a return to prison nor any immediate repression. It did, however, mean perpetual marginalisation. Paradoxically enough, this episode was almost simultaneous with Goma’s enrolment in the Communist Party, which occurred during the enthusiasm of August 1968, when Ceaușescu made political capital by by publicly condemning the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Treaty Organisation troops.

The informative surveillance of Paul Goma is reflected in twenty-one volumes compiled by the secret police. Their surveillance of him opened in 1971 and the main reason was his attempt to publish abroad a novel called Ostinato. Goma’s file illustrates that the secret police had been informed about his plans by various “sources,” so it intercepted his letters and listened his telephone calls. The CNSAS Archives also illustrate the fact that the Securitate studied the motivation for the rejection of Ostinato from publication, which came from one of the most important publishers in Romania, Cartea Românească. The novel Ostinato focused on the theme of liberty, which the author presented as an idea that consumed a group of prisoners who tackled it obsessively during their term in jail until they ended up as the “prisoners” of this idea. In spite of being under surveillance, Goma managed to translate his books into German with the help of an Austrian doctoral student specialising in Romanian studies, who succeeded in taking the manuscript across the border and finding a publisher. Suhrkamp published Ostinato in 1971 and launched the volume at the Frankfurt International Book Fair as a book censored by the Romanian communist regime. Goma’s book thus registered a tremendous and rather unexpected success, so a year later Suhrkamp published another volume, Uşa noastră cea de toate zilele (Our everyday door), also rejected by censorship because one of the main characters dangerously resembled Elena Ceauşescu. Goma’s performance was rather unique in communist Romania, as few authors dared to publish abroad without official approval. Obviously, the publication of these novels annoyed the Romanian communist authorities greatly, while stirring turmoil among fellow writers and apparatchiks in the field of culture. This event occurred in the context of the so-called Theses of July 1971, which reinforced ideological control over culture and instituted increasing restrictions on the circulation of people and information across the borders of Romania in order to curtail Western influence upon Romanian authors. The secret police suffered a great failure with the publication of Ostinato, so from then on, between 1971 and 1977, Goma’s file contains an enormous number of notes about intercepted telephone conversations and informative notes on him and the persons who supported him. This is the main particularity of Paul Goma’s file. He was more than a target for the Securitate. His case was used in order to make a database about the cultural world of Romania. Thus, the file is full of biographical profiles of the persons who were connected with Goma in a way or another.

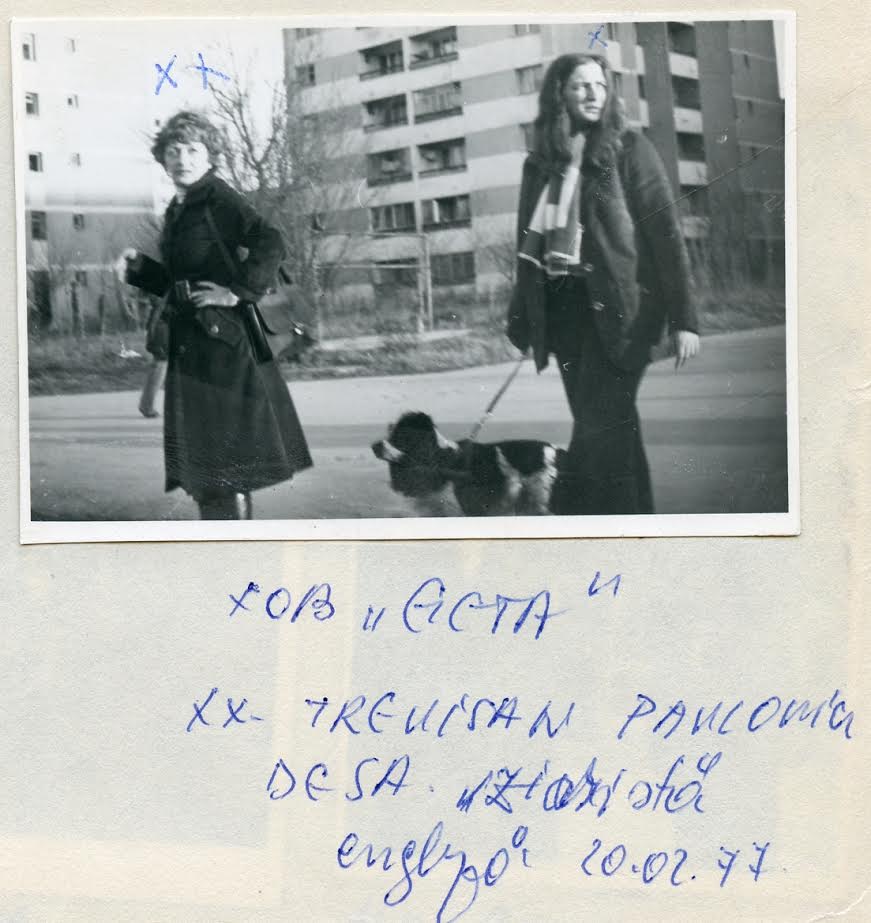

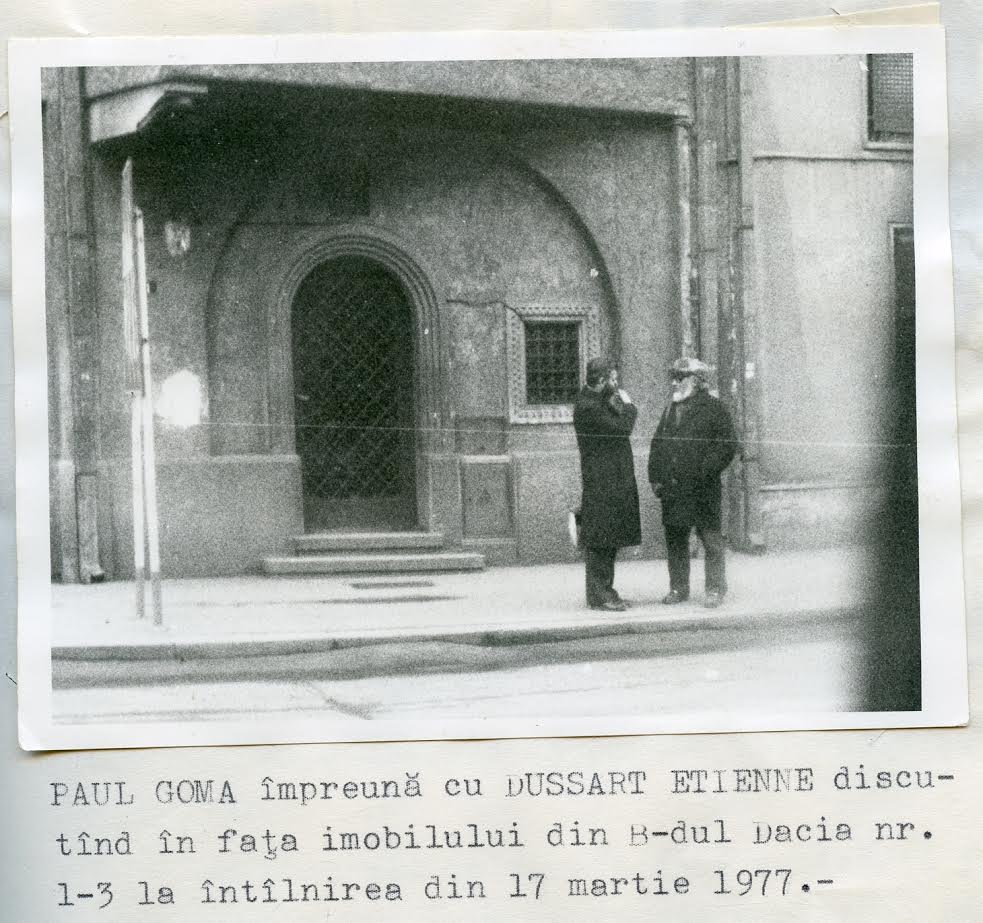

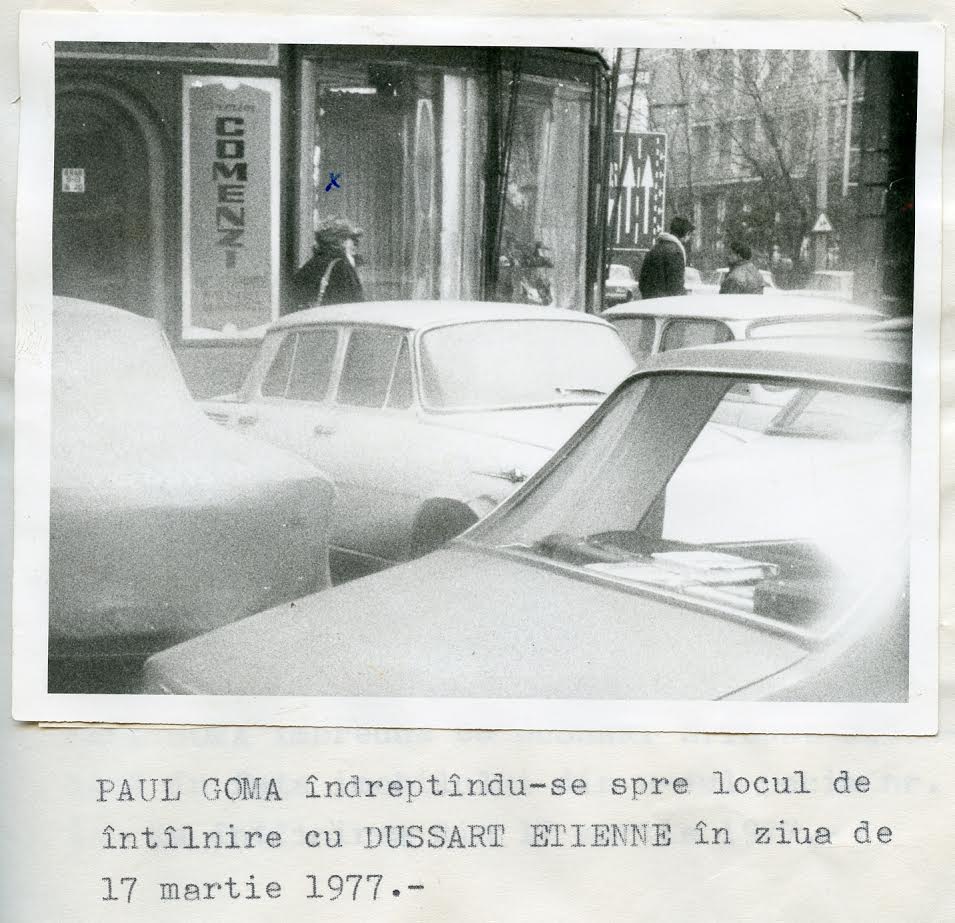

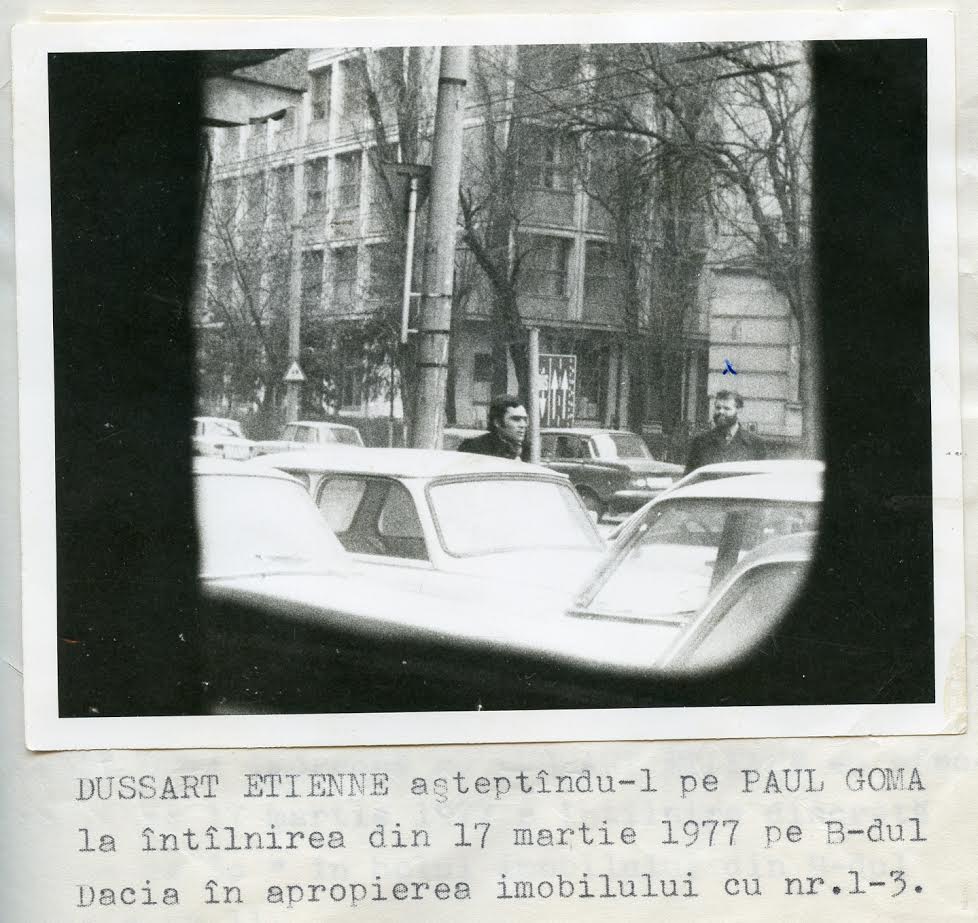

The last stage in Goma’s file reflects his involvement in establishing a movement for human rights in Romania, following the model of Charter 77. In January 1977, Paul Goma wrote a letter to the Czech playwright Pavel Kohout, one of the signatories of Charter 77, in order to express his solidarity with their protest against the violation of human rights. After Radio Free Europe broadcast this letter on 9 February 1977, over several weeks about 200 people signed collective letter of protest against the violation of human rights which were guaranteed by the Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Romania. This letter was to be sent to the CSCE (Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe) Follow-Up meeting, which was to be held in Belgrade in 1977. Faced with a growing problem, the Securitate took resolute action to curtail the spread of the movement. The entire Goma family was immediately put under permanent surveillance. This is reflected in an enormous amount of stakeout reports, intercepted calls, correspondence reports, surveillance photographs and informative notes about the persons who contacted Goma at his residence, including Ion Negoițescu, Ion Vianu and Vasile Paraschiv. These individuals were closely monitored even after Goma was arrested on 1 April 1977. From among the different types of documents in this collection, worthy of special mention is the series of photographs of February–March 1977, picturing Goma and his wife meeting foreign diplomats and journalists, which shows the Romanian secret police as wardens of transnational encounters. They are part of the documentation prepared by the Securitate to build a case about Paul Goma’s anti-regime activities and justify his arrest. The photographs illustrate that the process of keeping a dissident under surveillance in communist Romania included not only the targeted person, but also all his family members. It is noteworthy that the surveillance focused primarily on encounters with foreign diplomats and journalists, who were able to transmit across the borders the critical messages about the abuses of Ceaușescu’s regime and, in absence of alternative internal sources of information, make them known to all Romanians via Western broadcasting agencies. Thus, after their first meeting with a dissident, foreign nationals turned automatically into targets of the Securitate. One photograph, which seems to have been taken from the car from where the secret police officers conducted their surveillance, illustrates that the target was not Goma, but the foreign diplomat who was waiting for him.

Alongside these surveillance photographs, this collection covering the surveillance of Goma fully illustrates the actions designed by the Securitate in order to limit his influence, which are included in their so-called “plans of action.” Drafted immediately after the broadcast of Goma’s letters by Radio Free Europe, a plan of measures dated 11 February 1977 includes the following actions: to “positively influence” (i.e. persuade to retract) Goma and the others around him, beginning with his wife; to bring Goma into disrepute among other former political prisoners and fellow writers (in order to curtail the spread of this collective protest), to interrupt his channels of cross-border communication, i.e. phone calls, contacts with journalists or diplomats, with a special mention of the Belgian diplomat Etiènne Dussart, who had actually sent the letters abroad (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/4, f. 312–315). Researchers of the secret police files know that for each monitored individual the agents in charge drafted and periodically updated plans of action, which usually required the approval of the higher-ranking Securitate officer who supervised the surveillance of the respective person. Remarkable in Goma’s case is the endorsement of such a plan of action by the highest possible office holders in the Ministry of the Interior, to which the Direction of State Security was subordinated in 1977. The plan of action of 17 March 1977, which is a masterpiece of this collection, illustrates an intermediate stage of harassment before his arrest on 1 April. Remarkable about it is the endorsement at the highest possible level: it was countersigned by Nicolae Pleșiță, then first deputy minister, and finally approved by Teodor Coman, the minister of the interior. The hierarchical level of those who endorsed this plan testifies to the great importance attached to this case. Entitled “Plan of action for continuing the actions for annihilating and neutralising the hostile activities which Paul Goma initiated being, instigated and supported by Radio Free Europe and other reactionary centres in the West,” it includes four separate types of action. The first type consists of the so-called “actions of discouragement, disorientation and intimidation,” which were directed mainly against Goma, though the necessity of tackling his supporters separately is also mentioned. This type of action consists mostly of various forms of harassment up to the level of deporting him outside Bucharest in order to seclude him from his channels of communication across the border. These actions of rather soft repression were to be accompanied by attempts to bring this problematic episode to a faster and neater end by convincing Goma to either give up or emigrate. The second category of actions included the use of foreign press and publications in the attempt to compromise Goma and implicitly the movement for human rights initiated by him among the Romanian emigration and Western audiences. The third category referred to actions of counterbalancing the denigrating messages broadcast by Radio Free Europe, which was the broadcasting agency that helped Goma the most. Finally, the fourth category consisted in actions to compromise Goma among the personnel of the Western embassies in Bucharest, with the aim of depriving him of his channels of communication with Radio Free Europe or other members of the exile community (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/6, f. 109-112).

In spite of these measures, Goma managed until his arrest of 1 April 1977 to collect about 200 signatures on the common letter of protest against human rights abuses in Romania, which represented about as significant an endorsement as Charter 77 attracted the same year. The document listing all these persons is part of this collection (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, 61–78), and copies of the document are to be found in the Paul Goma Private Collection in Paris and in the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives in Budapest (OSA/RFE Archives, Romanian Fond, 300/60/5/Box 6, File Dissidents: Paul Goma). It is interesting to note that Goma’s file of informative surveillance abounds in statistics regarding the signatories of the letter to the CSCE Follow-up Meeting in Belgrade, which start with the identification of the addresses of those involved, continue with basic personal data and driving motivations, and end with the measures applied to each and every person involved. These statistics were constantly updated, but the data appear slightly contradictory. However, the numbers registered in the Radio Free Europe files (due to Goma’s careful transmission of names through various channels of communication) and those in the Securitate files (which included also the lists confiscated on the day of Goma’s arrest) largely converge. The collection of data about all those involved in the Goma Movement was crucial for the mission of the Securitate of nipping the movement in the bud. Accordingly, a note of the Ministry of the Interior specifies the specific data that officers sent to each county to “grasp the situation” must have collected in order to devise on their basis the “neutralisation measures,” as follows: current political attitude, former criminal record and political background, professional background, moral and social profile, family background (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, f. 57–58). From the statistics compiled by the secret police it seems that 192 people declared their full support for the letter against human rights abuses – directly, by post or by phone – until Goma’s arrest on 1 April 1977 (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, 205; File I 2217/12, 169-176). These were the actual signatories of the collective letter of protest, still more tried to join even after Goma went to prison. The statistical data compiled by the secret police indicate a total number of around 430 persons who either adhered to the letter or just tried to contact Goma (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, 81–83).

A particular document from the Archives of CNSAS practically epitomises the typical and efficient method which the Securitate employed in the case of the Goma Movement and subsequently used against all those who attempted to establish networks of dissent in Romania: the transformation of an aggregate action against the communist regime into a multitude of individual motivations for expressing discontent with the regime. It is a coloured chart entitled “Chart of Paul Goma’s personal connections” (Schema legăturilor lui Paul Goma) and it is dated 1 April 1977, the day when the secret police arrested Goma (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, f. 89). The chart represents the summary of a thoroughly compiled data base and, in appearance it resembles the drawings made by teachers to facilitate the better understanding of a topic by their pupils. The chart was devised for the Securitate officers who were faced with an unprecedented challenge. At the same time, the chart represents an unusual type of document in the archives of the Securitate and thus it is worth looking closely at it. Although it does not represent the final stage in gathering information but only an intermediary analysis in support of the decision-making process, it is very telling for the promptitude of the secret police action in face of an extraordinary challenge and for its capacity of collecting complex data. The statistics compiled then constitutes today the main source for analysing the profile of the persons who endorsed the collective protest. More precisely, the chart contains a schematic representation of Paul Goma’s relations with other persons. The central field, which features Paul Goma, is connected left and right with two columns of differently coloured fields. The left-hand column seems to represent a typology of individuals whom Goma had contacted in order to send documents related to the activity of the emerging movement across the border to a Western country. They are divided into four categories: diplomats, foreign journalists, “reactionary elements from the emigration” and “autochthonous elements.” For the first three categories, there is data about the number and the country of origin, while the fourth seems to have been sub-divided according to the alleged motivation which the Securitate analysis highlighted as explanation for their support for Goma. In this respect, there are only two options: either a past extreme right background or a present desire to emigrate.

The right-hand column seems to categorise all those who had contacted Goma with the purpose of endorsing the movement. At the time when this chart was drawn up, the Securitate must have been able to scrutinise only 288 persons out of 430; this figure is added in pencil as a total. About these persons, there are three types of information offered: the actions taken (against them), their method of contacting Goma, and their political background (antecedente politice). Only regarding the methods of contacting Goma was the Securitate able to provide complete information about all 288 persons, of whom 138 had interacted directly with him, 109 by phone, 14 by post, 10 through intermediaries and 17 probably never, because they are in the category “intercepted by our organisation” (interceptați de organele noastre). Among the actions taken in order to dissuade these persons from supporting Goma, 12 received mandatory employment according to Law no. 25/1976 (which outlawed unemployment as “parasitism”), 12 were publicly criticised by their work colleagues, 47 received a warning, 11 were “positively influenced,” while 14 were Party members whose cases were to be handled by their local Party organisations. Finally, the information on the so-called political background seems to fit the categories of “enemies of the state” as defined by the Securitate. These were as follows: 8 former members of the extreme-right interwar Legionary movement (legionari), 19 previously convicted (in fact, former political prisoners), 92 dissatisfied at not receiving passports (for emigration, probably), 35 unemployed and 21 mentally ill (in fact, persons who suffered from psychiatric abuses).

The chart is accompanied by a table, which includes information about 192 individuals, named elemente apărute (elements [who have] appeared). This appellative in Securitate parlance suggests that this category included only those individuals who had actually endorsed the open letter of protest against the violation of human rights in Romania, which was addressed to the CSCE Follow-Up Conference in Belgrade and represented the most important document of this movement. About these individuals, the Securitate compiled a database with the following categories: criminal record, political background (i.e., party membership before communism), membership of the Romanian Communist Party or Romanian Communist Youth Organisation, employment status (i.e., jobless, retired, etc.). Of these individuals, 37 were still under verification at the date when the table must have been prepared for an internal Securitate analysis (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, f. 81). There are two appendixes to this table. The first includes data about 430 persoane care au avut tangență cu Bărbosul (persons who have had passing contact with “the Bearded man” [ Goma’s codename in the Securitate files]). This category contains more individuals because it seems to cover all those who contacted Goma, including those who did not immediately sign the open letter. It is worth noting that this category is defined using “normal” words in the Romanian language, unlike the previous one which was in communist newspeak. About the persons who contacted Goma, however, the Securitate collected more comprehensive data than about the signatories. These data include the following categories: age, nationality (i.e., ethnic origin), profession, education, previous record in the database of the Ministry of the Interior (i.e., previous acts of defying the communist regime), criminal record, and “other motives,” which included three sub-categories: former members of the extreme right Legionary movement, former members of the National-Liberal and National-Peasant parties, current members of minority religious denominations (called in the communist newspeak sectanți, members of a sect). The first appendix reflects the very diverse background of those who endorsed the Goma Movement. The largest group was that of workers (and not of intellectuals), which amounted to 102 persons out of a total of 430. Accordingly, those with a low level of education constituted the majority (235 out of 430). Ethnic Romanians were obviously the most numerous group, but proportionally Germans were overrepresented. Not surprisingly, the largest age group was that between 25 and 45 years (262 out of 430). Taking into account the categories of enemies defined by the Securitate, former political prisoners and members of pre-communist parties were surprisingly only a small minority among Goma’s supporters, with 26 having been convicted for crimes against state security and 11 former members of the democratic historical parties. Finally, the data show that almost half (171 out of 430) were residents of Bucharest, which is hardly surprising given the extra effort required from a person living in the provinces to contact Goma (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, 82).

The second appendix refers to the same categories and includes statistics regarding the percentage of people who were allowed to emigrate out of the total of persons who contacted Goma. Interestingly enough, the statistics are arranged by ethnic origin. Out of the total of 430 persons, 337 were Romanians, 71 Germans, 16 Hungarians and 6 of other ethnic origins. It is worth mentioning that Germans were proportionally overrepresented in this group analysed by the Securitate, given that this community constituted only around 1.6% of the total population of Romania, (360,000 Germans out of a total of 21,560,000 citizens of the Socialist Republic of Romania), according to the census of 1977. On the other hand, Hungarians were under-represented, given that this community accounted for around 5.8% of the total population (1,715,000 out of 21,560,000) in the same census of 1977. This apparent anomaly can be explained by taking into consideration, on the one hand, the prospects of fast and complete integration in the Western destination country of emigration, which the Federal Republic of Germany represented for Germans living in communist Romania. On the other hand, the Hungarians must have refrained in 1977 from joining a movement initiated from within the Romanian majority, as practically no record of collaboration between dissidents in these two communities in the Socialist Republic of Romania exists. Finally, it is worth noting the reaction of the Securitate, which preferred to let these individuals leave the country: by 1 April 1977, around 40% of the Romanians (137 out of 337) and of the Germans (29 out of 71) were granted exit visas, while all 16 Hungarians were allowed to emigrate (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/7, 83).

Data about these persons connected to the Goma movement were later updated in various notes of the Securitate, but these expressed in written form what this chart tried to accomplish in an easier-to-grasp graphic form. It is not clear why this type of chart was not updated as such. It might be inferred that there was no further need, because the movement practically ended its ephemeral existence with Goma’s arrest on 1 April 1977, which is also the day this chart is dated. As the chart indicates, most individuals who joined this movement against the violation of human rights in Romania were interested in the observance of one single right: freedom of movement or, in other words, the right to emigrate. Moreover, the statistics in the appendixes suggests that the Securitate was rather willing to grant a passport for emigration to the troublesome individuals, and eventually they did the same for Paul Goma and his family. Thus, this human rights movement which took inspiration from the Czechoslovak Charter 77 had, unlike its model, only an ephemeral existence as it practically ended after the arrest of the main proponent, Paul Goma.

Regarding the documents compiled by the secret police on Goma, it must be added that after his arrest, the Securitate opened a penal file against his name, which contains documents related to the arrest such as search reports, warrants, testimonies and interrogation reports. Goma was, however, released on 6 May 1977, after a rather short detention, due to massive protests by the Romanian emigration in Paris, which managed to convince many outstanding personalities to sign a petition for his release. Goma left Romania never to return just a few months later, in November 1977, thus ending his career as a dissident in Romania and opening a new one as a defender of human rights in exile. The plan discussed above remains witness to the vision the Securitate had of the Romanian collective protest for human rights. As Goma was the main person able to send messages to Radio Free Europe about this protest, the secret police took it for the creation of a single individual, who was anyway on the list of “usual suspects” as a “person with previous offences,” to use the working categories of the secret police. Thus, the best method of counteraction was the removal of this person. As noted in the report of 10 December 1986, which recommended the closing of Goma’s file of informative surveillance, “Paul Goma’s hostile action from the Spring of 1977 had no followers in intellectual milieus, but only among some dissatisfied and anarchic elements” (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, File I 2217/14, f. 254). To conclude, the collected data allowed a realistic evaluation of the Romanians’ perception of an issue alien to local political traditions, such as human rights. While the Western audience understood this movement as an attempt at monitoring violations of human rights, in a very similar manner to the one launched by Charter 77, hundreds of Romanian citizens seized the moment to endorse a single right: the right to emigrate. On the one hand, the desire to emigrate prompted a quick response on the part of numerous individuals, who joined the movement and thus contributed to its enlargement. On the other hand, the same desire to emigrate enabled the Securitate to quickly dissolve this ephemeral protest for the observance of human rights in communist Romania by simply granting a passport to those wishing to leave the country. True, the secret police managed to dissolve this collective action before it had the chance to establish itself as a genuine movement. This, however, was not a proof of the high efficiency of the Securitate, but of the way those who joined the movement (mis)understood their common goal. In short, the Goma Movement epitomised Romanians’ anti-communism by “exit” and not by “voice.” However, the Goma Movement constituted a collective action of protest without precedent in communist Romania, and remained until 1989 the anti-regime action with the widest support among the citizens of this country.